You wanna party? You got it!

You can listen to the podcast on SoundCloud, Apple Podcast or Yandex.Music.

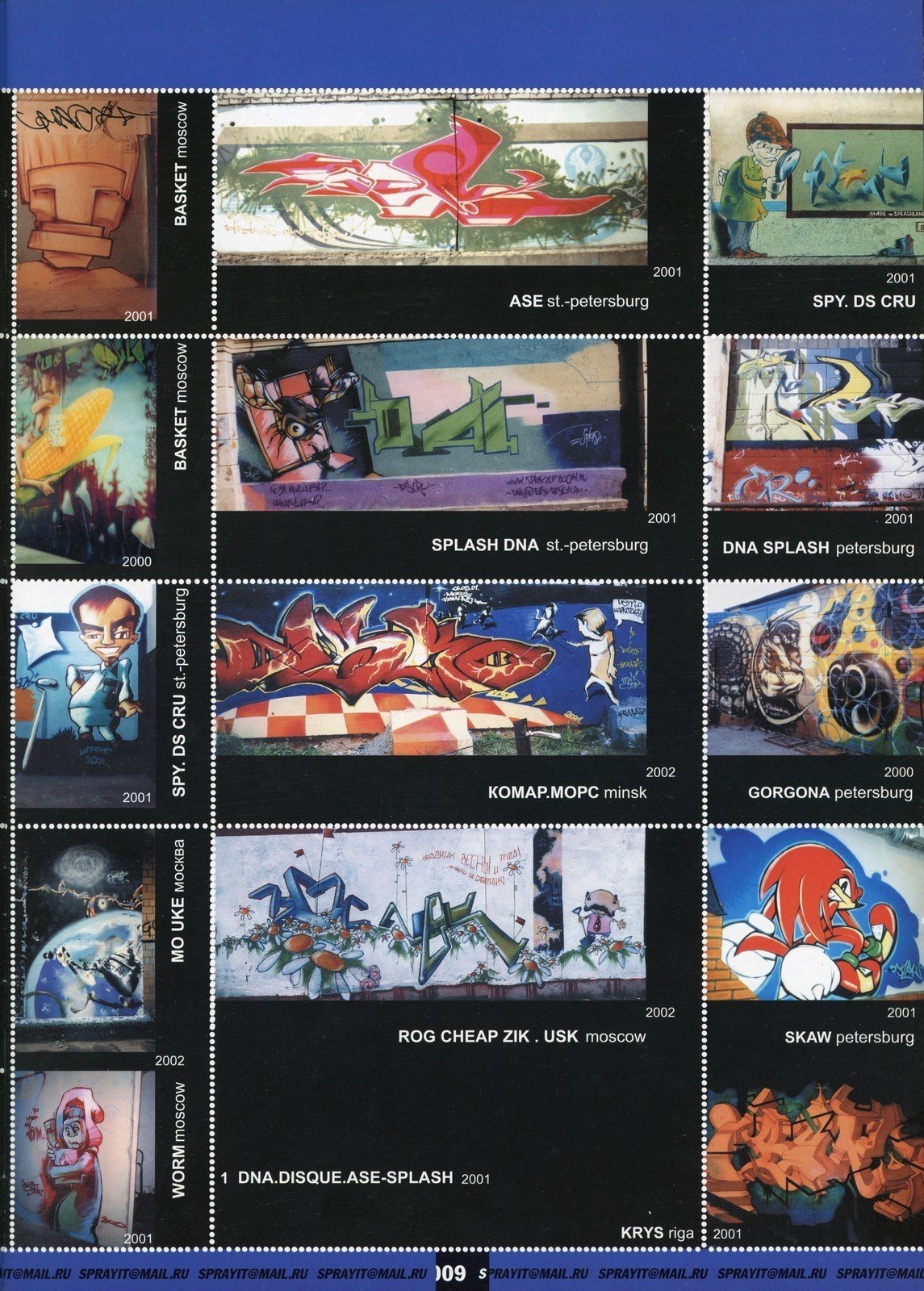

According to the participants, the history of Russian graffiti is divided into three periods, or waves. The first wave took place in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the first graffiti artists appeared in the USSR. The second wave, marked by the formation of graffiti and its spread, covers most of the 1990s and was connected to the fact that new information sources about graffiti and its popularization appeared thanks to interest in street culture. The beginning of the third wave in 1998–1999 was marked by a boom in graffiti, with various festivals across the country, an exponential increase in the number of artists, and the appearance of graffiti magazines and websites.

In the first half of the 1990s, when, after a break caused by political and economic chaos the second wave of Russian graffiti began, on the streets of St. Petersburg there were only a few pictures and tags made by such artists as Max Navigator, Barmaley (Alexey Bogdanov), and Vadim “Krys” Meikshan. The unusual font compositions attracted attention. At that time only a few people had information about graffiti. Before the Iron Curtain fell, it seeped through only in rare magazines, music videos, and documentaries about hip-hop culture and breakdancing. In post-Soviet Russia, hip-hop became popular closer to the middle of the 1990s, when the Hip-Hop Culture Center1, opened in Moscow, and magazines and audio cassettes of Western artists appeared on sale. On the central squares of St. Petersburg one could often see B-boys breakdancing, and hip-hop fans gathered at Gorkovskaya metro station. Second-wave graffiti writers also hung out there: Denis, Taras, and Vadim from the first St. Petersburg graffiti group, SPP Crew.

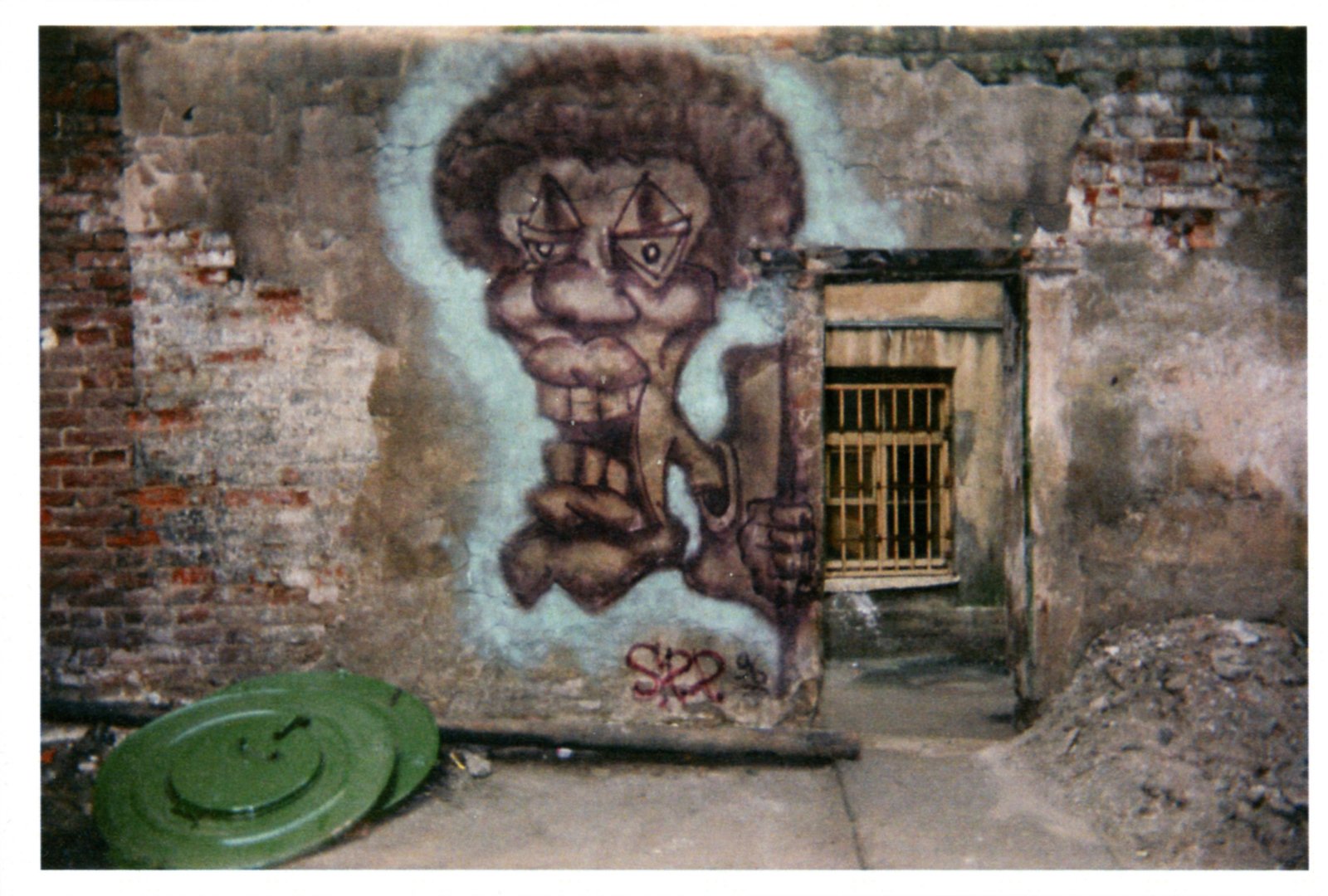

The team, whose name stands for St. Petersburg Patriots, was founded in 1995. Influences include the 1984 book Subway Art—an international bestseller written by photographers Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant about New York graffiti—and a special issue of the American magazine Rap Pages. Inspired by Western writers, SPP began actively exploring the urban space and the first graffiti locations appeared in St. Petersburg: a wall on Kremenchugskaya Street and “the line” along the railway tracks of the Moscow railway station, plus the Hall of Fame in the city center. The Hall of Fame is a location where graffiti artists can write without the risk of being caught by the police or vigilant citizens, thanks to which local and visiting writers come there to work. The first Hall of Fame in St. Petersburg was the yard at 61 Liteiny Avenue, where SPP Crew have been regularly created new works since 1996.

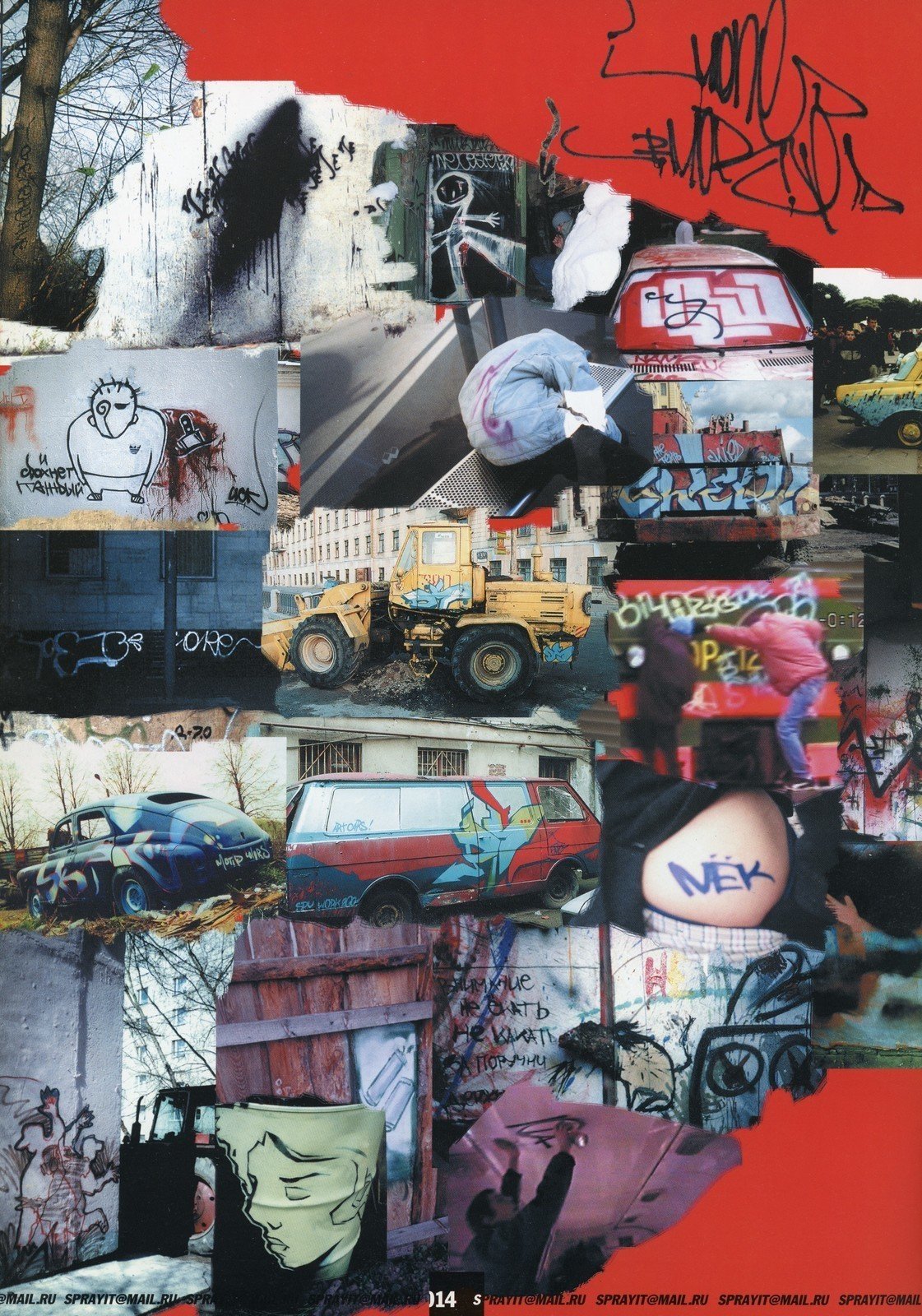

In 1997, SPP opened the Tribe Hip-Hop Boutique in the Renegade store, located at 50 Fontanka Street. This was the first graffiti shop in St. Petersburg, where you could buy professional spray paint2, tagging markers and thematic magazines. In the same year, artists held a graffiti jam at Renegade, a report about which was broadcast on DJ and artist Vikenty Dav’s TV program Demo. More and more people were interested in the new subculture and SPP became frequent guests on radio and TV, participating in the video program Reeds and interviews on PORT FM and Record Youth radio stations. Graffiti captured the city, becoming a youth culture marker. SPP decorated the entrance to the Griboedov Club and painted a temporary wall near the Saigon Café and shop windows of clothing stores for ravers and fans of street culture. Graffiti became more popular thanks to rap musicians. The band Bad Balance band, of which Oleg Basket was a member, made clips and organized hip-hop festivals with the graffiti jams. The video You wanna party? by Da Boogie Crew featured on Russian MTV and was an instant hit. Hip-hop culture and graffiti could be found at large-scale events in the city: the Festival Against Drugs on Manezhnaya Square (1998), the Flash 98 music event organized by Radio Record, and the festival Spin in Our Way (1999) held on Palace Square.

Such activity bore fruit. By the late 1990s, in addition to SPP and a number of first-wave artists, four graffiti teams were writing regularly in the city— FGS, SAE, and DS—plus Berlin artist Katya Zwei, writers Vova Zaaf (a.k.a. Skleroz), FUZE, Nitro, Occultra, Splash, Stas Bugs, and others. Summer 1999, a united team of writers from Moscow and St. Petersburg, got into metro tunnels for the first time, opening the era of metro-bombing.

During the 1990s, St. Petersburg street cleaning services did not bother much with graffiti, so some drawings existed for several years, becoming points of attraction for future generations of artists. The city center and the surrounding area were in disrepair, so bright drawings and English-language inscriptions seemed like the spirit of the time, of the new Western culture that was appearing in post-Soviet everyday life. The words emerging on city walls—Fight the power, Discophile, Break, East, Anger—seemed to be the voice of a new generation that grew up during a serious crisis and the subsequent building of new identities.

1. The Hip-Hop Culture Center opened in 1994. St. Petersburg first-wave graffiti artist Oleg Basket was one of the organizers.

2. European spray paint brands such as Montana and Motip appeared in the city in the second half of the 1990s. Before that graffiti writers mainly used car enamel.