A lecture by Natalia Ryabchikova on the relationship between Soviet and Japanese cinema, and a screening of one of the earliest horror films, A Page of Madness, will conclude the public program of the Museum’s VOKS kinema Research Laboratory.

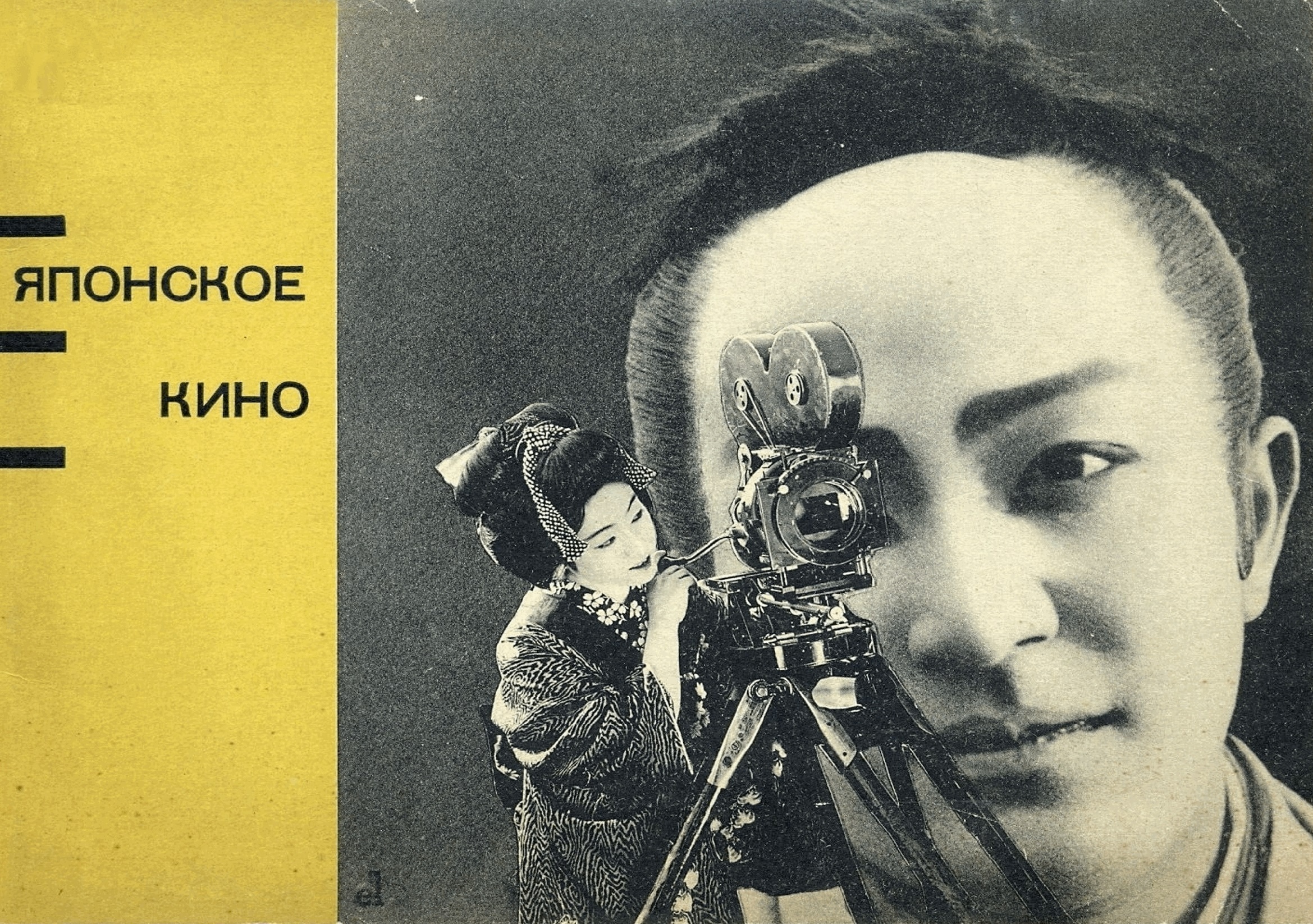

After Japan recognized the Soviet Union in 1925, a brief but active period of exchanges between filmmakers from the two countries began. Japanese intellectuals visited the USSR even more frequently than their Western counterparts, although Moscow and Leningrad often served mainly as transit points on their way to Europe. Japanese filmmakers and journalists turned to the relatively inaccessible Soviet experiments in film as a potential alternative to European and American cinema. The culmination of this mutual interest was the 1929 exhibition of Japanese cinema organized by the All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (VOKS), which was, in fact, the first international film festival ever held in the Soviet Union.

However, in the late 1920s this relationship was also a story of mutual misunderstanding. Sympathetic and curious Soviet critics and filmmakers—including Sergei Eisenstein, who was in love with the Land of the Rising Sun—were not prepared to accept Japanese films on contemporary themes and favored the samurai jidai-geki among the works presented, even though they criticized the genre for archaism. Inspired by the Kabuki theater tour (1928) and the films screened at the exhibition, Eisenstein wrote his now-classic essay “Beyond the Shot” (immediately translated into Japanese), in which he reproached his Japanese colleagues for drawing insufficiently on their own theatrical traditions. Conversely, the first Soviet film to find real success in Japan was not an avant-garde masterpiece (by Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pudovkin or Dziga Vertov) but the German-shot melodrama The Living Corpse, based on a work by Leo Tolstoy.

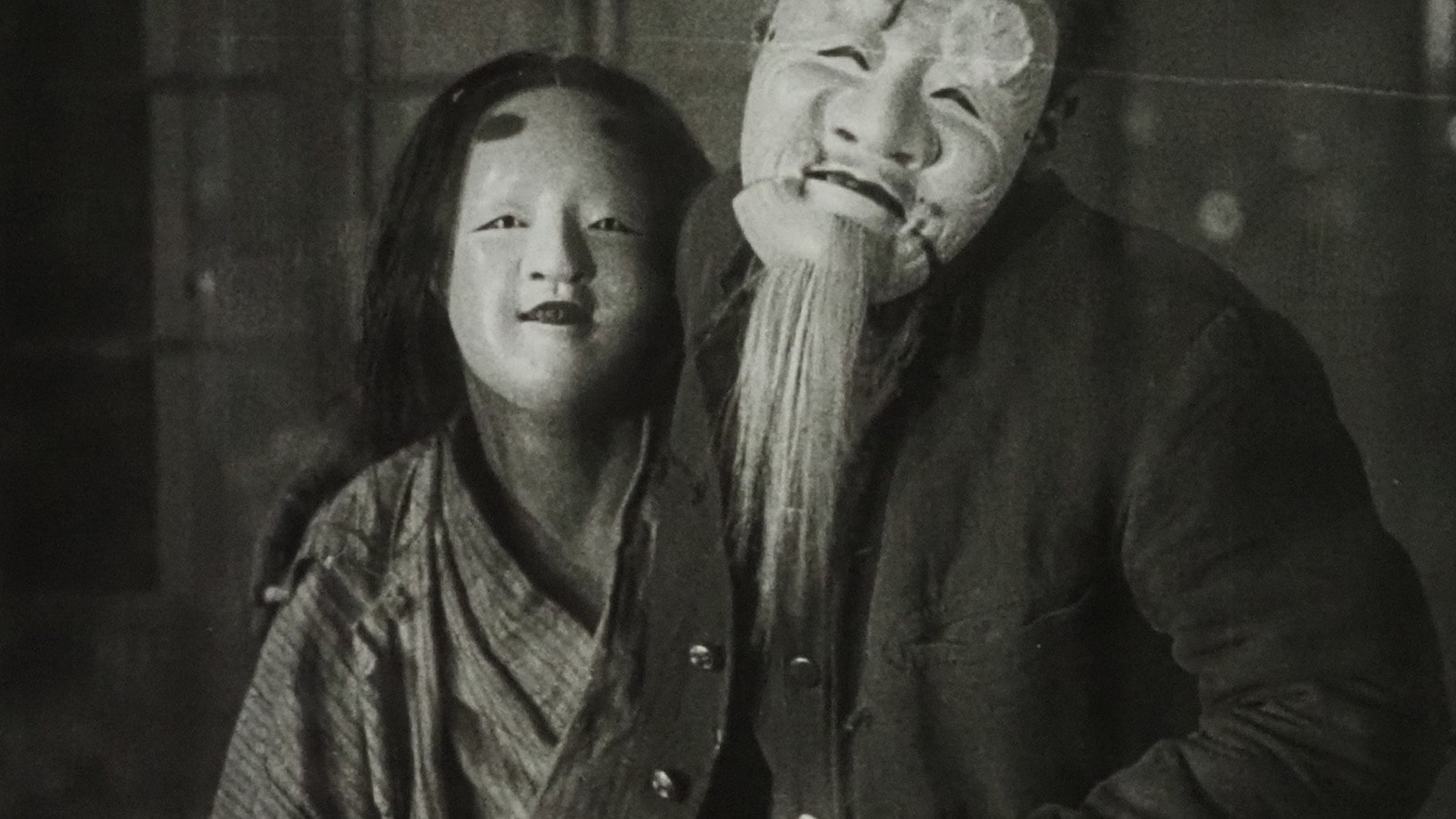

Among the filmmakers who traveled to the USSR was Teinosuke Kinugasa, a pioneer of Japanese cinema, whose Crossroads (1928) was distributed in Europe. It was not shown in the Soviet Union, however, despite the director bringing the film through Moscow. His ultra-avant-garde film A Page of Madness, made in 1926, later lost during World War II, and rediscovered only in 1971, likewise could not be screened in the Soviet Union. Instead, Kinugasa’s far more traditional (now lost) film The Brave Man of Kyoto (1928) was seen by hundreds of Soviet viewers at the VOKS exhibition. The irony is that A Page of Madness was the work that most closely aligned with the aspirations of the European (and Soviet) cinematic avant-garde. Kinugasa created a film in which the visual dominated over explanatory intertitles or the commentary of benshi, the professional narrators who accompanied screenings in Japan during the silent era. The action itself fused modernity with imagery drawn from traditional culture.

A Page of Madness

Dir. Teinosuke Kinugasa

Japan, 1926. 79 min.

A Page of Madness is considered one of the earliest horror films. An experimental work, it combines elements of traditional Japanese theater with modern European art. One of the founders of Japanese cinema, director Teinosuke Kinugasa, layers phantasmagoric, sometimes surreal, and often terrifying scenes, with the plot centering around a madwoman in a psychiatric clinic, her husband, who takes a job there to stay close to her, and their daughter, who is about to get married.