Dance Cooperative Isadorino Gore: An Ethical Rationale for the Project Soviet Gesture

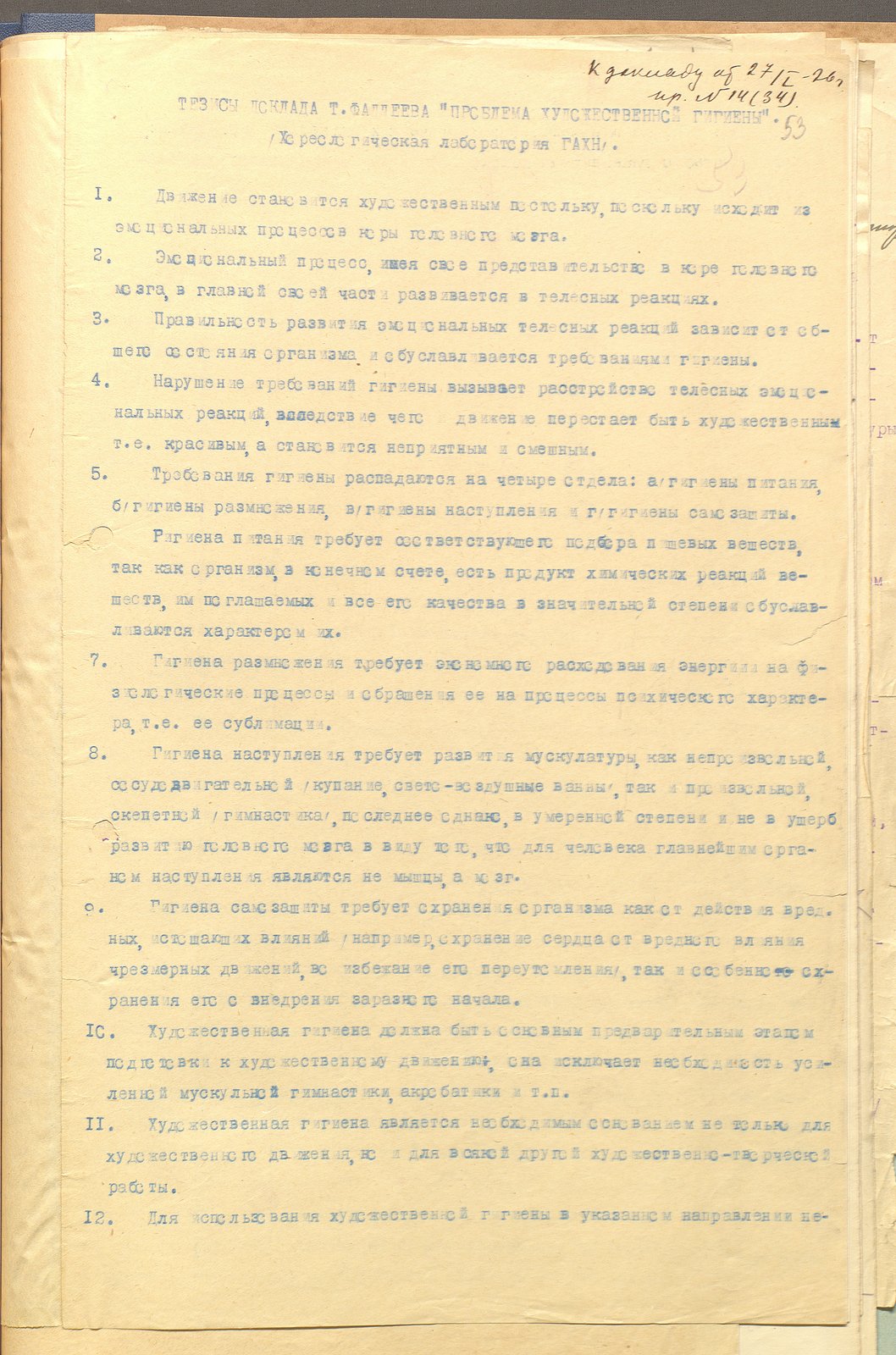

Below is an excerpt from Manual for the Practical Use of a Dance Archive: Experiments in Choreology, or Where the Soviet Gesture Has Led Us, a text currently being prepared for publication as part of the research project Soviet Gesture by the dance cooperative Isadorino Gore. The Manual is based on the cooperative’s study of the archive of the Choreological Laboratory at the Russian Academy of Artistic Sciences (1922–1930), and will be published as part of the Garage Field Research program.

Dance as an art form and a means of social communication has an agency that suggests specific forms of action and perception. For example, classical dance has always been, and remains, an unquestionable cultural staple in authoritarian regimes because it is based on—and communicates—a certain set of values: a strict hierarchy, fierce competition, and the lack of horizontal connections or solidarity. Contemporary dance emerged in countries that chose the democratic path, and its practices reflect universal human values, such as personal freedom and freedom of expression, non-violence, tolerance, and somatic and civic awareness. As dancers and choreographers educated in both traditions (classical ballet and Western contemporary dance), we have witnessed the transformation of our own values. Familiarizing ourselves with a new dance tradition and, therefore, a new set of values, we started seeing ourselves and the world differently. A side effect of this transformation was a reluctance to study the artistic experiments of the Soviet era due to a conflict of ideologies. By studying the genealogy of contemporary dance in Russia, we are trying to overcome our own self-colonizing tendencies (more on that in “Us” and “Them”: Unrecognized Russian Dance and the Imaginary West, a discussion with Anna Kozonina, Anastasia Proshutinskaya, and Christine Standtfest) and contribute to the development of the local cultural scene, enabling to it build an equal relationship with international trends.

Dance Cooperative Isadorino Gore

Study for the performance Soviet Gesture, 2018

Photo: Evgeny Vtorov

Our post-Soviet identity imposes certain limitations on our research focused on the Soviet past, yet it is the main reason and the driving force for this project. Very often, opinions on the Soviet legacy are based on personal emotional experiences, political beliefs, and limited information rather than facts, and this breeds prejudice. The state’s tendentious policy of sacralizing certain historical facts and sliding others under the carpet hinders the critical analysis of Soviet experiments and the work of memory. As a result, this work is performed by a narrow circle of researchers and activists and does not become accessible to the public. That is why the material that our research is focused on still carries a strong emotional charge.

In studies of historical heritage, working through ethical issues is important for professionals and the audience, allowing them to avoid the sacralization of both historical and living figures. In many countries the history of dance includes problematic areas which can be unpleasant but necessary to relate. The fact that icons of expressionist dance Mary Wigman, Gret Palucca, and Rudolf Laban were involved in the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games in Berlin in 1936 is well-known, but that does not diminish their contribution to the development of dance. A sober perspective on the cultural importance and social behavior of individuals allows us to be constructive in working with heritage and prepares fertile ground for a critical analysis of contemporary cultural trends.

Dance Cooperative Isadorino Gore

Site-specific performance Escalation of Heroism at Worker and Kolkhoz Woman Museum and Exhibition Center, Moscow, 2015

Photo: Ekaterina Pomelova

Current trends in Russian contemporary dance have grown out of an aesthetic hierarchy based on the unspoken consensus that contemporary dance came to Russia during perestroika. That period, and the years that followed, were indeed a time when many new faces appeared on the Soviet and post-Soviet contemporary dance scene, and when those who had been experimenting with similar practices previously became visible. This process was actively supported by cultural institutions from Western Europe and North America, the inherent mission of which is “to make the world a better place.” This involves helping people from countries that have undergone a crisis caused by radical political and economic change to adapt to life in a new, globalized world. Such institutions organize education programs that introduce people to the values of the “free world” (see the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights), and support projects that reflect the global cultural agenda. Across the former Soviet Union, the agenda in the field of dance involved exchange programs and support for dance festivals and summer schools. The type of dance that was shown or taught through those projects was new and exotic, very different from the bold experiments undertaken at their own risk by individual enthusiasts during the Soviet years.

From our observations, such international support programs appear to last around ten years. This period is believed to be sufficient for the emergence of independent cultural institutions within the country, even if that is not always the case.

Nevertheless, this period is sufficient for an entire generation of choreographers to begin to believe that real contemporary dance is a Western cultural phenomenon with a well-documented history, certified techniques, large companies that enjoy government funding, and a generally well-developed infrastructure.

It is also sufficient for the new generation of professionals to integrate into the global world. When the support programs end, these professionals are faced with a choice: they can either continue to build their careers on the global stage (they have had the time to develop the necessary skills) or stay and work in their country, relying on altruism, optimism, and the support of their families. The departure of international donors not only results in a lack of funding but also in the disintegration of the active core of the scene, which puts extra pressure on the local culture.

Long-term international support also creates a reliance on the import of knowledge and builds aesthetic hierarchies which reflect that reliance: international trends are considered more important than local ones as they are supported by international institutions. Such hierarchies persist not only in Russia but in every second- or third-world country that has had to recover from regime change and is susceptible to the influence of international cultural institutions, which is expressed in terms of self-colonizing reflexes. Despite these issues, international support does foster cultural development: exchange programs help people to build connections, broaden their horizons, and experience dancing and living in different cultures. In pursuing their stated missions, international organizations do indeed integrate communication practices that reflect “universal values”, rather than simply stating their existence.

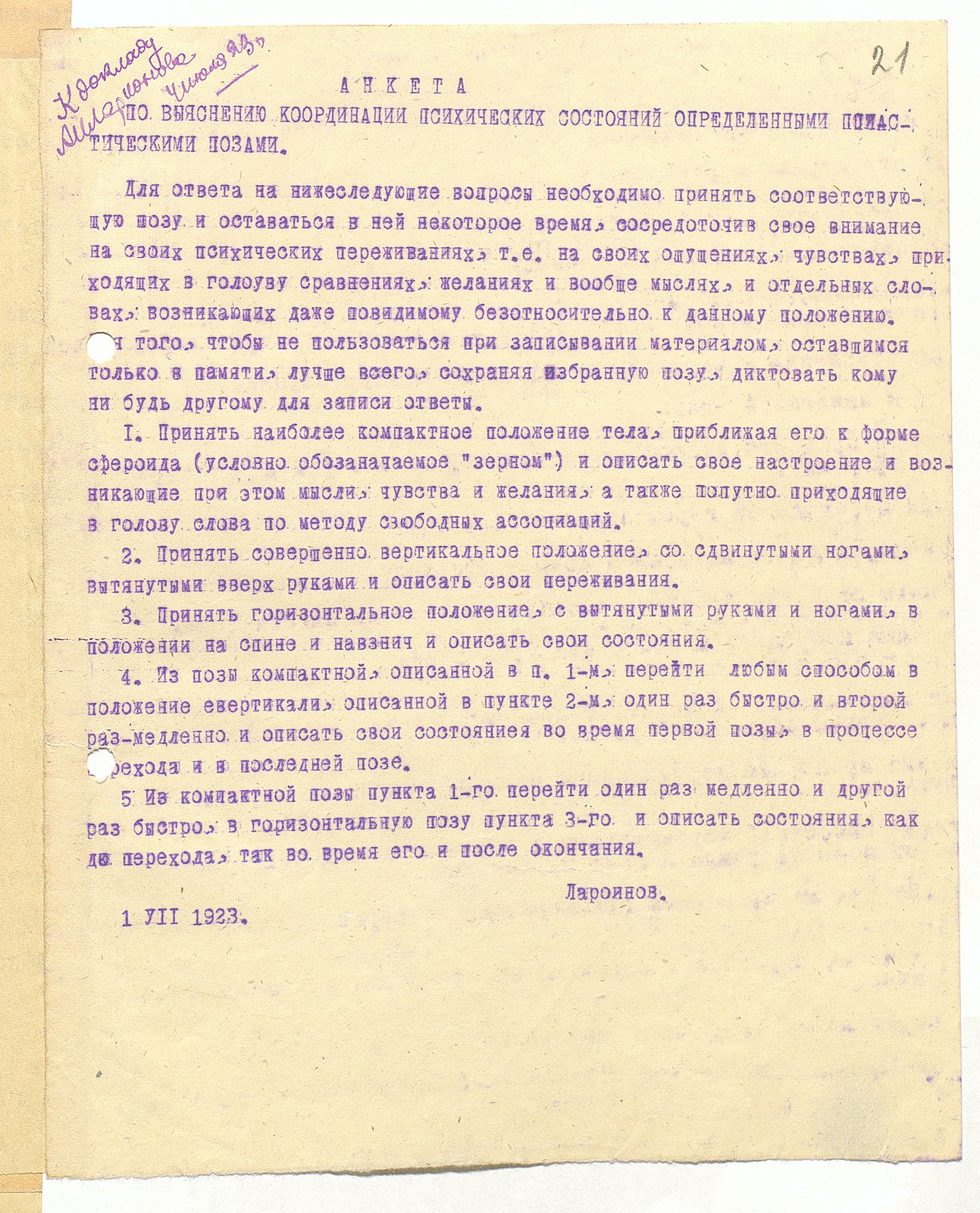

Alexander Larionov’s questionnaire for establishing the coordination of mental states with particular plastic poses, July 1, 1923

Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts (RGALI)

However, in light of the deepening ecological crisis, several articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are subject to criticism for their anthropocentric perspective. International law, which is based on the Christian moral code, reflects a hierarchy that values human life and comfort over the lives of other species that inhabit our planet. The pagan traditions of indigenous cultures, on the other hand, have proved to be more sustainable and efficient in their interactions with the environment than the Christian dogma of human dominance over nature practiced by the European colonizers. This observation (see Native Knowledge: What Ecologists Are Learning from Indigenous People by Jim Robbins and How the Dualism of Descartes Ruined Our Mental Health by James Barnes) was made possible by, among other things, the fact that the European critical thinking tradition became accessible to the representatives of colonized nations and their descendants. The agency acquired by the former objects of research has given us a broader perspective on questions of equal rights, and the fact that education in former colonies is dominated by European languages has helped the rapid proliferation of this knowledge. The critique of “universal values” has, therefore, partially resulted from global cultural decolonization.

In working with the archive of the Choreological Laboratory at the Russian Academy of Artistic Sciences (active from 1922 to 1930), we adhere to the principles of the decolonization of the imagination. We reactivate the material we study and put it into practice to turn it into an accessible source of knowledge. We believe that this approach is not only useful, but that it is necessary for the development of an independent assessment of taste in dance and its history and for identifying situations that are ethically and ecologically unacceptable.

We discovered that some of the artistic principles we often use in our work were not suitable for this research project. We had to renounce post-irony and the sabotage of structure. We do not wish to ignore the evolution of contemporary art in the twentieth century, nor the factors that gave birth to postmodern irony. However, in a world of contemporary art dominated by cold detachment and sarcasm, an attempt to treat the archive seriously and with the utmost respect seemed to be the most radical approach.