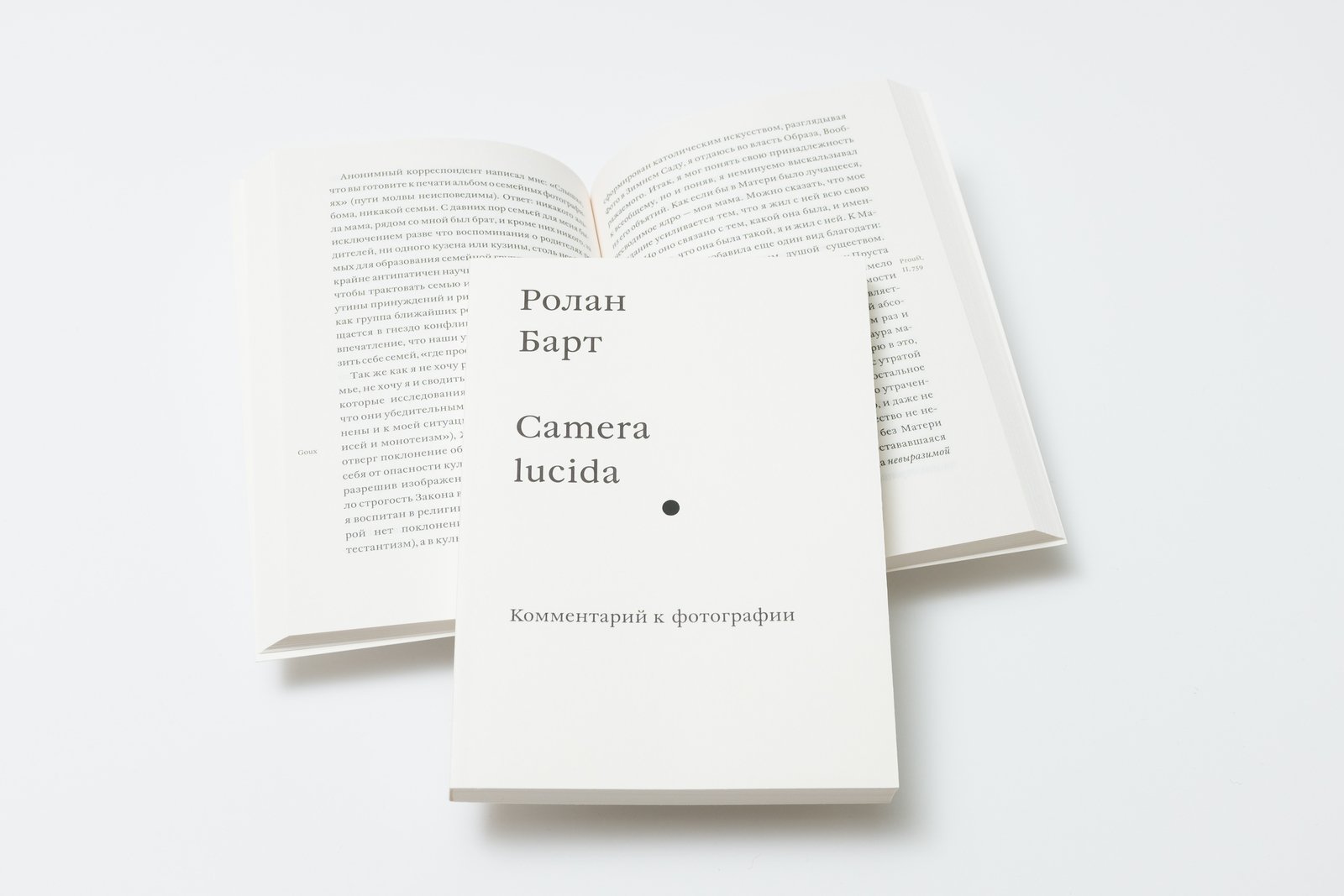

Roland Barthes’s essential study explores the nature of photography through the search for its special ‘genius’.

Although Roland Barthes often used photographic materials in his structuralist analyses of the bourgeois myths in mass culture and advertising, it was not until his last years that he published a collection of essays entirely devoted to photography. In Camera Lucida, the French philosopher moves away from the semiotics of binary oppositions and effectively envisages photography as a signifier without a signified. ‘Whatever it grants to vision and whatever its manner’, he writes, ‘a photograph is always invisible: it is not it that we see’. And ‘… the photograph is never distinguished from its referent’. According to Barthes, this ‘adherence’ of the referent makes it hard to formulate photography’s fundamental feature, ‘the universal, without which there would be no Photography’.

However, in the first part of the work Barthes devises a language that allows him to do so, introducing the concepts of the operator, the spectator and the spectrum. The spectrum, which is the referent in the photograph, comprises two elements: studium, or the cultural knowledge that allows the spectator to understand what is captured in the photograph, and punctum, which in Latin means ‘a wound, a mark left by a pointed instrument’ and which ‘breaks the studium’. These ‘stings’, ‘specks’ or random details in a photograph cut through the homogeneity of the studium and ‘prick’ the spectator, as Barthes puts it: some photos ‘prick’ him, while other don’t.

If they don’t, the reason might be the photographer’s intention becoming obvious to the spectator. ‘What I can name cannot really prick me’, Barthes explains. In this sense, punctum is the opposite of ‘surprises’: rare or shocking events captured by the camera, or special effects used by the photographer. Although the nature of punctum is elusive, most often it hides in some detail that catches the eye of the spectator. ‘Duane Michals has photographed Andy Warhol: a provocative portrait, since Warhol hides his face behind both hands. I have no desire to comment intellectually on this game of hide-and-seek (which belongs to the studium); since for me, Warhol hides nothing; he offers his hands to read, quite openly; and the punctum is not the gesture but the slightly repellent substance of those spatulate nails, at once soft and hard-edged’.

The second part of the book is more personal. Returning to his concept of photography as ‘pure contingency’ and an ‘emanation of the referent’, Barthes explains that he first thought of analyzing it after his mother’s death in 1977. Looking through her photographs, he discovered what he would later call punctum in a photo of her as child in a winter garden. ‘Something like an essence of the Photograph floated in this particular picture’, he explains. ‘I therefore decided to "derive" all Photography (its "nature") from the only photograph which assuredly existed for me, and to take it somehow as a guide for my last investigation’.