In Memory of Poor Lisa

You can listen to the podcast on SoundCloud, Apple Podcast or Yandex.Music.

You can listen to the podcast on SoundCloud, Apple Podcast or Yandex.Music.

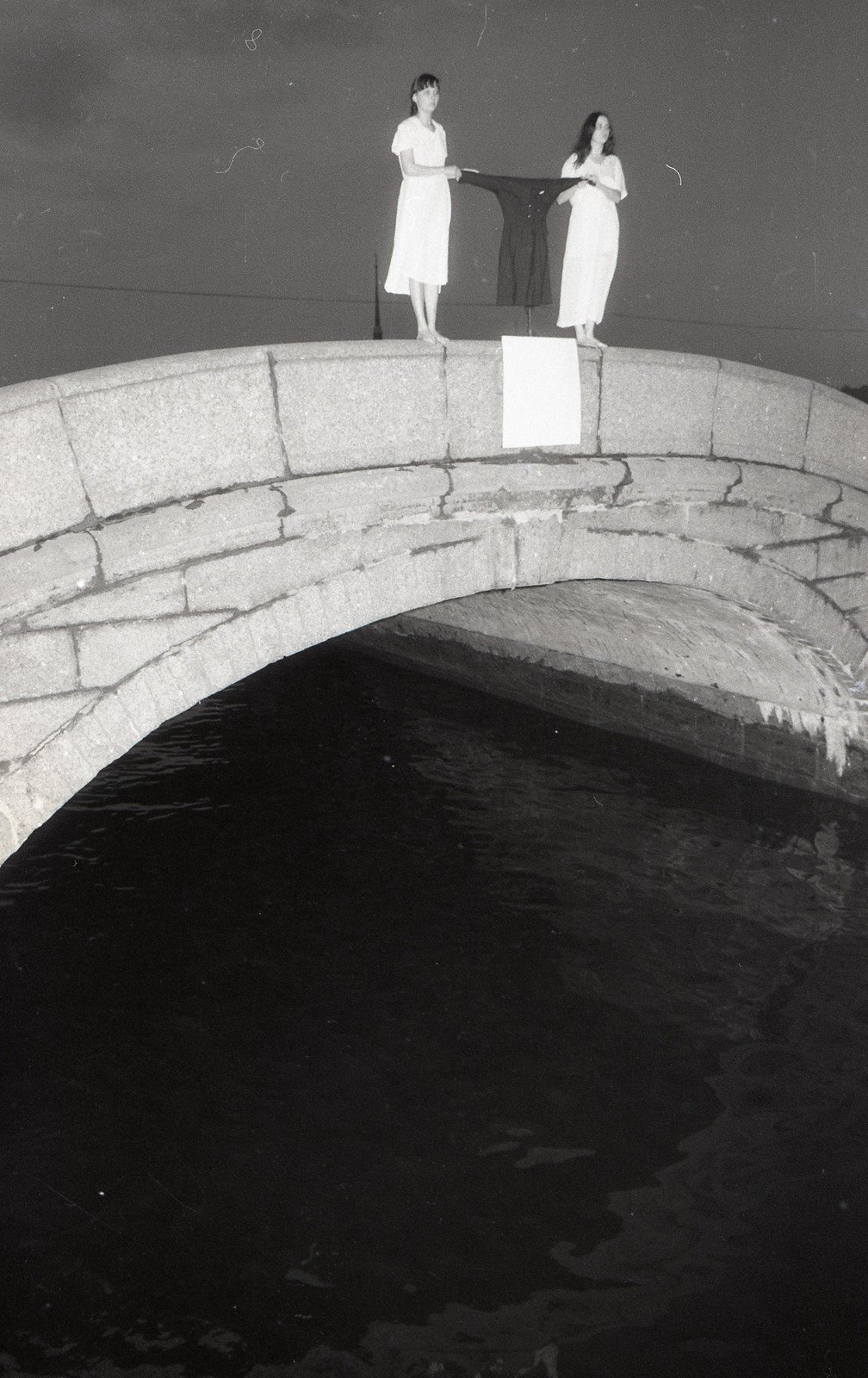

At midnight on June 20, 1996, the silence of a clear summer night was broken by a splash. Two girls in white clothes, clutching a black dress in their hands, had jumped from a bridge into the Winter Canal. This strange, fascinating action was witnessed by a small number of passers-by and a few spectators invited to the performance by the group Factory of Found Clothing.

Factory of Found Clothing (FFC) is a joint project by two St. Petersburg artists, Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya (Glyuklya) and Olga Egorova (Tsaplya). The creative duowas formed in 1995. The name came from the participants’ focus on clothing, which they considered a tool for exploring issues of physicality and personal and social relationships between people. From the moment it was formed, one of the group’s main mediums was performance. According to the artists, this was connected to the general mood in the artistic environment of the second half of the1990s, when the border between art and life was as blurry as possible and “art was created by presence,” 1, turning everyday life into an endless performance.

The action, dedicated to everyone “who knows the torments of love,” was called In Memory of Poor Liza. Today it is one of the most famous early works by FFC, with which the artists often begin to tell the story of the group. The title of the action refers to the story of the same name by the Russian writer Nikolai Karamzin. In the 1990s, the artists explored the symbolism of unhappy love, this romantic feeling full of passion and madness, as a part of the myth of the female world. However, the FFC participants, in expressing sympathy for poor Liza, offer their own scenario for living through a love drama. In an interview with curator Victor Misiano, Glyuklya discussed FFC’s intention to refute existing cliches about the weakness of female nature2. Playing along with society, the artists put on white dresses and jumped into the canal, depicting victims. Unlike poor Liza, they then got out of the water and after this “all of the most interesting things began happening”.

The jump made during the action refers to the theme of the Feat, one of the key concepts in the mythology of FFC and in the world of the High School Student, a lyrical character created by Glyuklya and Tsaplya in the mid-1990s. The image of the High School Student contains “the historical character that existed in St. Petersburg in the pre-revolutionary period”3 and she embodies the most strange, capricious, and contradictory part of the soul, where fatal passions are replaced by tenderness and timidity, because she loves to embroider with beads, and “the blue steel of the barrel of a revolver.”4. The artists are sure that the High School Student lives within every person and the recognition of this part of oneself can become a source of freedom and joy necessary for creation in the name of “A Beautiful Dream that overcomes Death.” In the action on the Winter Canal, the victory of Love is confirmed by the miraculous rescue of the girls, who got out of the water unharmed. And the black dress, symbolizing death, floated away into the unknown.

FFC began to work with clothes, or, as the artists put it, “the dress” from the moment the group was founded. Glyuklya graduated as a textile artist from the Mukhina School (now the Stieglitz St. Petersburg State Academy of Art and Design), and Tsaplya created the Traveling Things Store, remaking second-hand clothes by supplementing them with strange details and giving them their own voice, which sounded through phrases embroidered or written on the fabric. This was consonant with the general poverty of the1990s, when most residents of St. Petersburg dressed from second-hand stores and were forced to romanticize the unconventionality of such outfits and the “aura of the previous owners.” FFC clothes tell us about their owners, creating them based on a certain image. The recognition of the power of clothing in the creation of an image echoes the “culture of dressing up”5 and dandyism, used in St. Petersburg in the 1990’s thanks to the artists of the New Academy of Fine Arts circle. However, unlike classical dandyism, where clothes create a facade of personality, “the dresses” of the FFC become an alter ego of a person, exposing his or her secrets and weaknesses.

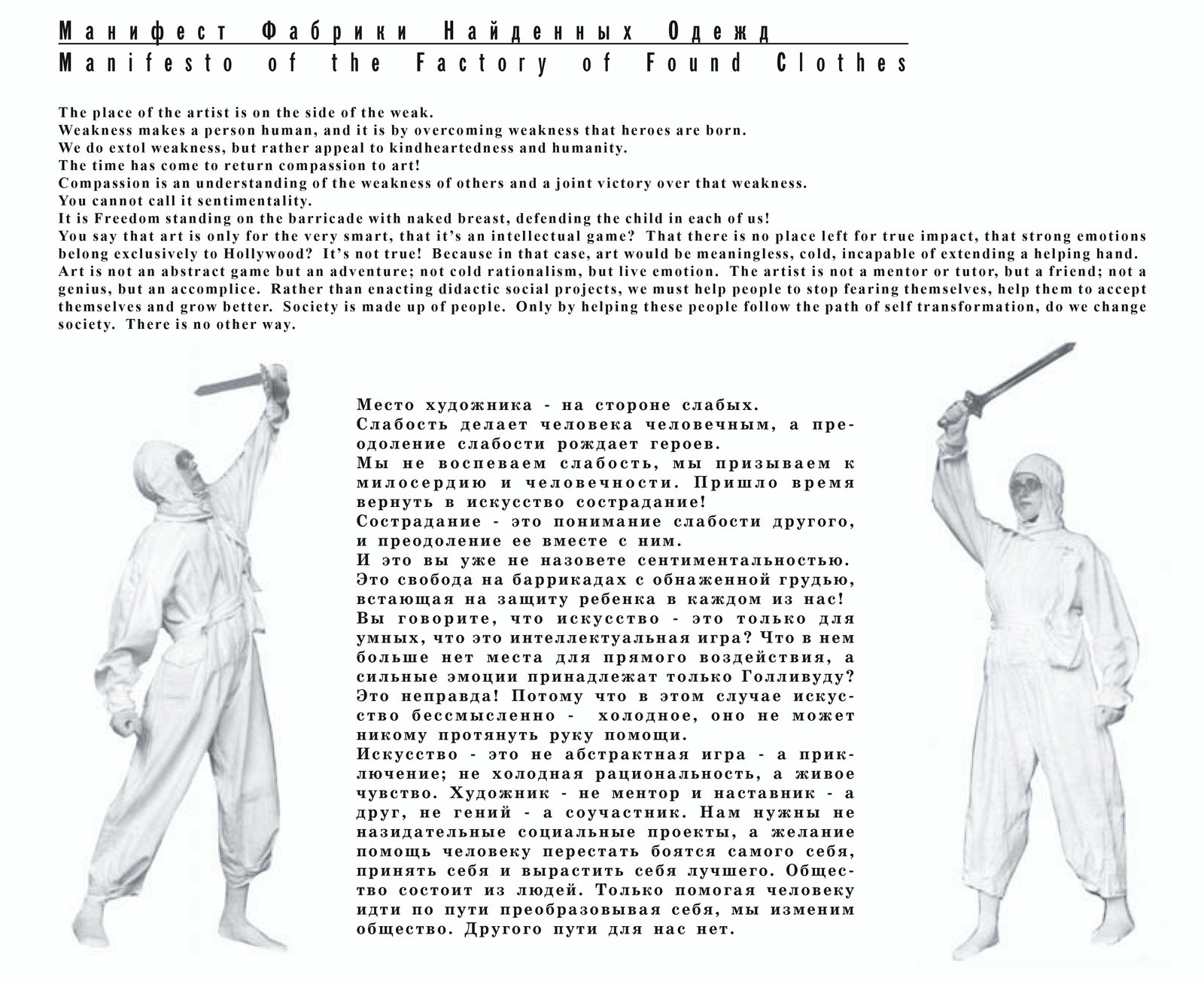

At the beginning of the 2000s, the sublime High School Student, depicted in FFC performances as a simple white dress, was replaced by “the whites,” fictional creatures depicted by Gluklya and Tsaplya dressed in depersonalizing chemical protection suits. The ideas of exalted feelings, the feat, and the beautiful dream were replaced by the concept of social performance that could have a healing effect on society. FFC projects took the form of a direct interaction with the viewer, based on participation and the desire to share the experiences. This position is presented in the manifesto entitled “The Artist’s Place is on the Side of the Weak,” which was published in the first issue of the Chto delat? newspaper in 2003. The manifesto contains the following lines: “Art is not an abstract game but an adventure; not cold rationality but a living feeling. An artist is not a mentor but a friend, not a genius but an accomplice.”6.

However, in appearing on the streets of different cities and violating the usual order of things with their presence, “the whites” retain a part of the High School Student by revealing the lack of childlike spontaneity in the modern world.

In 2010, a reenactment of the performance In Memory of Poor Liza took place in Amsterdam, with Glyuklya and art historian Pieter Wagemakers taking part.

1. Factory of Found Clothes, FNO. Utopicheskie soiuzi (Мoscow: Moscow Museum of Modern Art, 2013), p. 29.

2. Ibid.

3. “Gimnasistki v poiskakh podviga,” Ptyuch, 2, 1998, p. 70.

4. Ibid.

5. A. Artyuk, “Glyuklia i Tsaplia: ‘Preodolevat’ strakh — eto my liubim!’,” Iskusstvo kino, https://old.kinoart.ru/archive/2008/08/n8-article21

6. “Manifest Fabriki Naidennykh Odezhd,” Chto delat?, 1, 2013, p. 13.