The history of the term “sensory safety.” How the sensory safety map at the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts was created

Alexander Sorokin, senior researcher at the Federal Research Center of the Moscow State Psychological and Pedagogical University, academic consultant to the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts

Evgenia Kiseleva, curator of the Accessible Museum program, head of the Interdisciplinary Projects Department at the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts

Abstract

One important facet of accessibility in public spaces is sensory safety, meaning the elimination of risk for those who have different sensory perceptions (people with autism spectrum disorder, epilepsy, and many other conditions). In 2016, the State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts began a project called Accessible Museum, and in 2017 formed a Committee on Sensory Safety. The committee included researchers, tutors, people with ASD, museum employees working with groups of such visitors, and members of parents’ organizations. They conducted a study of the museum space and created a map of sensory safety so that visitors with sensory disabilities could feel more comfortable in the museum. The Pushkin Museum’s map is distinguished from the majority of its counterparts by the focus it places on safety, rather than risks: in other words, rooms with minimal and moderate sensory load. In addition, the map offers information on what a visitor with increased sensory sensitivity should do in an unfamiliar setting if they need to lower their stress level.

A trip to a museum is an event for which people prepare and which creates memories that last a lifetime. Rooms with classical painting and contemporary immersive installations are typically organized in order to make impressions on visitors and elicit emotional responses. Exhibition projects are engineered for multisensory interaction, engaging numerous senses in the experience of viewing art. However, both children and adults may experience exhaustion and stress in a museum from the waiting, crowds, rules, and need for concentration over a long period of time that are part and parcel of the experience.

One of the risks faced by visitors to a museum or gallery is sensory overload1, caused by the overstimulation of smell, touch, taste, sight, and hearing. In addition, a person’s experience of spatial and performative art and exhibitions is influenced by proprioception2.

Anyone can find themselves in a sensory overload situation, but people with higher sensory sensitivity are especially at risk. They experience great pain from environmental irritants that are insignificant or entirely unnoticeable to others. What may not upset one person could be unpleasant or even unbearable for others. Often, increased sensitivity is connected to a person’s state at a given moment (people react more strongly to irritants when they are sick, tired, etc.), but it can also be a personality trait or a manifestation of ASD, post-traumatic stress syndrome, schizophrenia or epilepsy. In addition, psychological hypersensitivity and clinical manifestations of disorders have different mechanisms of interacting with the brain3.

In medical literature, manifestations of sensory overload (and the concept itself) receive insufficient attention, while the main recommendation for people with heightened sensory sensitivity is to avoid irritants whenever possible4. Different sense organs are typically studied in isolation, and as yet research has not yielded results that would be of use in planning the work of specialists in non-medical professions (for instance, museum employees). In this article, heightened sensory sensitivity is understood as an increased reactivity to typical stimuli, when the intolerance of irritants is manifested through undesirable behavior, including the desire to leave the museum.

Nuances of sensory perception are most often mentioned in the context of preparing children, teenagers and adults with ASD for a museum visit. According to modern diagnostic criteria, these people are characterized by specific challenges with social interaction and communication and stereotypical forms of behavior. The latter group of diagnostic symptoms include differences in sensory perception defined by the DSM-5 as “hyper-” or “hyporeactivity” to incoming sensory signals from the environment: for instance, seeming indifference to pain or high temperatures, a negative reaction to particular sounds or materials, persistent smelling or touching of objects, and an excessive fixation on intrusive lights or movements5. In the museum context (with rare exceptions), hyperreactivity is typically observed: people react to sensory irritants more acutely. Meanwhile, instances of hyporeactivity (when the reaction is much weaker) remain unnoticeable. However, the aforementioned diagnostic criterion is by no means a prerequisite, and not all people with ASD experience sensory disruptions.

Typically, people with ASD or their companions know about such challenges and try to avoid places with an especially high likelihood of sensory overload. This is one of the reasons why museums must be as honest as possible in communicating to visitors information about what efforts are being taken to create a comfortable environment from the perspective of possible irritants, as well as any limitations of those efforts.

The majority of museums do not have the capacity to completely eliminate sensory risks, particularly irritants connected to sight and hearing. Echoes in the exhibition spaces, the noise of other visitors, unexpected or unusual sounds made by the items on display, or the loud voice of a tour guide may be no less dangerous than the obvious risks of extremely bright lights, sharp changes in lighting between rooms, and so on. But we should not forget that other sensory organs also can also have irritants, like new and intense smells or the need to climb steep, twisting stairs. Overstimulation may result from the need to experience some kind of sensory stimulus. A person who is accustomed to touching the corners of objects will experience discomfort when touching exhibits is not permitted. In short, such unfamiliar spaces as museums experience difficulty not only with preemptively eliminating sensory risks but also with identifying them in the first place. In attempting to create a comfortable environment they must also consider other risks that are not sensory in and of themselves: drops in elevation, lack of seating, open doors, dangerous stairwells, unprotected exhibit items, etc.

There are a number of ways of making a museum space, the most important of which is by educating employees. They should be aware of the nuances of sensory perception and have the skills necessary to make a museum visit comfortable for all visitors.

Sensory maps are also of help to visitors and their companions when preparing for a visit to an institution where sensory risks are present. They come in many different forms. Some of them denote only risks (places with large crowds, spaces with bright lights, etc.), while others also mark areas with a lower risk level. An example of the second type is the British Museum's sensory map. Places with high and low noise levels, strong smells, and crowd densities are marked with pictograms, while museum spaces with natural and dim light are highlighted in different colors. Such maps contain detailed information about sensory risks and are unquestionably useful to people preparing a visit, allowing them to plan out their walk through the museum. But their effectiveness is considerably reduced if a person has a lower threshold for several different kinds of stimulation or modalities. As a result, when a visitor or their companion first sees the map upon arriving at the museum, they must quickly make decisions about which spaces to avoid.

The creation of a sensory map that could be used both while preparing for a museum visit and at the museum itself was one of the challenges tackled by the Accessible Museum project, which was launched by the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in 2016.

On February 14, 2017 the committee on sensory safety was formed. Its members included:

- A. Sorokin (Federal Research Center for organizing comprehensive accompaniment for children with ASD, the Neurophysiology Laborary at the Academic Center for Psychological Health, the Academic-Practical Center of Pediatric Psychoneurology of the Moscow Department of Health);

- N. Polyakova (Absolut-Pomoshch [Absolute Help] charitable foundation);

- I. Flikt (Reakomp Non-governmental Institute of Professional Rehabilitation and Personnel Training of the All-Russian Association of the Blind);

- K. Novikova (Vykhod [Exit] Charitable Foundation for Solving the Problems of Autism in Russia);

- Y. Akhtyamova (Center for Medical Teaching Regional Charitable Non-governmental Organization);

- E. Bagaradnikova (Kontakt Regional Public Organization for Aid to Children with ASD);

- I. Shpitzberg and A. Steinberg (Nash solnechniy mir [Our Sunny World] Center for the Rehabilitation of Children with Disabilities);

- Employees of the State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts: T. Potapova (head conservator), V. Sergeev (head engineer), I. Bakanova (deputy director for research), M. Zhuchkova (head of the visitor services department);

- Members of the Accessible Museum working group: E. Kiseleva, M. Dreznina, O. Morozova, and A. Dzhumaeva.

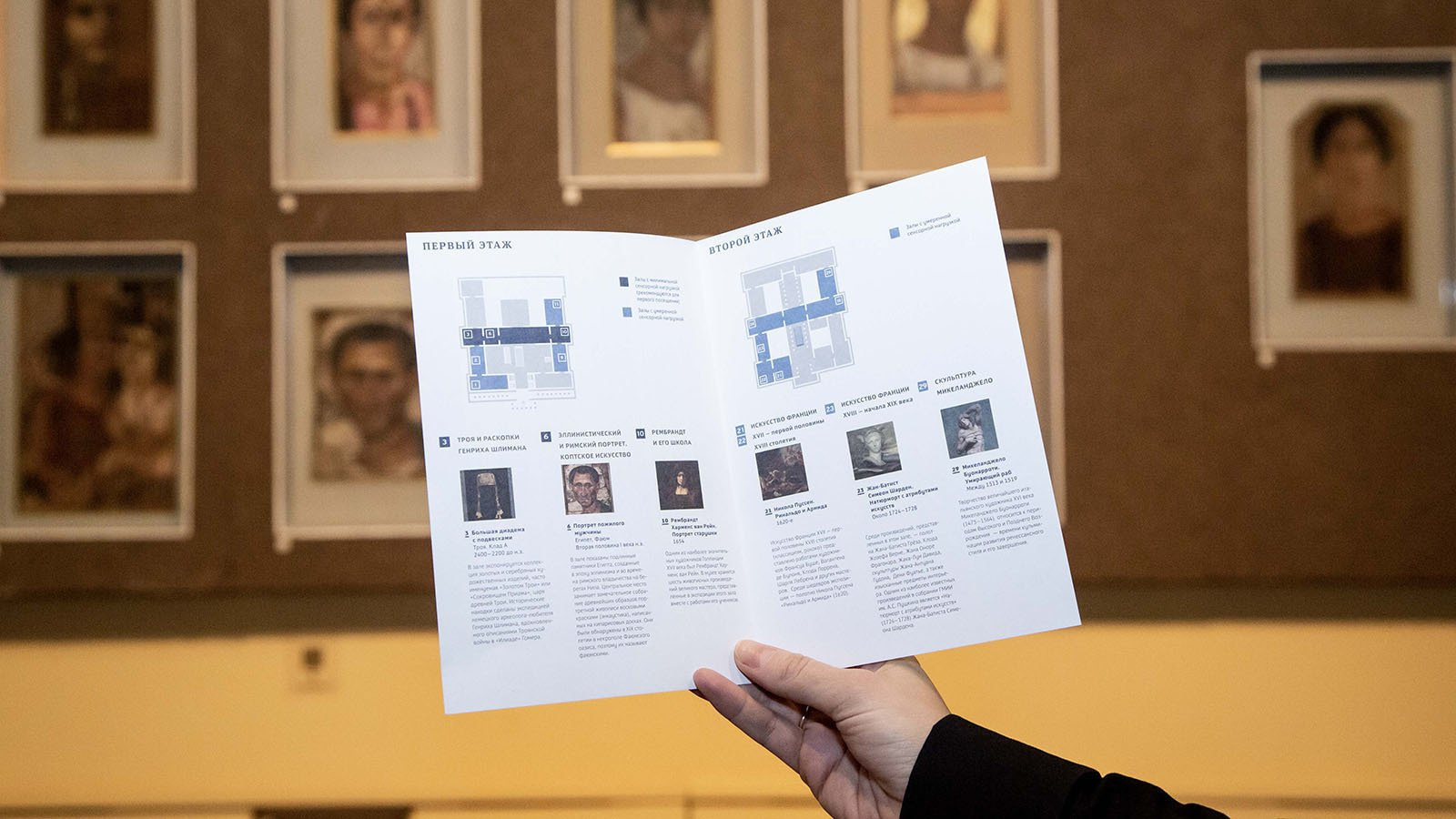

As a result of these meetings between museum employees and partner organizations, we decided to focus on identifying safe spaces in areas of the Main Building of the museum and the Gallery of 19th and 20th Century European and American Art, where sensory and other risks are among the lowest. This work gave us the term “sensory safety map.” Working with people with ASD, museum employees who work with visitors with ASD, and members of parents’ organizations, we made a careful study of the museum space and created a map to help visitors with sensory challenges to feel more at ease and adapt more quickly. The State Pushkin Museum’s map is different from most of its international analogues in that emphasis is placed not only on risks but also on rooms with minimal sensory loads that are recommended for first visits to the museum by people with a lower sensory threshold. It features information on where to go in order to help a person who finds themself in an unusual place or situation avoid potential overload.

“Sensory safety” is a new field for industries outside of the Russian museum sphere, even though the concept of safety has existed since Cicero and Seneca. At the time, the word “securitas” meant an absence of disease, cares, and reasons to worry6. This meaning has been preserved, but has faded into the background. A new meaning appeared, primarily connected to protection from threats and danger. The words “Sicherheit” (German), “security” (English), securité (French), seguridad (Spanish), sicurezza (Italian), and others have spread throughout the world, either by imbuing related words with additional meaning or creating obvious or subtle loan words7. But the world continues to change, along with notions of security and safety. In the context most familiar to us, this understanding only crystallized in the twentieth century. Philosopher Alexander Panarin believes the official date of the term’s recognition and spread to be 26 October 1945, the day of the UN Charter’s ratification by the majority of its founding members and the five permanent members of one of the two main bodies of the organization, the Security Council. In this context, public focus on “sensory safety” in the twenty-first century continues the process of conceptualizing safety and security as key values of human civilization.

The creators of the State Pushkin Museum’s sensory safety map aimed to use a new approach to creating an accessible environment in a modern museum, acknowledging the fact that no one perfect visitor path through the museum exists. Sensory safety is far from the only criterion in planning a visit to a museum or an encounter with an exhibition. Rooms with minimal sensory load are suggested as the most accessible for a first visit by people with lower sensory thresholds. It is presumed that this information will be useful to visitors who understand that the museum is making an effort to create a comfortable environment with sensory challenges, but do not know where to start their journey. A clear map will help relieve their doubts and fears.

Sensory safety is not limited to employee training and museum signage. It also includes one of the aspects of the professional exchange program, the Inclusive Practices Summer School and the Accessible Museum Conference, which accompanied the annual Inclusive Festival, held by the State Pushkin Museum since 2017.

In spring 2018, thanks to the presentation of the museum’s innovative map, the museum community began to discuss a new criterion of accessibility: sensory accessibility. In 2020, the Inclusive Museum working group of ICOM Russia (A. Steinberg, P. Bogorad, E. Kiseleva, L. Talyzina, D. Khalikova, N. Cherkasova, A. Sorokin, and A. Shemanov) developed a glossary and a series of control parameters to ensure the comfort of visitors with developmental disabilities, where a definition of sensory safety (accessibility) applicable to museums was proposed:

“Sensory accessibility is a set of measures, including provision of information about sensory risk factors (physical objects whose function have considerable effect on sensory organs and the potential to cause sensory overload), the provision of help in the case of sensory overload, and the alternation (when possible) of certain objects that cause sensory overload. Sensory accessibility also includes informing employees and visitors who do not possess altered sensory sensitivity about behavioral standards in the museum and at events should visitors with differing levels of sensory sensitivity be present, and creating alternative options to accommodate their presence.”8

This is just the beginning of tackling sensory risks and safety in museum spaces. The more museum employees join in this effort, the more useful discoveries and solutions will emerge.

1. Sensory overload is a state in which a person cannot handle the sensations experienced through the sense organs and in which they may lose their spatial orientation, self-control or capacity for speech. Examples include: the inability to simultaneously watch a television program and hold a conversation, spatial disorientation in case of excessive noise, and others. (List of control questions and recommendations for ensuring accessibility in museums for visitors with mental disabilities. ICOM Russia, 2020).

2. Proprioception (or muscle sensation) is a set of sensations that arise through the activation of the body’s muscular system. Through proprioception, a person learns to compare objects, essentially going through “an elementary school of object-oriented thinking.” From: Sechenov, I.M. On object-oriented thinking from a physiological perspective / I.M. Sechenov // Russian Thought. — Moscow, 1894. — year 15, book I. p. 255–262.

3. Acevedo, B., Aron, E., Pospos, S., & Jessen, D. (2018). The functional highly sensitive brain: a review of the brain circuits underlying sensory processing sensitivity and seemingly related disorders. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 373(1744), 20170161. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0161.

4. Scheydt S, Müller Staub M, Frauenfelder F, Nielsen GH, Behrens J, Needham I. (2017). Sensory overload: A concept analysis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 26(2):110-120. doi: 10.1111/inm.12303.

5. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

6. Перси У. От Сенеки до publica sicurezza: эволюция понятия «безопасность» в итальянской культуре // Безопасность как ценность и норма: опыт разных эпох и культур. Отв. ред. Сергей Панарин. СПб.: Интерсоцис, 2012. С. 177–187.

7. Безопасность на Западе, на Востоке и в России: представления, концепции, ситуации. Институт востоковедения РАН. — Иваново: Иван. Гос. Ун-т, 2013. С. 8.

8. List of control questions and recommendations for ensuring accessibility in museums for visitors with mental disabilities. ICOM Russia, 2020.