The first part of the overview for the exhibition The Other Trans-Atlantic was devoted to books on kinetic art outside of the Soviet Union. In the second part, Garage Research team look at publications on kinetic movement in the USSR and Russia.

Overview of Publications on Soviet and Russian Kinetic Art

The selection was prepared by Ilmira Bolotyan, Valery Ledenev, Maryana Karysheva, and Maria Litovchenko.

Viacheslav Koleichuk. Kinetizm [Kineticism]

Galart, 1994

‘Kineticism is art based on the idea of moving form. This does not only refer to the movement of an object in space, but also incudes any change, transformation—any kind of ‘life’ that develops in the work as it is observed by the viewer.’ With this clear and elegant definition artist, researcher and member of Mir group Viacheslav Koleichuk (1941–2018) opens his book on kinetic art.

Published in 1994, Kineticism might still be the only work written in Russian language to offer an exhaustive overview of kinetic art in the USSR and outside of it. Starting with Russian constructivism and the seminal exhibition of OBMOKhU (Society of Young Artists) in 1921 (he reconstructed its display for the Tratyakov Gallery in 2006), Koleichuk moves on to Alexander Calder’s mobiles and discusses experiments by Jean Tinguely, Bridget Riley, Jesús Rafael Soto and Julio Le Parc, paying special attention to the formal aspects of their compositions: the use of mirrors; creating a illusion of movement through the use of graphic linear patterns; making the viewer part of the work. His account is not strictly chronological but in-depth and draws on a wide range of sources, including literature that inspired artists whose work is analyzed in the book.

The closing chapters are devoted to Dvizheniye, Argo and Mir groups, light music experiments by Kazan-based Prometheus collective and Latvian artists (the ‘Riga group’ including Arturs Riņķis), whose works were included in the exhibition at Garage.

Viacheslav Koleichuk passed away only a few weeks before the opening of the reconstruction of his Atom—one of the landmark projects of Soviet kinetic art, originally created in 1968. Visitors can see the reconstructed Atom in Garage Square from May 6 to August 28. V. L.

Dinamicheskaya I kineticheskaya forma v dizayne. Metodicheskiye materialy [Dynamic and Kinetic Form in Design. Resource Materials]

VNIITE (All-Union Scientific Research Institute of Industrial Design), 1989

Compiled by Viacheslav Koleichuk, Alexander Lavrentyev, Selim Khan-Magomedov and Irina Racheyeva, this book is devoted to the actual practice of making mobile objects. As Viacheslav Koleichuk points out in the introduction, dynamic form captured the attention of Soviet artists from the Avant-Garde (Vladimir Tatlin, Aleksei Gan, Naum Gabo, Gustav Klutsis and Alexander Rodchenko were among those who experimented with it) until the very end of the USSR. Elements of kinetic art seeped into design, applied arts, light architecture, exhibition spaces and the everyday. The aesthetic potential of kinetic form often got neglected, which resulted in aesthetic flops, such as Gamma radiogram: created without professional designers, it reduced light music to ‘three light bulbs of different colour that blinked in the rhythm of the music.’

Authors of the book distinguish two waves of interest towards kinetic form. The first (in the 1920s and 30s) had to do with the development of new styles and art forms by futurist, cubist and constructivist artists, while the second (1950s and 60s) saw new artists implement the discoveries of the previous generations in light architecture, applied arts and exhibition design.

Discussing over 200 projects, with models and drawings, the book reveals the key principles of the making of dynamic and kinetic objects. The chapter Movement as Image begins with an analysis of representation of movement in European culture and the stereotypes it has created (movement as an arrow, boomerang or a running horse) and finishes with a discussion of experimental model making (Calder’s mobiles, Theremin’s self-titled musical instrument, Schöffer’s luminodynamic tower, works by Koleichuk and other Soviet engineers and artists). The closing section of the book, Artists and Their Concepts of Dynamic and Kinetic Form is essentially an overview of works and exhibitions by Dvizheniye collective. Along with well-known artists you will come across several names that have been forgotten. For example, Boris Stuchebryukov made objects of many layers using the resilience of materials. His Transformer Blade Fabric (1985) could transform into a cylinder, a dome or a cone.

Although it seems to have been written for professionals (designers, architects, sculptors and art historians), this collection of texts will also be of interest to the general reader. You will find out why the shape of the Parker pen became iconic; why one of the first models of amateur photo cameras featured horizontal metal lines; how American designers crushed stereotypes in European chinaware and what the pockets of the Soviet ‘universal coat’ could be transformed into. I. B.

Prometey. Demoversiya. Eksperiment obeshchayet stat iskusstvom [Prometheus. A Demo. Experiment That Promises To Become Art

Centre of Interdisciplinary Research in Contemporary Art, Kazan: SKB Prometey, 2017

Student engineering studio Prometheus was formed in Kazan in 1962 to stage Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus: The Poem of Fire. Later, the student initiative grew into a proper research institute, whose staff included scientists, engineers, artists, philosophers and musicians. Prometheus turned Kazan into the main Soviet hub of interdisciplinary projects at the intersection of art, science and technology. It produced a number of light music machines, as well as theater shows, films, conferences and video art experiments initiated by the studio’s leader Bulat Galeyev.

An exhibition devoted to Prometheus took place in Moscow in 2017. The catalogue includes a text on the history of the institute illustrated with archive photographs and exhibition views, as well as articles by Bulat Galeyev, Viacheslav Koleichuk, curators Boris Klyushnikov and Olga Shishko an and expert in Russian video art Antonio Geuza among other authors. M. K.

Vremya dvizheniya [Time of Movement]

Artstory Gallery, 2014

The 2014 exhibition at the Moscow Artstory Gallery brought together works by 12 artists of Dvizheniye collective, including Francisco Infante-Arana, Lev Nussberg, Rimma Sapgir-Zanevskaya, Vladimir Akulinin (all featured in The Other Trans-Atlantic at Garage) and Natalia Prokuratova.

In his article for the catalogue critic and scholar Sergey Khachaturov argues that our understanding of Dvizheniye ‘has become problematic, as many ideas by artists like Zanevskaya, Grigoriev, Infante, Koleichuk and Nussberg have been appropriated by the culture of street design and celebrations, the culture of entertainment.’ However, he continues, ‘contemporary high-tech design that brings to mind the illusionistic experiments of half-a-century ago is essentially different from the work of the great artists of the Soviet underground… as Dvizheniye experiments were never made for fun or entertainment purposes only, but were the practical part of the collective’s philosophy of art, their understanding of its essence and its relation to nature, technology and humanity.’

The publication abounds in illustrations, which include photographs from Dvizhenie archive of the 1960s and 70s and the 1966 Manifesto of Russian Kinetic Artists—the key text for the collective. V. L.

Francisco Infante, Nonna Goryunova. Katalog-albom artefaktov retrospektivnoy vystavki v Moskovskom muzeye sovremennogo iskusstva [Catalogue Album of Artefacts from the Retrospective Exhibition at Moscow Museum of Modern Art]

NCCA, 2006

This large format book of 500 pages is the catalogue for the 2006 retrospective exhibition of Francisco Infante-Arana and Nonna Goryunova at Moscow Museum of Modern Art. The concept of the ‘artefact,’ as understood and used by Infante, is partially explained in the article by poet and art theorist Vsevolod Nekrasov, who focuses on the mirror artefact in nature as ‘the signature, essential form in Infante’s work, his emblem that marries human-made objects with nature, structure with intuition, emotions with technology.’ Infante’s own text On the Concept of Artefact is also featured in the catalogue.

The publication contains Nekrasov’s poetry dedicated to Francisco Infante, an article by Nicoletta Misler and John Bowlt and Evgenia Kikodze’s 2002 interview with the artist. Works featured in the catalogue include the famous Spirals (Spiral of Infinity, 1963; Dynamic Spirals, 1964), painted china and ‘artefacts’ of different years. M. L.

Nussberg 1961–1979

Galerie Karin Fesel, 1979

The catalogue of the exhibition of one of Dvizhenie leaders Lev Nussberg, which took place in Wiesbaden in 1979, comes from the Leonid Talochkin Collection in Garage Archive. According to the inscription, Nussberg himself sent the publication to Talochkin and art historian Tatyana Vendelshteyn. The catalogue features works made from 1961 to 1979 with an introduction by Friedrich W. Heckmanns, who compares works by Russian kinetic artists to the masterpieces of the Russian Avant-Garde. This copy of the catalogue also features handwritten comments by Nussberg.

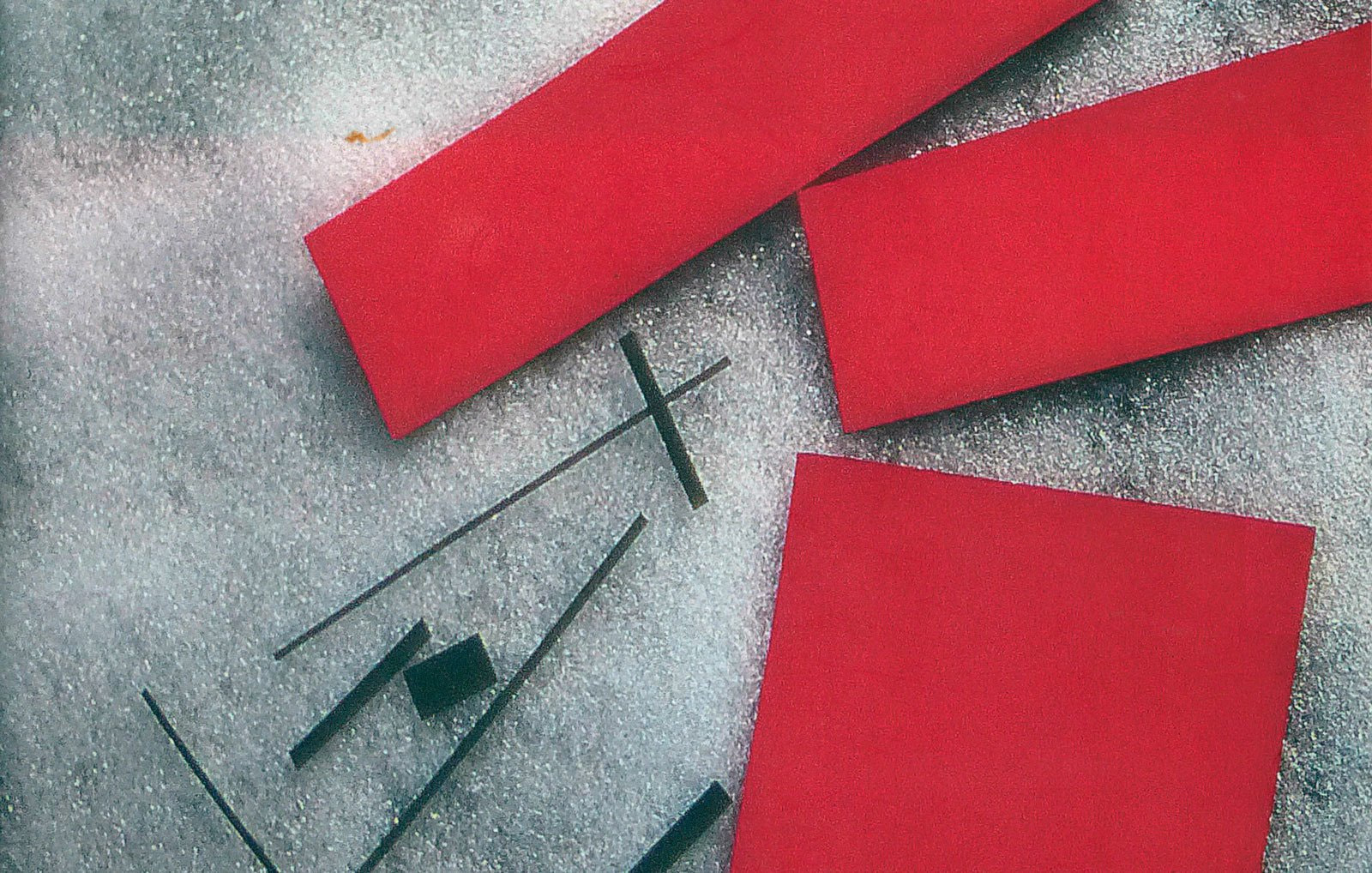

By the black-and-white photograph of his work In the Memory of Malevich (1961) Nussberg explain that ‘the square [in the painting] was of course bright red. I made it very much à la Malevich!’ By the painting Platinum Wave In an Abstract Landscape (1961), he wrote ‘I like this work (although it is an early one and far too red in this catalogue).’ ‘This is how I “illustrated” music,’ says the inscription by the drawing Invention (1962). V. L.