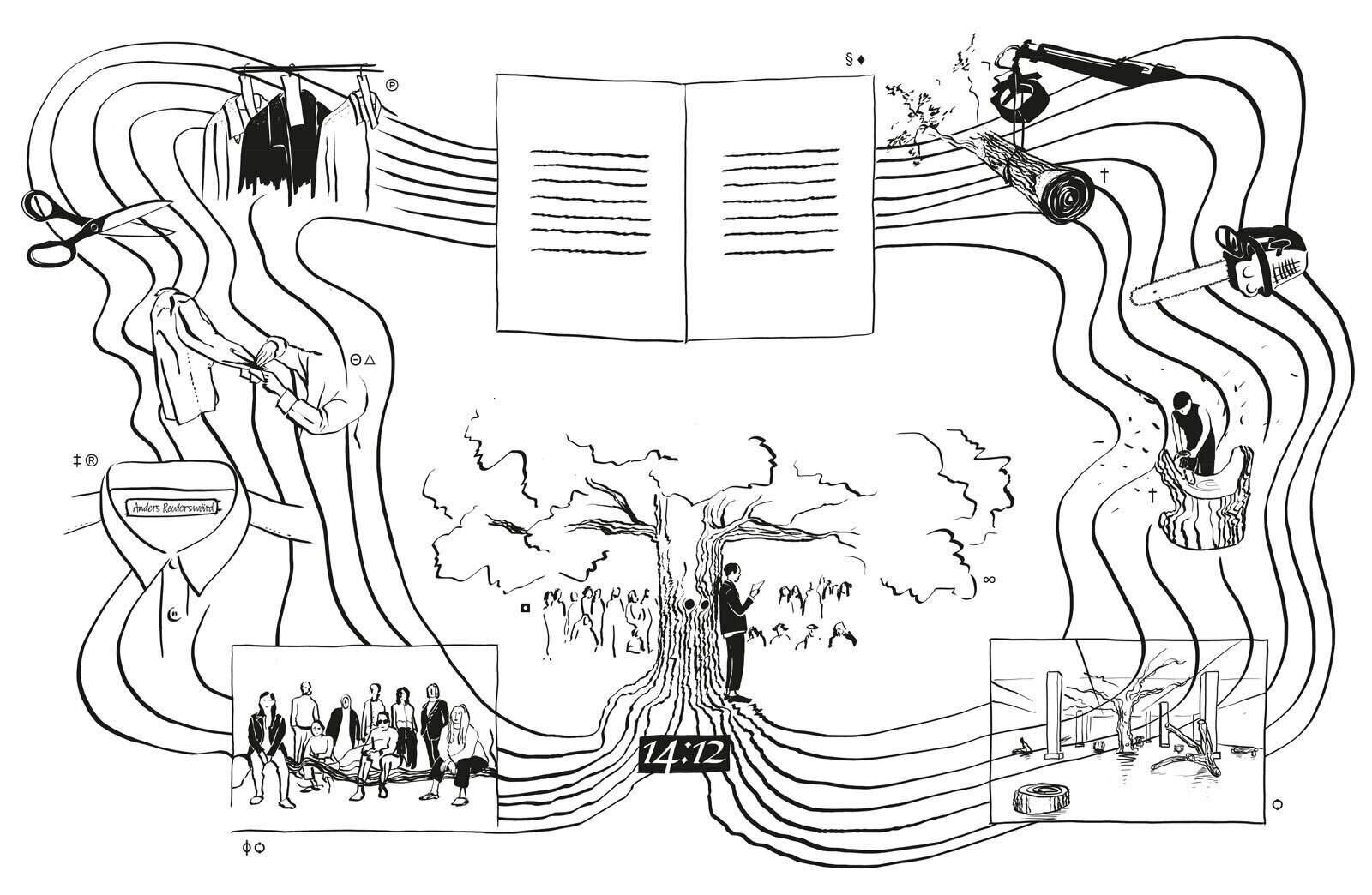

The breadth of the topic necessitated the physical expansion of the exhibition outside the Museum’s main exhibition spaces. The Fabric of Felicity starts in the Museum’s cloakroom with a special commission by Bella Rune. Following a research trip to Ivanovo, the center of early Soviet propaganda textiles, the artist used augmented reality to develop an app that activates a virtual unfolding of endless ornamentation. The exhibition also extends to Garage Bookshop. Swedish artist and theater director Marie-Louise Ekman created a limited edition series of men’s shirts with original drawings that reproduce, in the comic book manner Ekman is known for, a person’s biography through important everyday objects.

The Fabric of Felicity is the result of a thought experiment. What happens when we erase fashion from the conversation between garments and art? What kind of questions arise when there is no common ground where art and clothes habitually meet? The exhibition is based on an understanding of clothes as an offline avatar. In many ways, the choice of avatar is beyond the wearer’s control. Through the act of dressing humans are connected to industries that dictate style and behavior and depend on resources used in the creation of garments. Several layers of economic and political histories are activated by the simple act of putting something on. The philosophical foundation of this experiment can be found in German sociologist Georg Simmel’s classic essay “On Fashion” (1905). He outlines two types of existence for garments: one is based on equality and tends to operate in societies close to communism or during traditional ceremonies such as those associated with mourning; the other provides a feeling and a look of unity for different social strata. Simmel likens unity to a painting’s frame: it marks the internal coherence of a group and creates borders that exclude the Other. Both equality and unity in dress rarely exist as such, but a good example of their confluence is uniform, a subject of many works in the exhibition. Uniform marks those who wear it as representatives of certain traditional institutions (medical personnel, the military, etc.) and creates clanship when those in uniform position themselves close to sources of power.

The exhibition’s title is taken from Jeremiah Bentham’s An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1780). Bentham’s utilitarian philosophy proposed the shortest and most rational route to cure society’s ills as being to subjugate pleasure and pain to power. He posited the principle of utility that produces what he called “the fabric of felicity by the hands of reason and of law,” “felicity” in this case being the level of happiness of a given society. “Fabric” and textile work in general have been used as metaphors for social life at least since Plato, and in this exhibition the physical part of dress is always considered alongside its social meaning. Uniforms, for example, are generally considered to be utilitarian and anonymous, and some avant-garde projects of the 1920s equated utility and felicity. In contrast, non-professional clothing is widely regarded as a symbolic act of self-expression.

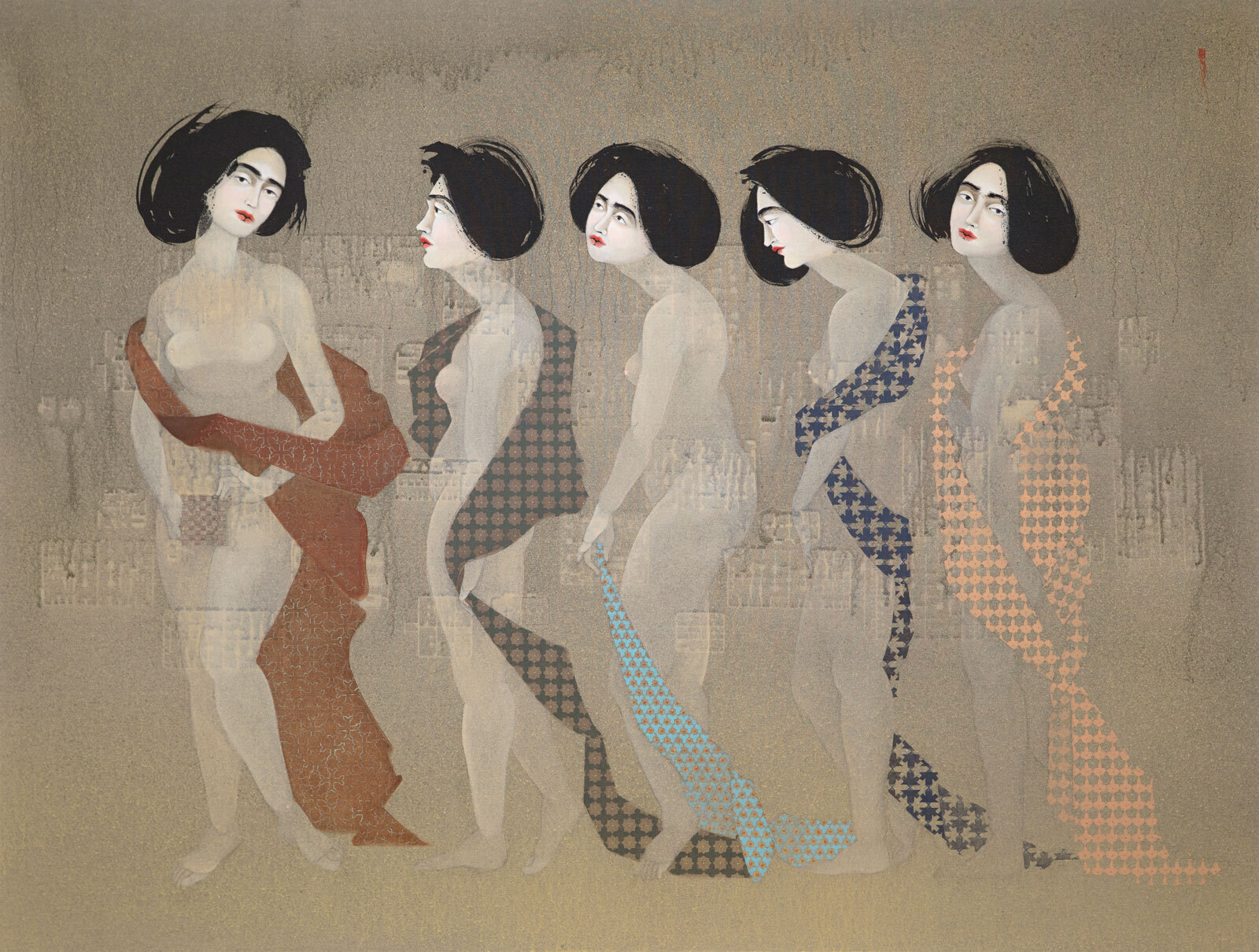

Organized by Garage curators Valentin Diaconov, Ekaterina Lazareva, and Iaroslav Volovod, The Fabric of Felicity aims to uncover variations and paradoxes within the dichotomies of anonymity and personality, work clothes, and personal dress. One work that arguably epitomizes these conflicts is Triumph of Fragility (2007) by Russia’s feminist duo Factory of Found Clothes (Olga Egorova and Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya). The largest section of the exhibition looks at clothing as a metaphor for mass movements and the victims of mass migration. An installation by Bangladeshi artist Kamruzzaman Shadhin, made with second-hand clothes collected from refugees, including Rohingya people, is exhibited alongside Vladislav Shapovalov’s documentary realism. Sharon Kivland’s installation investigates and allegorizes the dress codes of the French revolution. Yuichiro Tamura presents his collection of baseball jackets with traditional Japanese embroidery, commissioned by American military during the Korean war (1950–1953). Another section of the show is dedicated to “chthonic fashion” and showcases artists that use textile and clothes as a medium to address the wisdom of previous (often premodern) generations. Hamid El-Kanbouhi and Hayv Kahraman retrace their identities on the frontlines of social and political unrest in a globalized world. “Naked costume”—nudity as an expression of vestimentary codes—is the main concern of a small section that compares work by Soviet conceptual artists Rimma and Valeriy Gerlovin, documentary photography by Pedro Valtierra, and highly stylized shots by Jimmy DeSana. The exhibition also includes an archival section that tells the story of avant-garde experiments with total uniform and connects them to the notion of universal form in postwar abstraction.

Curated by Valentin Diaconov, Ekaterina Lazareva, and Iaroslav Volovod, Garage curators.