Preparing staff: etiquette, terminology and accompaniment during tours

Galina Novotvortseva—manager of the inclusive programs department for work

with the partially sighted and blind, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art (2015—2018)

What difficulties do you experience when visiting a museum on your own?

Oftentimes, employees are simply not ready to work with the blind: sometimes they're afraid that such people will ruin something or even break it. Sometimes people don't understand why [a museum visit] is necessary for [the blind] at all—because without vision, you can't understand or feel anything.

Larisa, 47 years old, blind

Who is the first person that a museum visitor encounters? It's not always an employee of the educational or tour department. The visitor is often met by a security officer. After that, they encounter employees of the museum's information department, the coat check, and so on. Contact with these employees forms a visitor’s first impression of a cultural institution. That is why one of the most important areas of work for the inclusive programs department at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art is to work with our staff.

Every three months, all Garage employees who work with visitors receive training on understanding disabilities, during which they learn about etiquette, terminology, and how to assist people with disabilities properly.

The frequency of such workshops is dictated by several factors:

- Partial staff turnover;

- Exhibition changeover;

- The need to repeat and reinforce information received at previous workshops.

In addition, the repetition of these workshops allows us and our colleagues to analyze organizational problems that

Veta Morozova, participant of the ‘Co-Thinkers’ exhibit, conducts a workshop for the mediator team at Garage Museum. 2016

became apparent when people with disabilities did, in fact, visit. In Russia and around the world, there are numerous manuals (including video courses—see the list of references at the end of the article) that anyone can read. Before creating a training program, you need to familiarise yourself with several sources of information on etiquette and accompaniment. In addition, specialists from organizations that work with people with disabilities, such as representatives of the All-Russian Society of the Blind, should be involved in the development and implementation of your first workshops. You can read more about formats of interaction with public organizations and foundations in the article “Promoting Programmes and Working with the Community” (p. 94).

It is important to understand that there are no established standards of communication and support in Russia for people with disabilities. Moreover, the medical model of understanding disability is also widespread among people with disabilities themselves. Therefore, it is essential to involve organizations and use methodological tools that are based on the social model of understanding disability. Before inviting an organization to conduct a training session at your museum, visit a similar event held by that organization elsewhere and make sure that they share a similar categorical framework for talking about disability. These training sessions often include general information. Their purpose is to overcome social and communication barriers when interacting with people with disabilities. As a result, the unique characteristics of work with museums are not taken into account. Based on the knowledge gained and the problems identified directly in the working process, a museum can develop its own staff training programs in the future.

For example, workshops for Garage staff consist of the following components:

- Concise information about forms of disability;

- Etiquette and accompaniment;

- Practical exercises.

Concise information about forms of disability

Depending on a museum staff member's age and experience interacting with people with disabilities, this section's content may vary. It is necessary to discuss the importance of working with this category of visitors with older museum employees. This part of the training program usually includes the following elements:

- General information about the forms of disability.

Discuss possible forms of disability, such as blindness, severe nearsightedness and farsightedness, reduced night vision, blurring or loss of parts of the visual image, and narrowing of the field of vision (including tunnel vision). Employees need to be aware of all of these forms so they understand that the people who might need help do not always carry a white cane. - Information about the capabilities of the partially sighted and blind.

There aren't many professions truly inaccessible to a blind person. Many people, for instance, know the musician Stevie Wonder. In Russian history, the most striking example of a successful blind man is Lev Semyonovich Pontryagin, an outstanding twentieth-century mathematician. One might also cite the example of English politician, academic, and former British Education and Employment Secretary David Blunkett, who was born blind.

You should find out about partially sighted and blind people who live and work in your locality. One can talk about the fact that almost all departments within Russian universities accept partially sighted and blind students. But can people imagine a blind historian without the opportunity to get acquainted with a historical museum's collection? Or a humanities specialist who can't visit art museums?

When discussing these issues, it is important to emphasize that a person with a disability has the same opportunities and rights as a person without them, but that it is instead society that builds barriers to prevent people with disabilities from enjoying these rights. At the same time, avoid placing people with disabilities on a pedestal.

- Discussion of existing stereotypes about a given form of disability.

Unfortunately, there are many stereotypes today about the partially sighted and blind. Stereotypes not only depersonalize a person in the eyes of others but can also adversely affect the quality of services provided to them.

Below are the most common stereotypes about the partially sighted and blind:

- All blind people are musical.

It is true that blind people are most often taught music, but this does not mean that the person you are talking to can play any

particular musical instrument, much less have mastered it. The incidence of musical gifted and genius is the same among people with disabilities as among people without them.

The blind can perceive space just fine using sound alone. Indeed, in cases of blindness and reduced vision, a person uses the remaining senses (for example, hearing) more actively. As a result, they can use them more effectively than a sighted person. However, the extent of such compensation depends on many factors. Other aspects of a persons physical and intellectual state, the amount of time that has passed since they lost their sight, or limited life experience can all hinder the development of compensatory hearing functions. Moreover, developed auditory perception can allow a person to understand the volume of space, but only a select few blind people can use their hearing to detect objects and obstacles.

- The blind have a “sixth sense” and even a kind of clairvoyance.

Of course, the very existence of such a phenomenon as clairvoyance is controversial. However, as with musical talent, this has nothing to do with blindness.

- Blind people’s fingers are especially sensitive. The blind can discover tumors, sprains, and other internal ailments by touch alone.

The development of a compensatory sense of touch, just like hearing, can often be noted among blind people. But even in this case, the degree of its development can vary greatly. Indeed, many blind people work as massage therapists (as during the Soviet period, the profession of massage therapist was one of the most accessible to the blind), but skills depend primarily on professionalism, not on the presence or absence of vision. Today, the blind are less likely to work with massage as with the development of assistive technologies; they have more opportunities for self-actualization.

- The blind always walk around with assistance and live with their families.

Many blind people move around the city without any outside help: they use the metro alongside navigation apps.

- The blind don’t use computers, touchscreen phones, or other gadgets

Special programs allow them to use practically any gadget. Many blind people prefer smartphones with touchscreens as more useful applications are being developed for such phones.

- Blind people are not as well-informed as people without disabilities.

Blind people have access to nearly all the information accessible on the internet.

Etiquette and accompaniment

Since there are no uniform rules of etiquette and accompaniment for the blind, the communication terminology and recommendations compiled by the Garage’s staff are given below.

Although Garage uses the “person-first” rule, partially sighted and blind visitors represent one of the few exceptions. This is because it is unacceptable to use terms like “visually impaired,” “limited vision,” or “suffering from visual impairment” within the framework of the social model of understanding disability. Such vocabulary immediately points towards a person's limitations without taking their individual experience into account.

When accompanying a partially sighted or blind visitor, it is necessary to verbally announce any obstacles, including the first and last steps on a stairwell

In addition, it is appropriate to use the same verbs and phrases for partially sighted and blind visitors as for people without disabilities. For example, blind people “watch” a movie, “look at” an exhibit, or “examine” an exhibit. If you are not comfortable using these expressions, choose neutral verbs, for example, blind visitors “get acquainted” with an exhibition.

When addressing a person, focus on their physical age. When not combined with other elements of development, blindness does not indicate any other learning or developmental disabilities.

- If you need to get the attention of a blind person in a public place, touch their forearm lightly, and introduce yourself. This is necessary so that the person understands that you are addressing them and knows with whom they are speaking. It is better to immediately ask the person's name to avoid intruding on their personal space in the future.

- When greeting a blind person, they might extend their hand for a handshake. Don't miss this gesture.

- A blind person might come to the museum with a companion. It’s important to remember that this is not necessarily

- If you need to step away even for a few seconds, be sure to let your blind visitor know about this. If someone else has joined your conversation, tell the blind person.

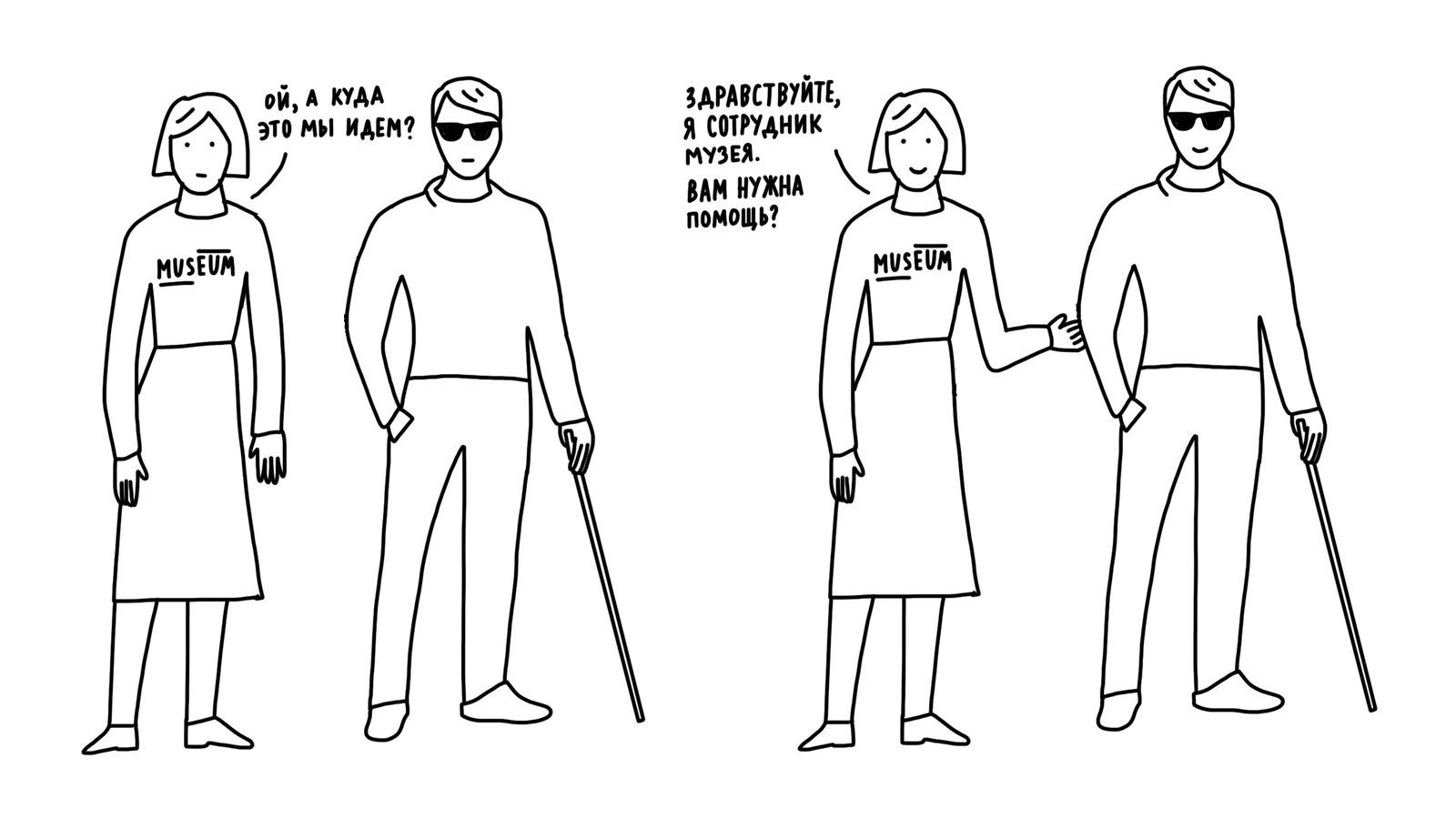

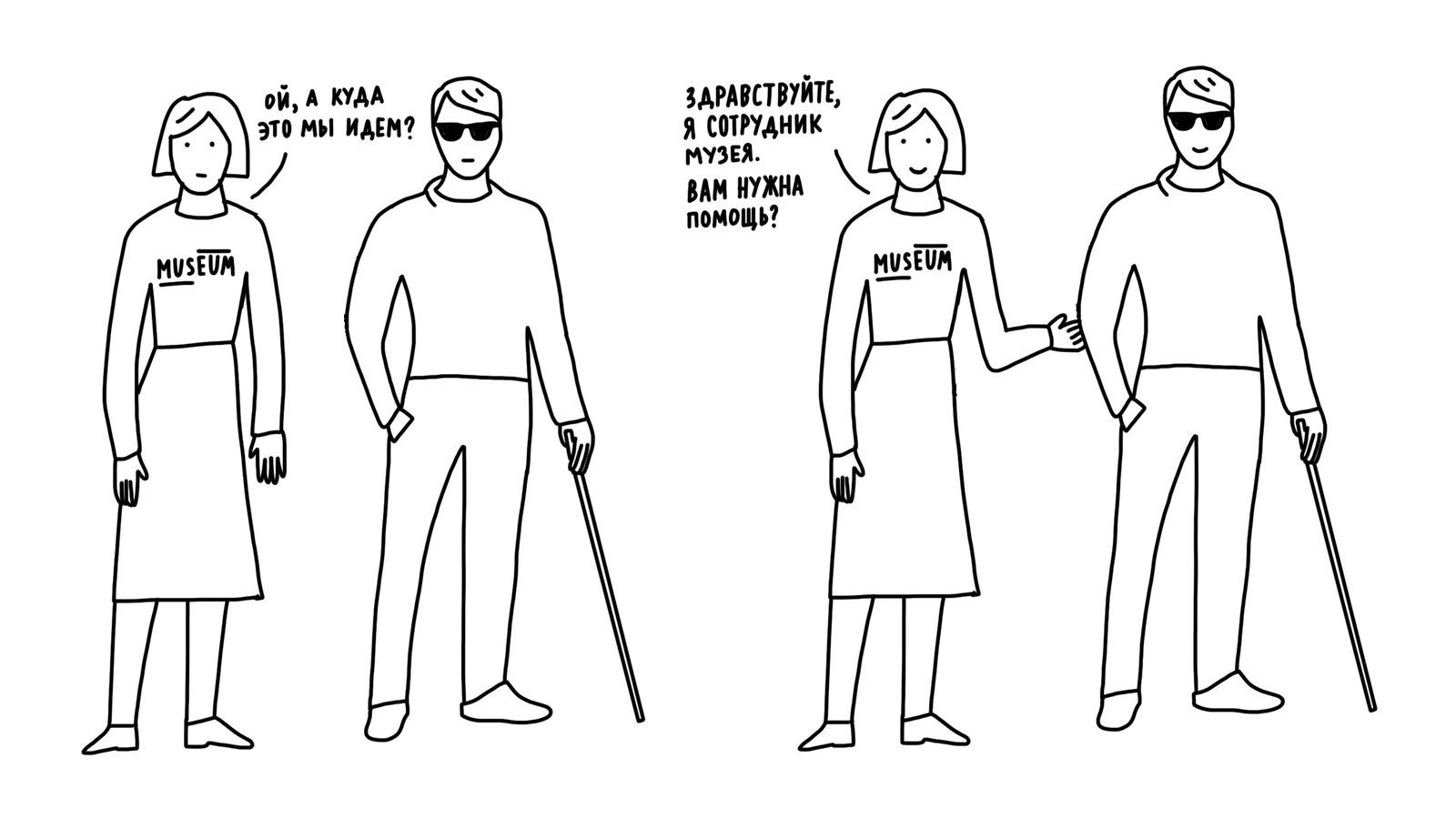

Left: ‘Now where do you think you’re going?’

a relative of theirs by any means. When speaking to a blind person in the presence of a companion, speak directly to the blind person.

Right: ‘Hello, I’m a museum employee. Do you need any help?’

Author: Nina Kuzmina - If you need to step away even for a few seconds, be sure to let your blind visitor know about this. If someone else has joined your conversation, tell the blind person.

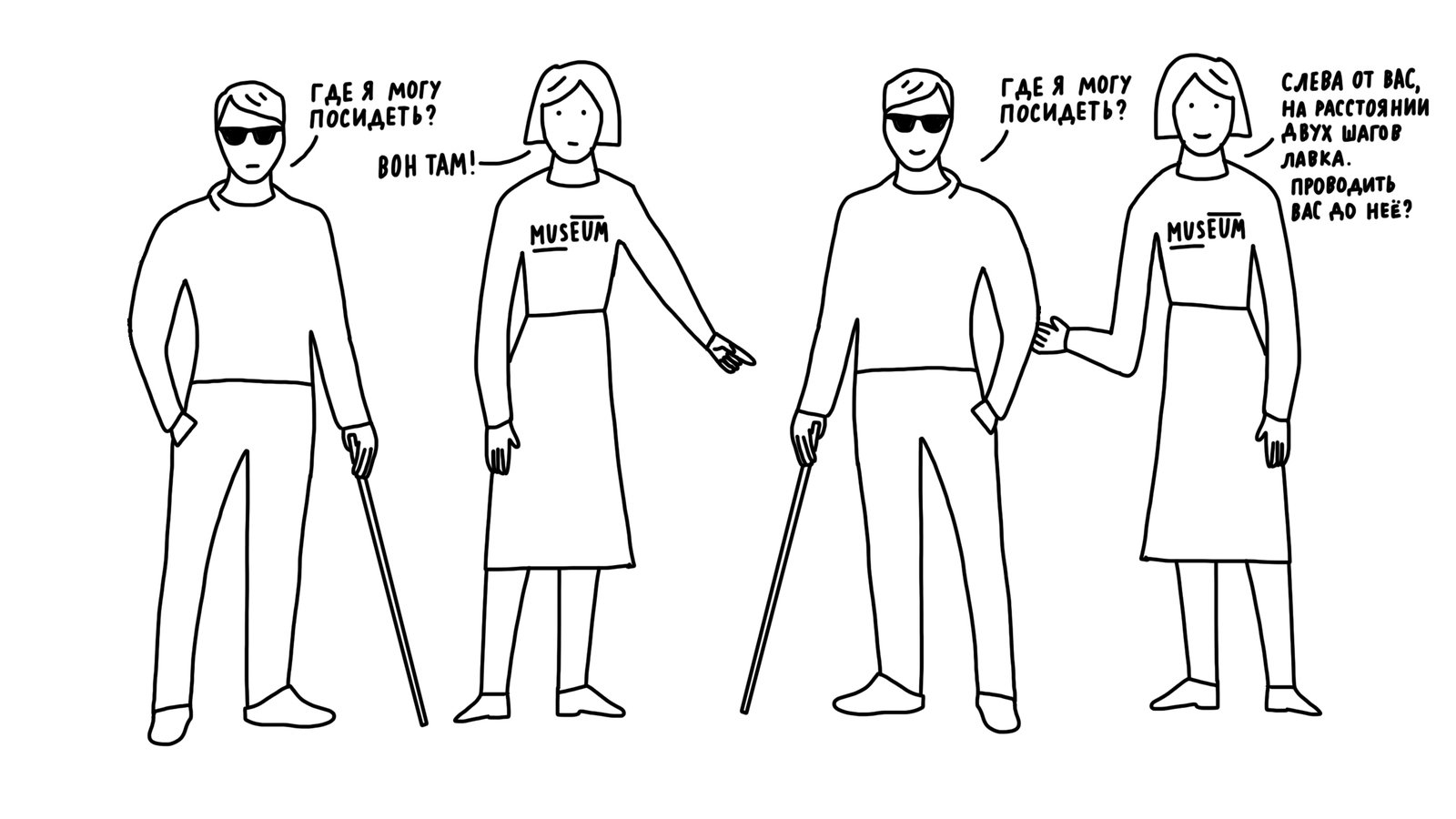

- Remember that blind people don't have access to your facial expressions and gestures. If you need to nod in a conversation with a sighted person or, for example, indicate the right direction with our hand, we need to duplicate this information with our voice in the case of a blind person.

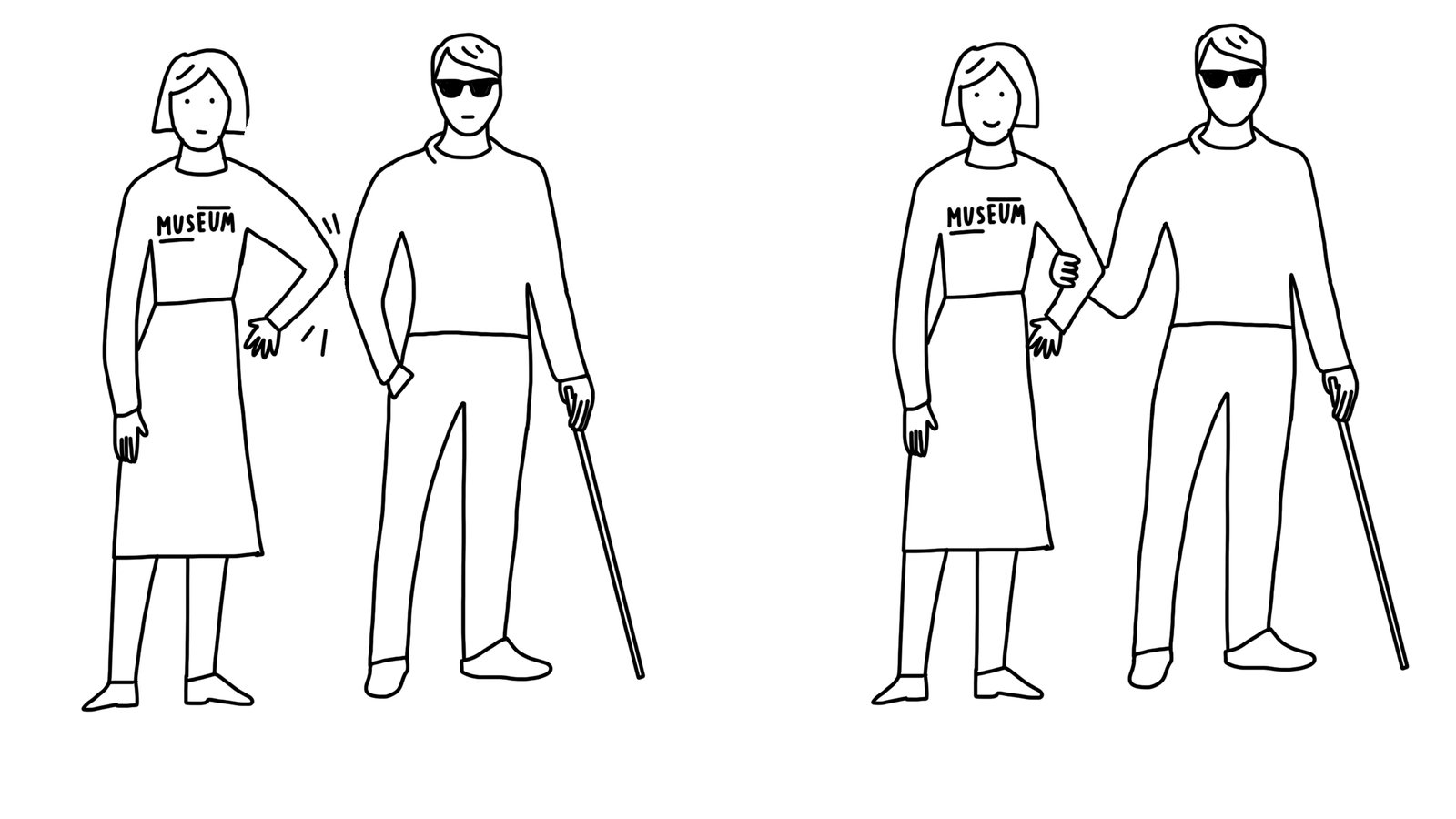

- If you notice that a blind or visually impaired person is experiencing difficulty, can't find something, or is going in the wrong direction, ask if your help is needed before you do anything. If the answer is yes, find out exactly how you can help. If the person refuses your help, do not impose and wait for them; if the person is still having trouble, ask again. If a person flatly refuses your help, and their actions do not pose a threat to the life and health of themselves or others, you should not continue offering help.

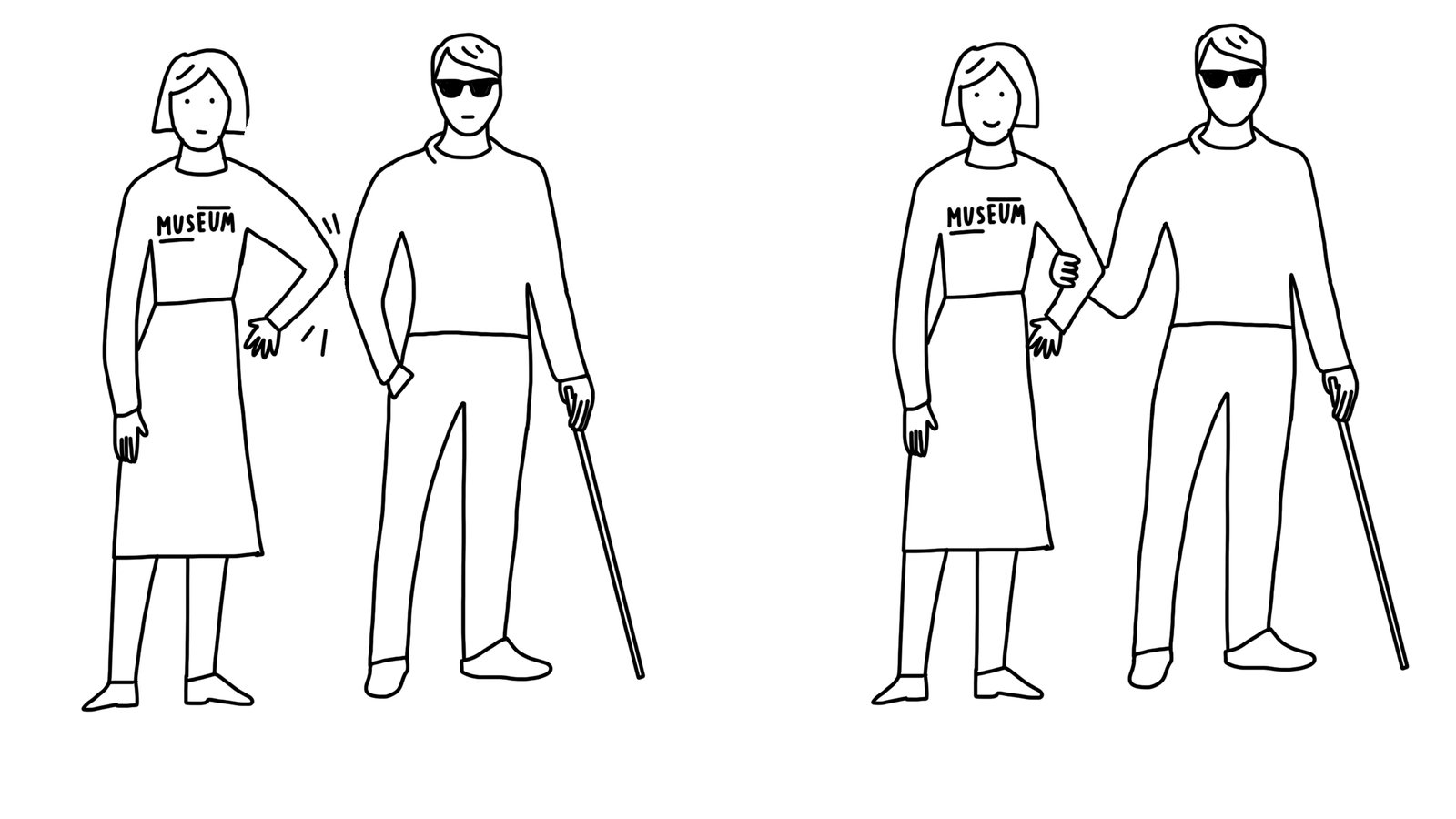

- If you need to accompany a blind visitor somewhere, ask which side you should stand or walk on. A companion usually stands to the left of the blind person. Bend your arm at the elbow and let your elbow touch your companion’s forearm

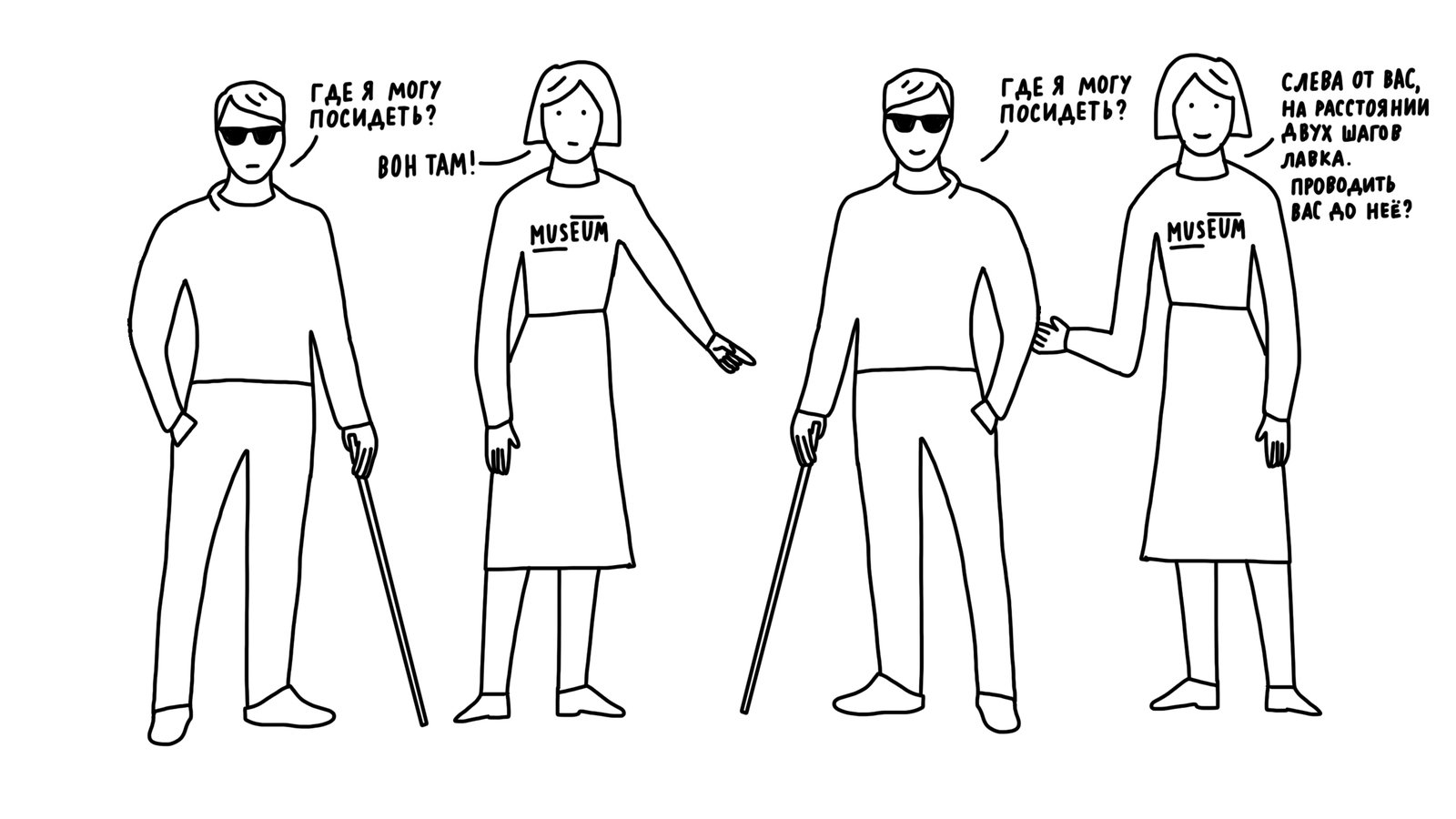

Left: ‘Where can I sit?’ ‘Over there!’

The person will take your arm themselves in a way that is comfortable for them.

Right: ‘Where can I sit?’ ‘There’s a bench two steps to your left. Can I help you find it?’

Author: Nina Kuzmina - When accompanying a blind person, announce the obstacles that arise on your way (like curbs, thresholds, stairs, and doorways). When approaching the steps, warn that a staircase is coming up and specify whether you will be walking up or down it. When you reach the end of the stairs, warn the blind person when they are on the last step.

- When passing through the doorway, tell the person which side the door is on. As a rule, the companion will open the door, and the blind person will close it.

- If you need to accompany a blind person to the toilet, bring them to the stall door and explain where the toilet is located, where the door lock can be found, and what kind of lock it is, where the toilet paper is, and how the toilet flushes. Wait for the person outside the door, then bring them to the sink. Place their hand on the tap and on the soap dispenser, then tell them whether the faucet is automatic.

- If you are helping a blind person to sit down, explain what is in front of them, such as a table and a chair, and put the blind person's hand on the back of the chair. If there is a table in front of the chair, show them the edge of the table in the same way. The blind person will then take a seat in a way that is convenient

Author: Nina Kuzmina

for them. - If a blind person asks you to read some text, read the text in full without skipping anything.

- Don’t discuss a person’s disability out of curiosity.

- A blind person's cane and guide dog are their property. You can't touch them without the owner's permission. In addition, according to the law,1 a guide dog is a rehabilitation device, and a blind person has the right to enter any building with it. When the owner keeps the dog on a leash, it does not pose any danger to the Museum's exhibits. However, if a blind visitor is being accompanied by a museum employee, the blind person might let the dog go. In this case, calmly ask the person to pick up the dog's leash.

Practical exercises

All information is absorbed better when theoretical knowledge is supported by practice. Therefore, it is important to allow participants to actively discuss the knowledge gained and independently arrive at the rules set out above. There is a special exercise in Garage's training program to achieve these objectives.

For example, participants are blindfolded in a number of exercises. The opinion that a blindfolded sighted person cannot feel the same things as a blind person is only partially true. A blind person's level of adaptation is strictly individual. It depends on the age at which they lost their sight and their personal experience of blindness.

Therefore, a well-designed situation allows a sighted person in a blindfold to independently discover the most common mistakes in communication with the blind.

One of the exercises is designed to help create the most comfortable situation possible. For example, it is necessary to accompany a blindfolded person only by voice without touching them, warning them that they will be left alone for a while, and so on. When discussing the results of this exercise, employees often formulate their own rules of accompaniment and etiquette. Another exercise is aimed at reinforcing those rules that have already been identified. It consists of the following: a group of sighted people must introduce themselves and accompany a group of blindfolded people somewhere, all while following the rules studied earlier.

People with disabilities should be involved in these training programs. This gives participants an opportunity to practice the knowledge they have gained while helping to achieve one of the main training goals: overcome stereotypes, awkwardness, and barriers in communicating with people with disabilities.

An example of leading a large group of visitors inside an exhibit without the use of tactile guidance

1. Federal law of 24.11.1995 № 181-ФЗ (edited 29.12.2017) ‘On the social protection of people with disabilities in the Russian Federation.’

Literature

- AUTHOR??, 2012. Znay, pomni delaya: rekomendatsii dlya volontera pri rabote s lyudmi s narusheniyami zritelnogo apparata [Know and Remember by Doing: Recommendations for Volunteers in Working with People with Visual Disabilities]. Мoscow.

- Perspektiva Regional Public Organisation of People with Disabilities. ‘Kultura obshcheniya s lyudmi s invalidnostyu. Yazyk i etiket’ [Culture of Communication with People with Disabilities: Language and Etiquette]. URL: perspektiva-inva.ru/ language-etiquette.

- Moskalets, E., Shingareva, E., Yaroshenko, I. et al. Metodika soprovozhdeniya lyudey s ogranicheniyami zreniya [Methodology of Accompanying People with Visual Disabilities]. Kharkov: Kreativa Kharkov City Public Organisation of People with Disabiltiies.

- American Foundation for the ‘Etiquette.’ URL: afb.org/info/friends-and-family/etiquette/23.

- Canadian National Institute for the Blind. ‘Step-by-Step. A how-to manual for guiding someone who is blind or partially sighted.’ URL: ca/en/about/Publications/vision-health/Documents/CNIB_STEP_BY_STEP_2012_ENG%20FINAL-s.pdf.

- Museum Access Consortium. ‘Working Document of Best Practices: Tips for Making All Visitors Feel Welcome.’ URL: org/resource/inclusionary-best-practices-tips-for-making-all-visitors-feel-welcome.