Japanese Laboratory J100R

About the participants

Lead researcher of the laboratory:

Viktor Belozerov (b. 1996, Moscow) has a Master’s degree in the theory and history of art and is a researcher and Japanese specialist. Graduated from the Art History Faculty of the Russian State University for the Humanities (Moscow). Created the educational project Gendai Eye, which aims to promote contemporary Japanese culture in Russia. Lives and works in Moscow.

Research group: Daria Bobrenko, Oxana Polyakova, Ksenia Sedyakina, Ivan Yarygin

Japanese Laboratory J100R focuses on ideas about contemporary Japanese art in Russia from the 1920s to the present.

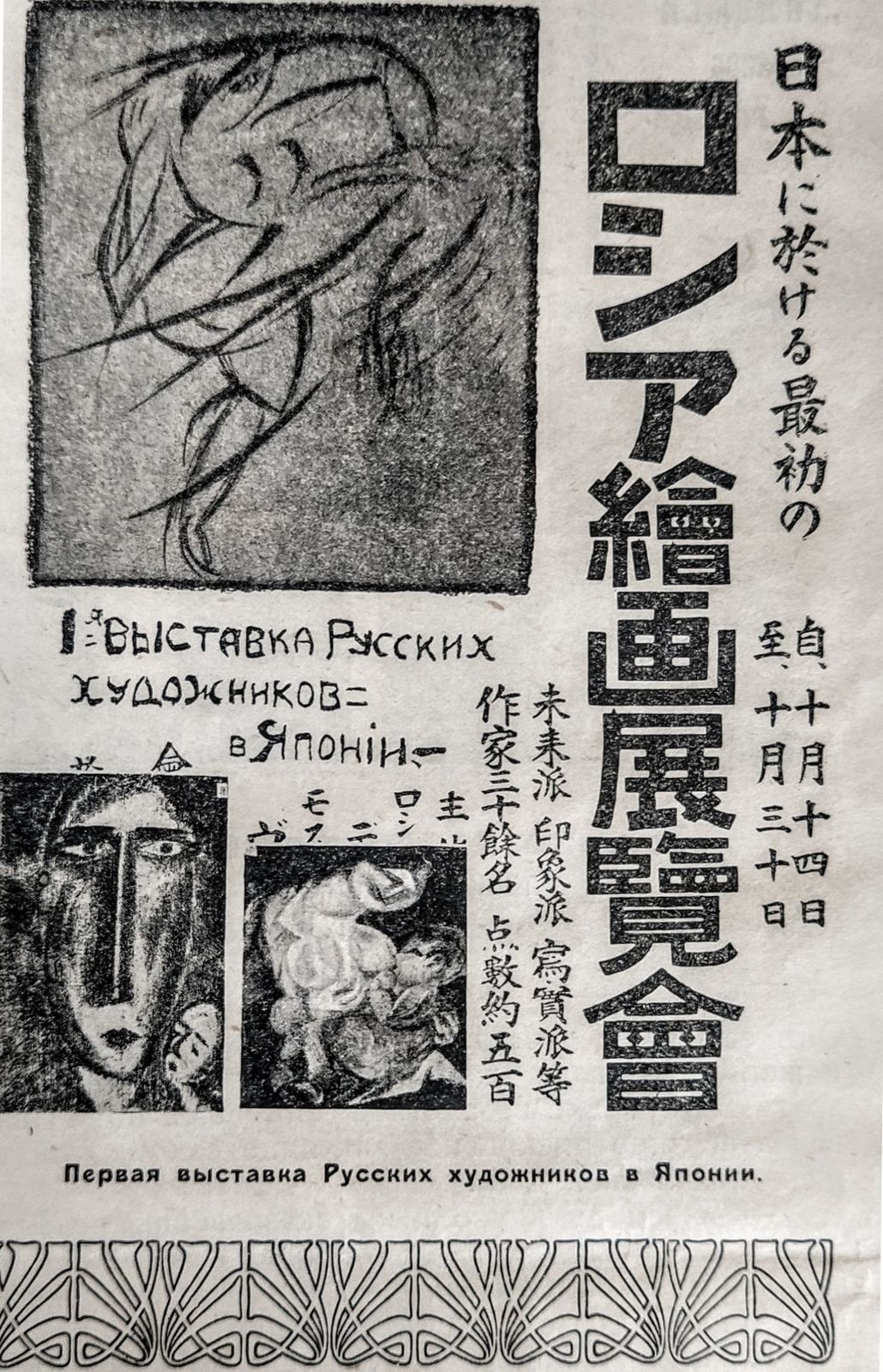

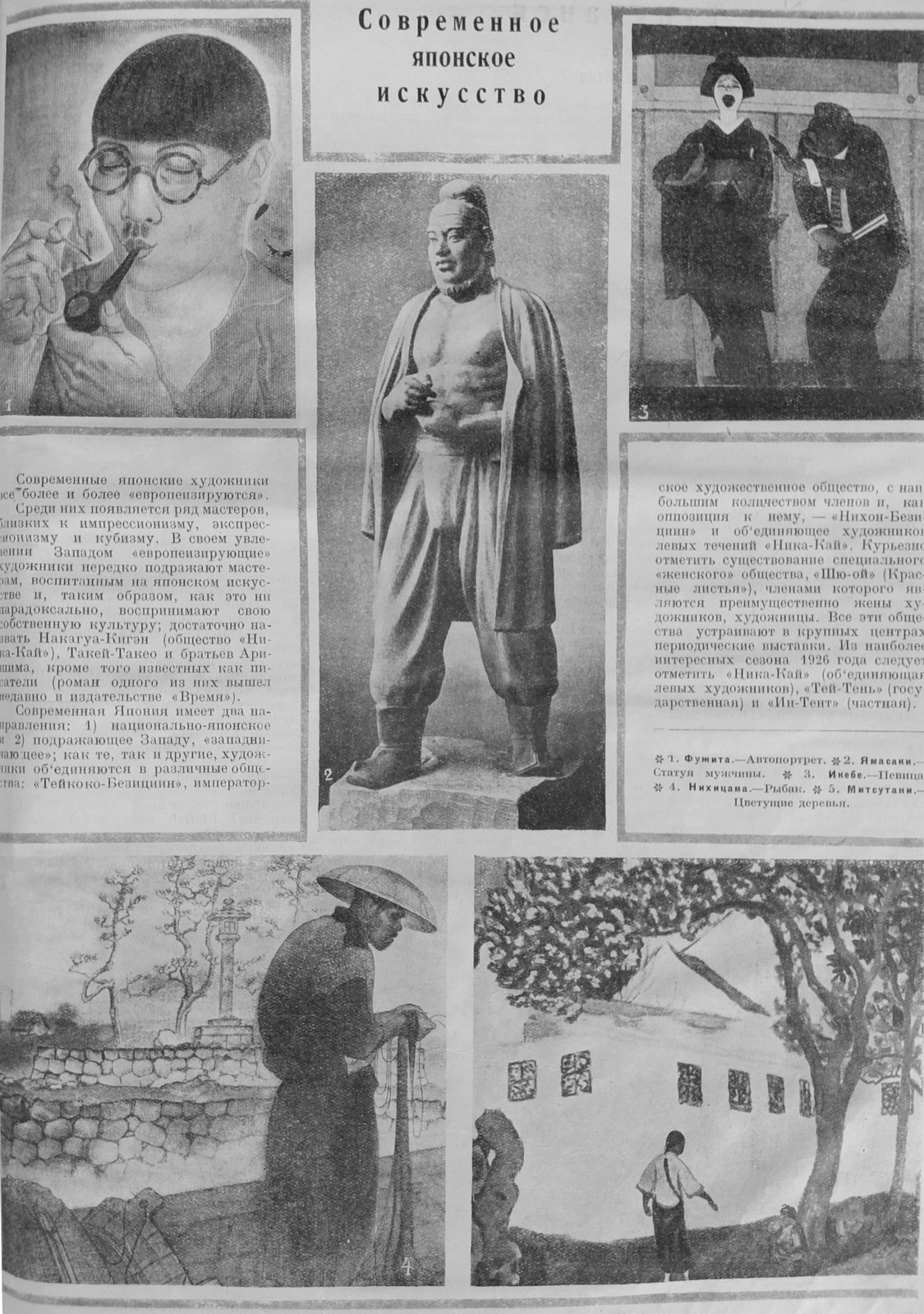

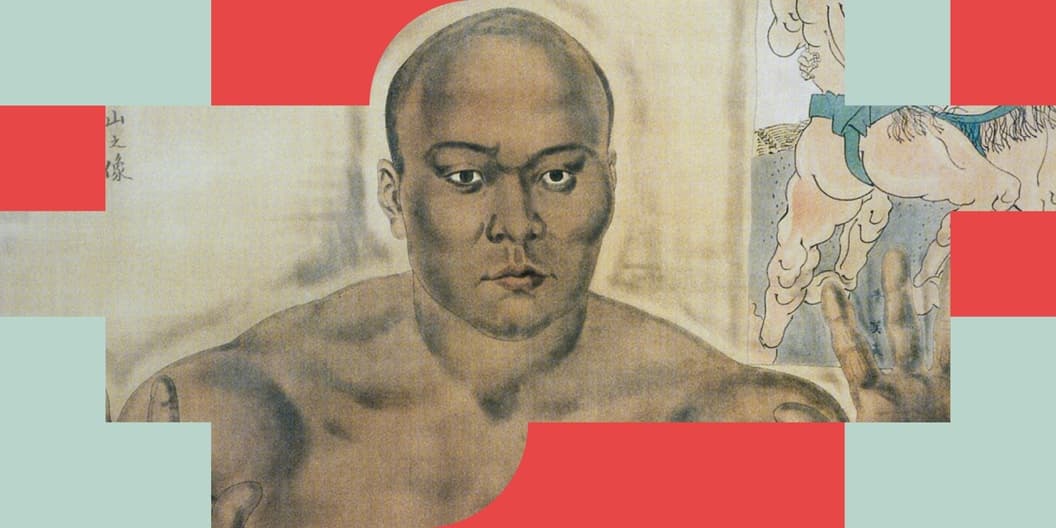

The obvious alignment of the chronology of events is difficult, but it is by no means the essence of the research, which prioritizes reflecting the complexity of interpretive processes and the formation of a holistic perception of twentieth-century Japanese art by both professional and mass audiences. From the 1920s, Soviet art history began building its own history of contemporary Japanese art, allowing certain names and prohibiting others. In the 1950s, the names of Iri and Toshi Maruki, “progressive artists and peace activists,” could be heard in the Soviet Union, but avant-garde groups such as Jikken-kobo or Gutai, who worked at the same time, remained completely unknown.

Since this ideological cordon sometimes failed, the work of “alien” artists, representatives of all sorts of “isms,” seeped into the pages of magazines as negative examples, but they made it possible to simultaneously emphasize the “mistakenness” of new Japanese artists’ turn to bourgeois art and the exceptional correctness of realist artists, so pleasing to Soviet ideology. Commitment to the same topics, rooted in social and political struggle, humanistic motives, and recognizable elements of national culture, made it impossible to present a general picture of contemporary Japanese art, ultimately (in the post-Soviet period) leading to a historiographical void. Attempts to show contemporary Japanese artists in Russia have not filled the gaps in research into the subject of twentieth- and twenty-first-century Japanese art.

The reaction of Soviet and Russian art history to the art of Japan over the past hundred years allows us to look at the complexity and problematic nature of the cultural exchange between Japan and Russia. The laboratory aims to mark the activity of Japanese artists in Russia, including their participation in exhibitions, establishing contacts with local artists and institutions, and unrealized projects and events.

One of the main aims of this project is to show how ways of constructing an alternative history of contemporary Japanese art, different to those versions that exist in the international space, are being formed. As well as demonstrating how (by which authors and using which methods) art was presented from the Japanese side, it is important to show how the domestic model of art history and criticism shapes the viewer’s attitude to foreign narratives.

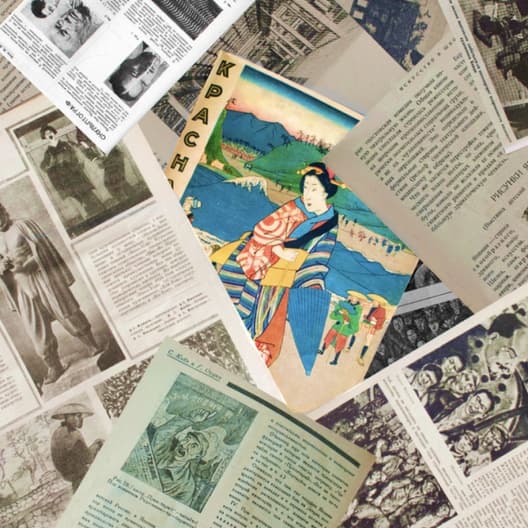

The laboratory focuses on understanding modern and contemporary Japanese art, architecture, photography, performative practices, and experimental Butoh dance in the later stages of Japanese art’s presence in Russia. It includes the creation of an archive that will bring together periodical materials that were one of the sources for this study. The preservation of this information is a tribute to anyone who has ever been involved in the exploration of this subject. Other plans include organizing educational programs and producing a book on the history of the representation of Japanese contemporary art in Russia.

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art is a key venue for exhibiting Japanese artists in contemporary Russia’s institutional space and actively promotes the culture of Japan in collaboration with J-FEST, a festival of contemporary Japanese culture. The Museum has shown Japanese artists on several occasions, both in group exhibitions such as JapanCongo (2011) and in the solo exhibitions Yayoi Kusama. Infinity Theory (2015) and Takashi Murakami’s major retrospective Under the Radiation Falls (2017). The laboratory will develop the interest of Russian audiences in the art and culture of Japan, emphasizing the importance of the cultural ties and friendship between the two countries.

Outcomes of the Japanese laboratory J100R

As part of the research laboratory J100R, which explored contemporary Japanese art and the history of cultural links between the USSR, Russia, and Japan, a research group led by Viktor Belozerov worked extensively in various archives. In the Russia State Archive of Literature and Art (RGALI) and the State Archive of the Russian Federation, using materials on the activities of the All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (VOKS) and the Union of Soviet Societies of Friendship and Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, the group was able to reestablish the chronology of cultural exchange between the USSR and Japan. Thanks to the assistance of staff from numerous Russian museums, including Grodekov Khabarovsk Regional Museum, Komsomolsk-on-Amur Museum of Fine Arts, Sukachev Irkutsk Regional Art Museum, Far Eastern Art Museum, Novosibirsk State Art Museum, Samara Regional Art Museum, and Radishchev Saratov State Art Museum, visual materials were added to the chronology and are now available for study as part of the Garage institutional archive.

An archive of prewar Soviet periodicals on the contemporary art of Japan, compiled by Viktor Belozerov during work on this research project, was published on the RAAN platform. This archive, together with a selection of recent literature on contemporary Japanese art, will be of use to specialists studying various aspects of Japanese art. Those who would like to familiarize themselves with the outcomes of the research in a non-academic format can access the educational course How to Show the Sun: Japanese Culture in the USSR, which comprises seven thematic blocks with short audio lectures.

According to Viktor Belozerov, “this mosaic of dozens of events, artists’ personal stories, links between people, works of art, and exhibitions will not answer every question (why we continue to have an attitude of superiority toward contemporary art forms from more distant places; how to prepare the viewer for this, both economically and culturally), but it remains important that such a subject, even if only from the Russo-Japanese point of view, allows us to look at ourselves and tackle our indifference to our own history and possible future.”