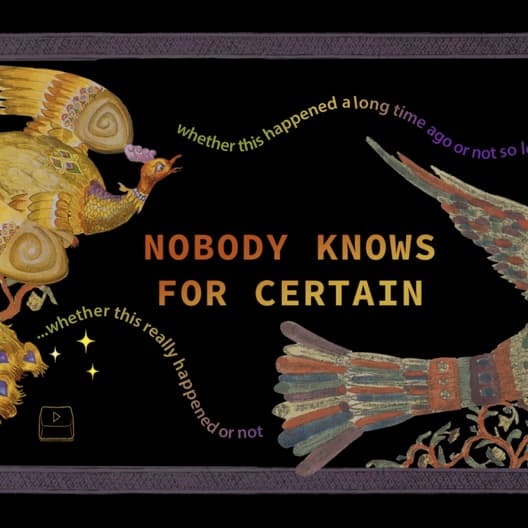

«Whether this happened long ago, or not so long ago,

whether this really happened or not, nobody knows for certain.»

The Magic Flute (Belarusian folk tale)

The starting point for Afrah Shafiq’s project was the popularity of Soviet children’s books in India from the 1960s to the 1980s.

During the Cold War, India and the Soviet Union maintained cordial relations, with a dedicated focus on cultural exchange. Russian ballet and circuses performed in Indian cities and were broadcast frequently on Indian state television. Sovietland magazine was published in thirteen Indian languages. One particularly delightful by-product of this strategic agreement was an abundance of richly illustrated Soviet children’s books that were easily available in big cities and small towns across India1.

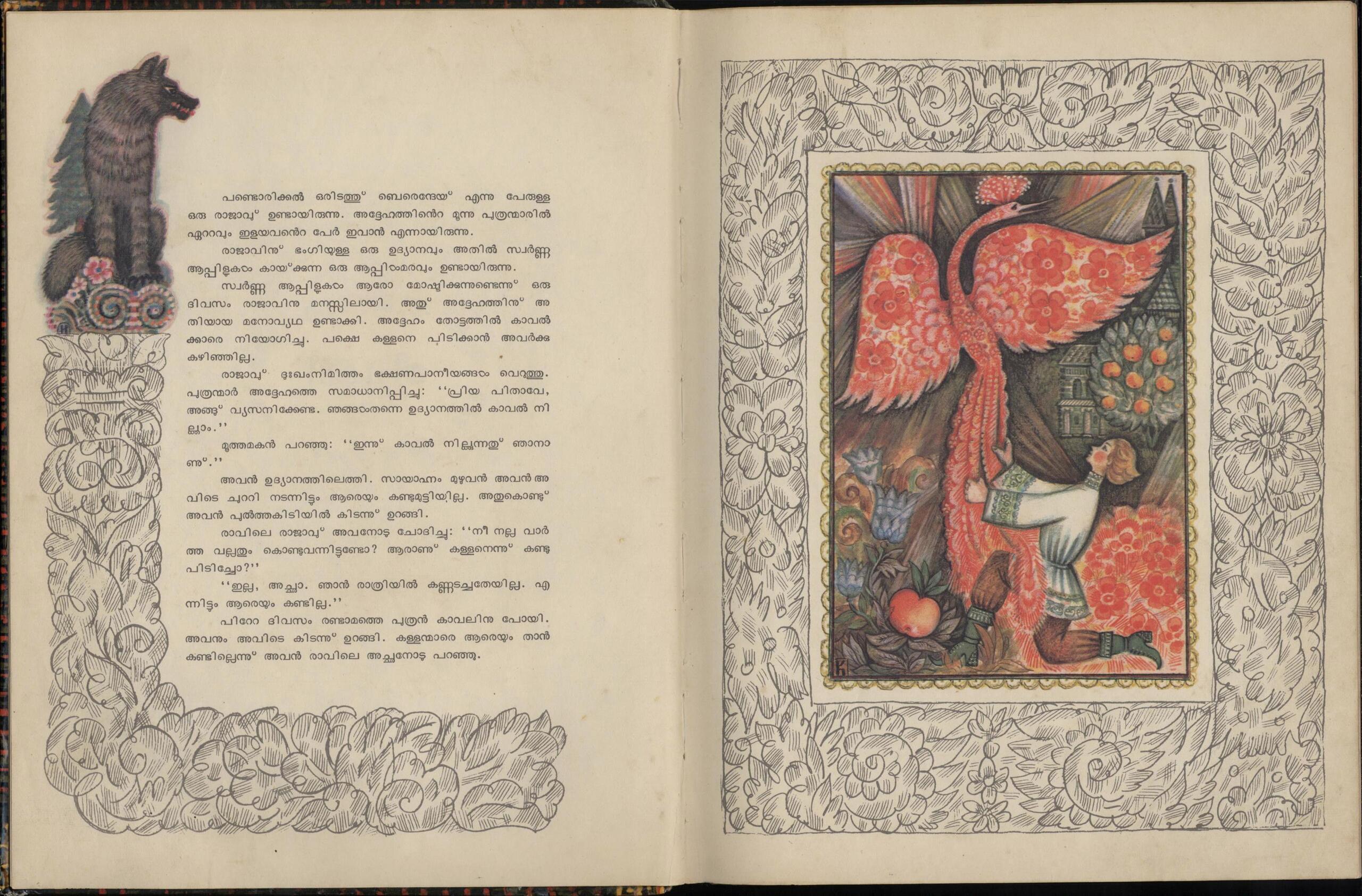

In Moscow there were two main publishing houses (Progress Publishers and Raduga Publishers, both now defunct) that produced these books for the Indian market. They were translated into English and most other major Indian languages and distributed in India at incredibly low prices. The outreach in India took place through a well-mapped distribution plan involving local book fairs, mobile vans, neighborhood stalls, and stocks at almost every railway station. In Kerala for instance, the circulation of Russian children’s books in Malayalam was organized by the Communist Party of India’s Prabhat Book House, which obtained the rights to import Russian books in 1952.

Soviet fairytales and stories form a significant part of the childhood memories of those who grew up from the 1960s to the mid-1980s. Today, in a number of South Asian countries there is a thriving subculture of collectors of these now out of print books, holding on to a nostalgia for their childhood and a deep affection for a nation that was never theirs and which no longer exists.

Against this backdrop and within the framework of Garage Field Research, Afrah aims to explore the world of children’s books from the Soviet era in order to talk about how stories are influenced by notions of the nation and how the act of storytelling can be playful and dangerous, a site of both control and subversion. She will dismantle the story through the archive, to study what it might reveal about the imagination of the nation state, the idea of utopia, and the place for fantasy in a world that was increasingly leaning toward industry and realism.

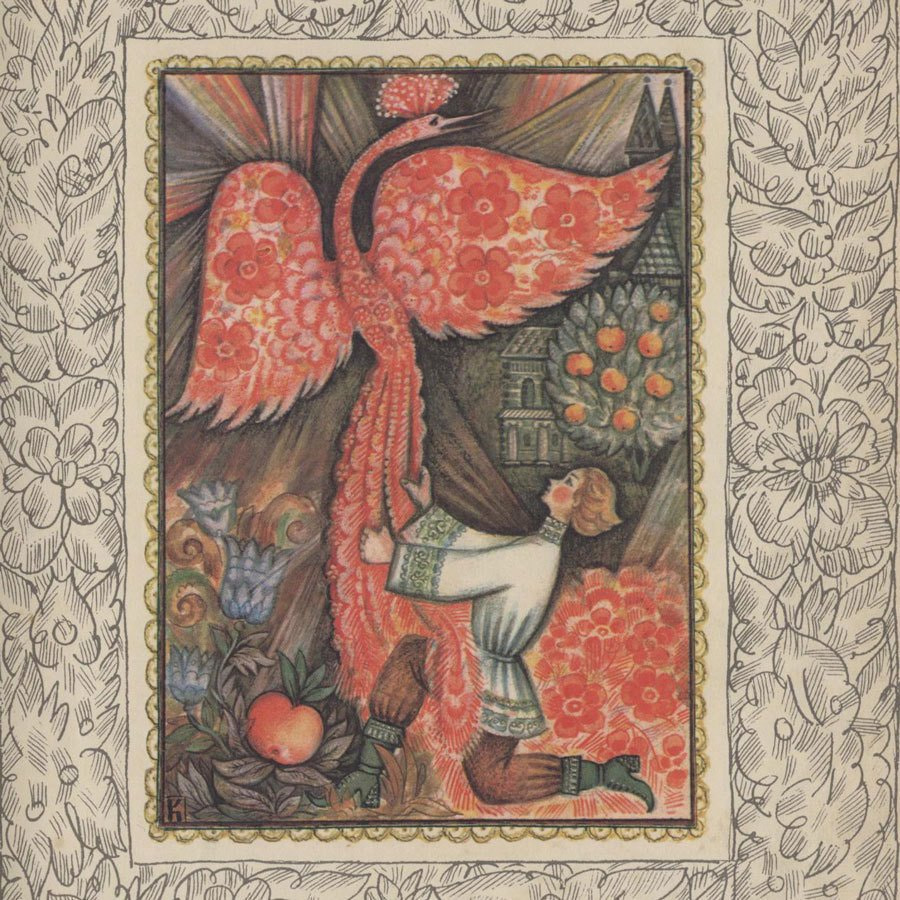

Afrah has observed that Soviet children’s stories and the accompanying illustrations reflect two different worlds that were straddled simultaneously. The world of the skazka, the fairy tale, featured illustrations drawing on a rich tradition of folk forms such as the lubok print, lacquer miniatures, the textile and decorative arts, and the Mir Isskustva (World of Art) and Art Nouveau movements. The children’s tales of Soviet writers, with their focus on space, industry, and the idea of a new nation and a new citizen, were influenced aesthetically by the avant-garde, geometric abstraction, constructivism, and suprematism.

The research finds its starting point in Vladimir Propp’s almost data-scientist-like analysis of the morphology of the folk tale, where «within the labyrinth of the tale’s multiformity, becomes apparent an amazing uniformity.» It will pay particular attention to the tropes of a distant land of possibilities—from Lukomorye to the Thrice-Nine Tsardom—the field of mushrooms as a site for seekers, the evolution of archetypes such as the Sirin bird, the older wise woman—from Baba Yaga to babushka—and the search for something that nobody knows for certain.

At the conclusion of her research, Afrah will create a new narrative work that infuses familiar characters, plot patterns, and worlds with newer philosophical and political dimensions. The form of the work will emerge as part of the research process.

1. Deepa Bhashti, «Growing Up with Classic Russian Literature in Rural South India, ” Literary Hub, February 28, 2018, https://lithub.com/growing-up-with-classic-russian-literature-in-rural-south-india/

Status: 2020–2023

Researcher: Afrah Shafiq