You can listen to the podcast on SoundCloud, Apple Podcast or Yandex.Music.

Thanks to artists, St. Petersburg’s rave culture of the 1990s was closely connected to what was going on in contemporary art and played an integral role. Club parties “that appeared during the period of ideological, social, and legal chaos” 1, were an ideal experimental platform for the development of a new visual culture, including performance, environmental design, large-scale installations, and media art. But most importantly, raves were a space of total freedom, where dance, music, and expanded consciousness became elements of a new ritual that united the younger generation. No wonder Timur Novikov compared raves with primitive shamanic rituals2, defining attending parties as a mystical, transformative experience.

In his book Shizorevoliutsiia, which explores St. Petersburg culture of the postwar period, artist and art critic Andrei Khlobystin called the first post-Soviet decade “the heroic era of Russian rave” and identified three stages of development: the squat period of the early 1990s, the “clubbing and large-scale parties in an urban environment” period of the middle half of the decade, and the period of open-airs near the Gulf of Finland, which ended the decade and linked the 1990s to the new decade.

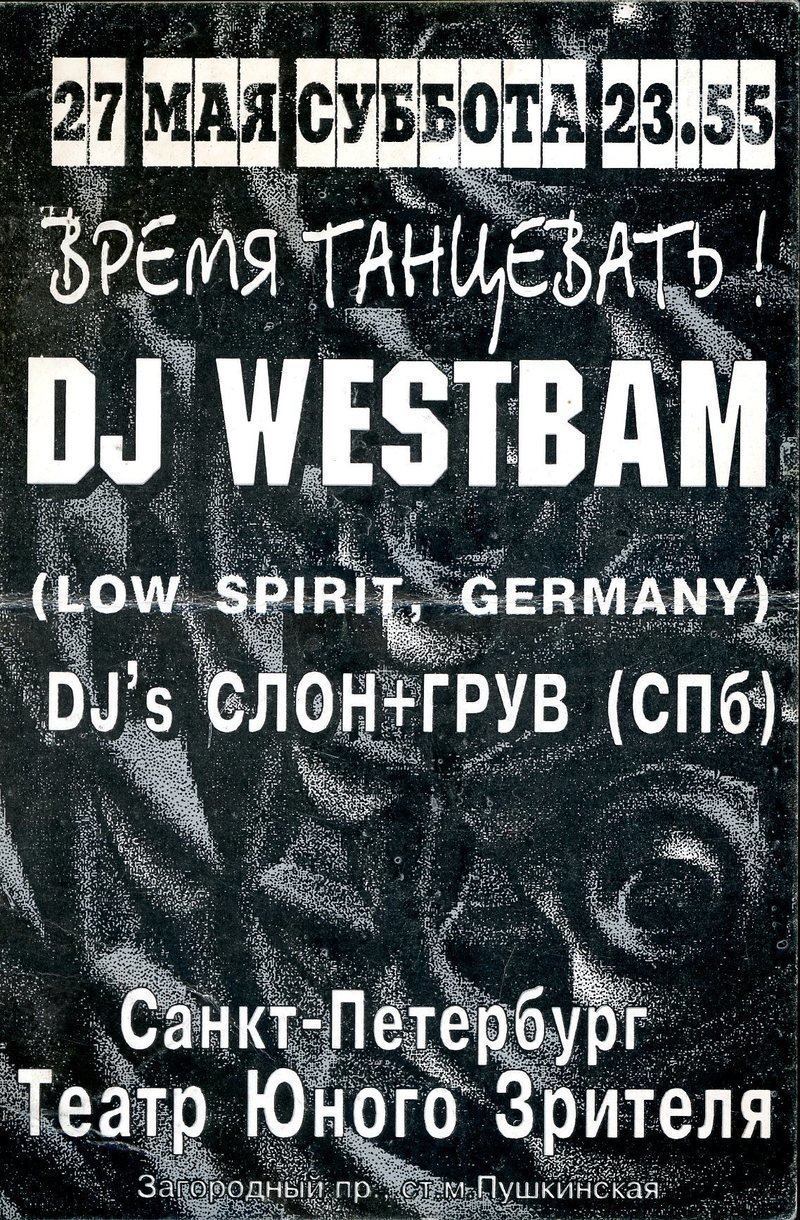

However, the history of the Russian rave movement—the“ravelution”—started somewhat earlier with the direct participation of Timur Novikov and other New Artists. The starting point was when Novikov met the German musician Maximilian Lenz (DJ WestBam) in Riga in 1987, when he, Sergey Kuryokhin, and the band Kino were taking part in a music festival. They quickly became friends and began cooperating creatively, as at that time WestBam’s hobby was remakes and remixes, which seemed to fit the theory of recomposition developed by Novikov and his friends. Novikov spent the next two years on the road, traveling around the United States and Europe, where he also immersed himself in club culture, becoming increasingly convinced that such parties were exactly what was lacking in his homeland.

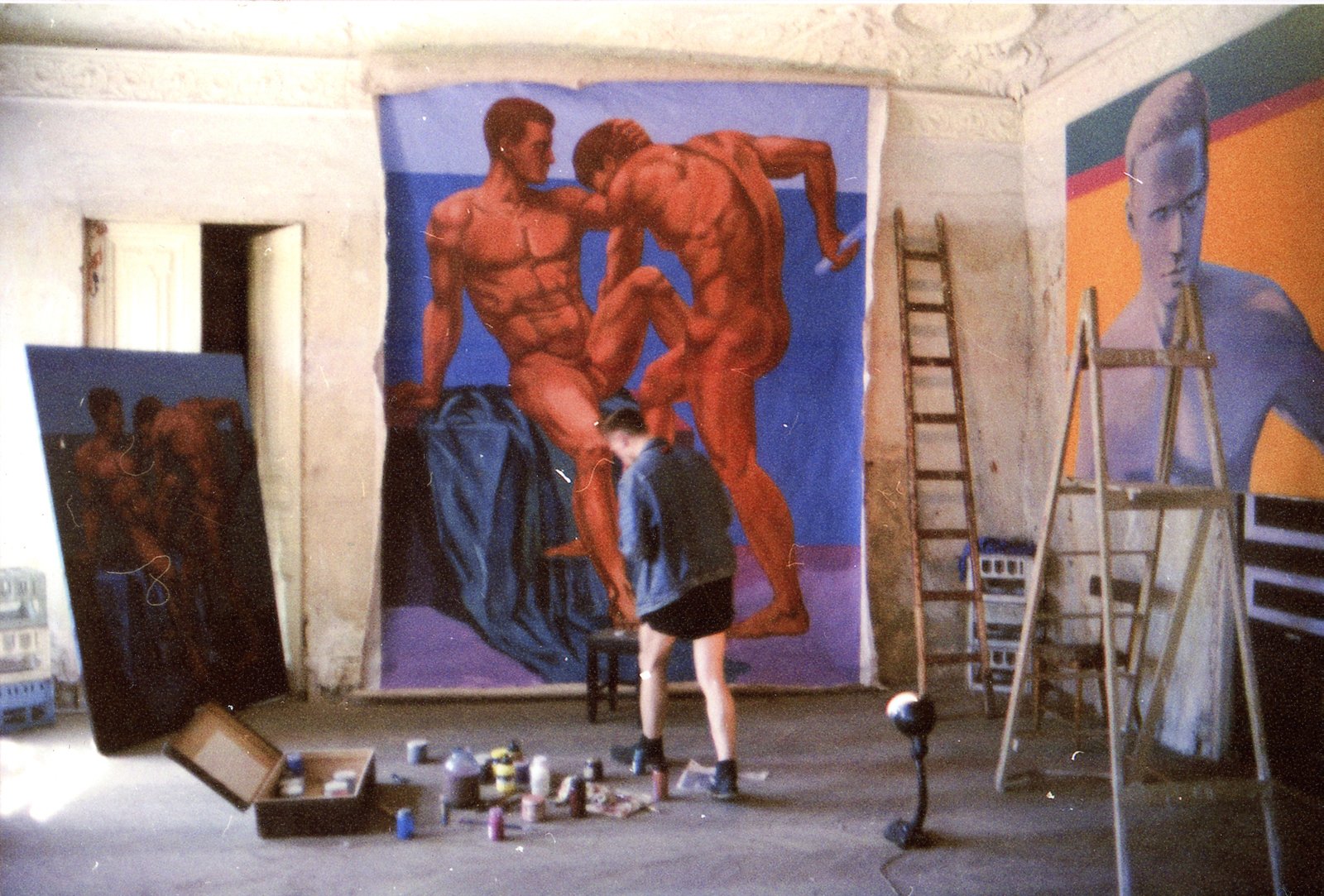

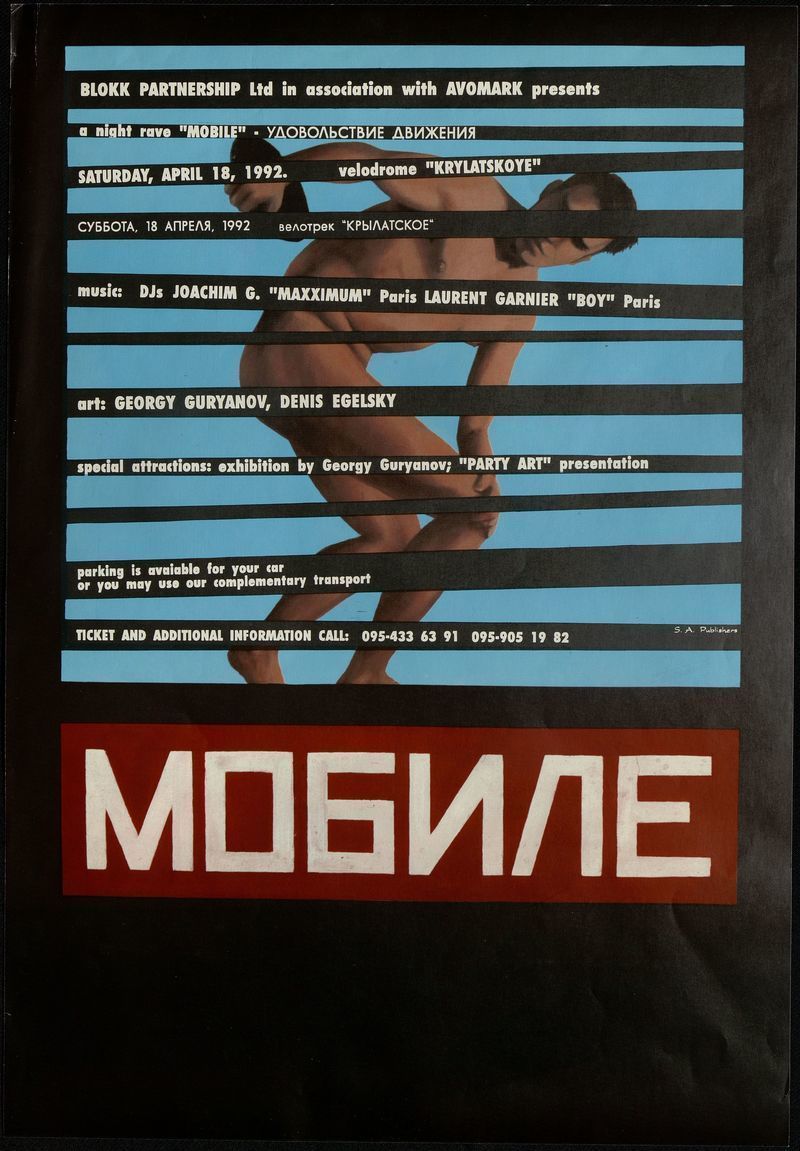

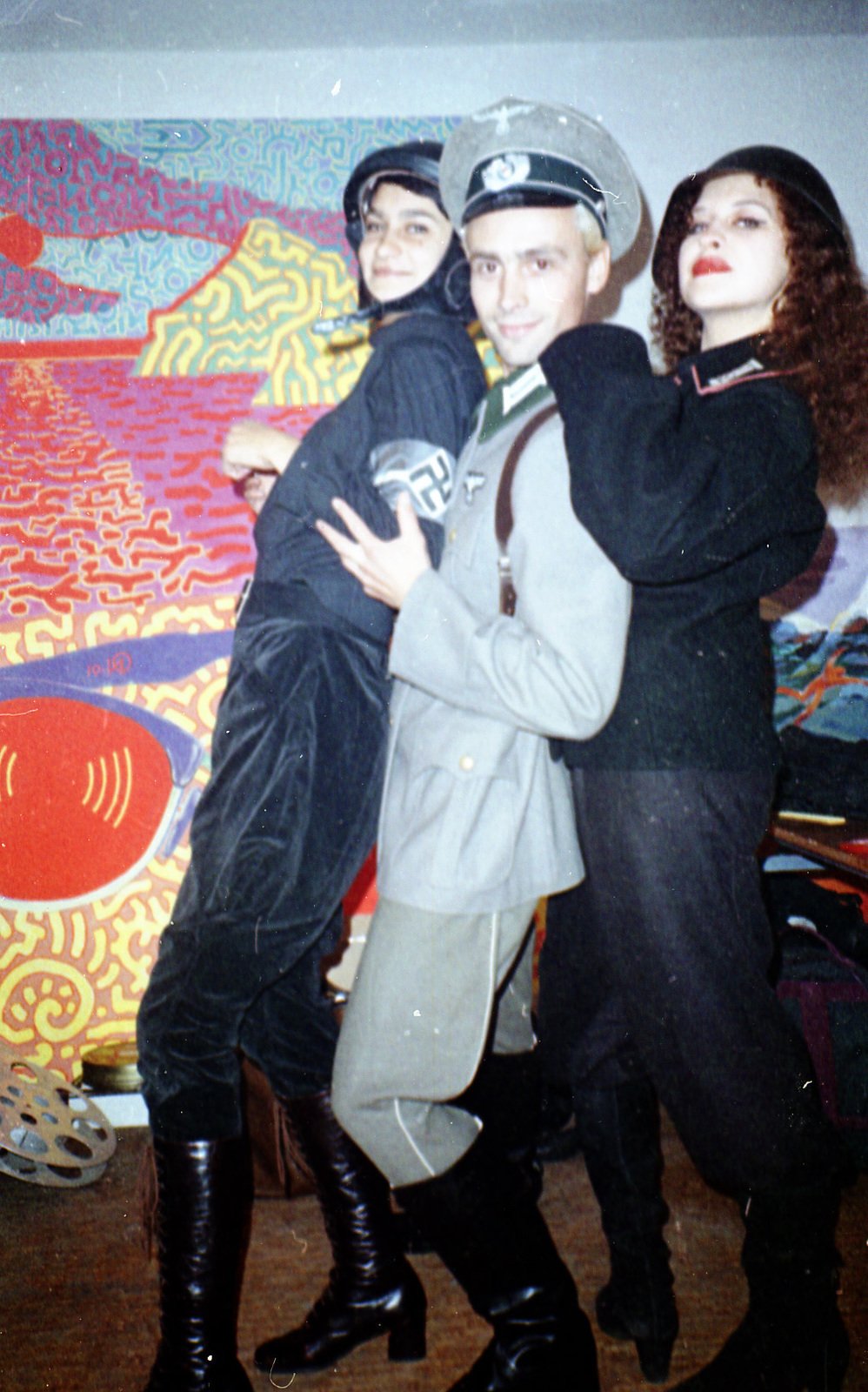

Returning to Leningrad, Novikov got down to business. The first party, organized by Novikov and Georgy Guryanov, took place in January 19903 in the House of Culture of Communication Workers on the Moika Embankment. At that time, there was no suitable equipment and no professional DJs in the city, so DJ Janis (Janis Krauklis) came from Riga in a car completely packed with the necessary equipment and records. The party’s program of events included the drag show The Voice of an Alternative Singer, one of the stars of which was Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe. This was the first time he had appeared in public in the image of the blonde femme fatale (it’s worth noting that the format of dancing plus drag shows is still standard in Russian gay clubs). The hall was decorated with large-format works by Novikov, Guryanov, and Denis Egelsky, made in a neoclassical manner, and Novikov would later call this party “the first art action” held by the New Academy of Fine Arts, which was founded in 1989.

Around the same time, the legendary underground club Dance Floor opened in Leningrad4, organized by brothers Andrey and Alexey Haas and Mikhail Vorontsov. The club was located in a large apartment on the third floor of the squat at 145 Fontanka, and was adjacent to the studios of Georgy Guryanov, Evgeny Kozlov, Juris Lesnik, Ivan Movsesyan, and other artists. There were regular parties at Dance Floor and they were carefully organized: the space was decorated with works by Alexey Haas, Guryanov, and Sergey Bugaev-Afrika, and for one of the parties (Guryanov-Party) they even produced white T-shirts with a silk-screen print of a naked male torso. One of these T-shirt is part of Garage Archive Collection in St. Petersburg. Dance Floor existed until summer 1992 and made dance parties incredibly popular among fashionable young people. Techno and house from closed squats flowed smoothly into the first "commercial" spaces. In 1991, parties began to take place at the Planetarium club, located in the Leningrad Planetarium, and in 1993 the Tunnel club opened, which for many years would be a raver mecca.

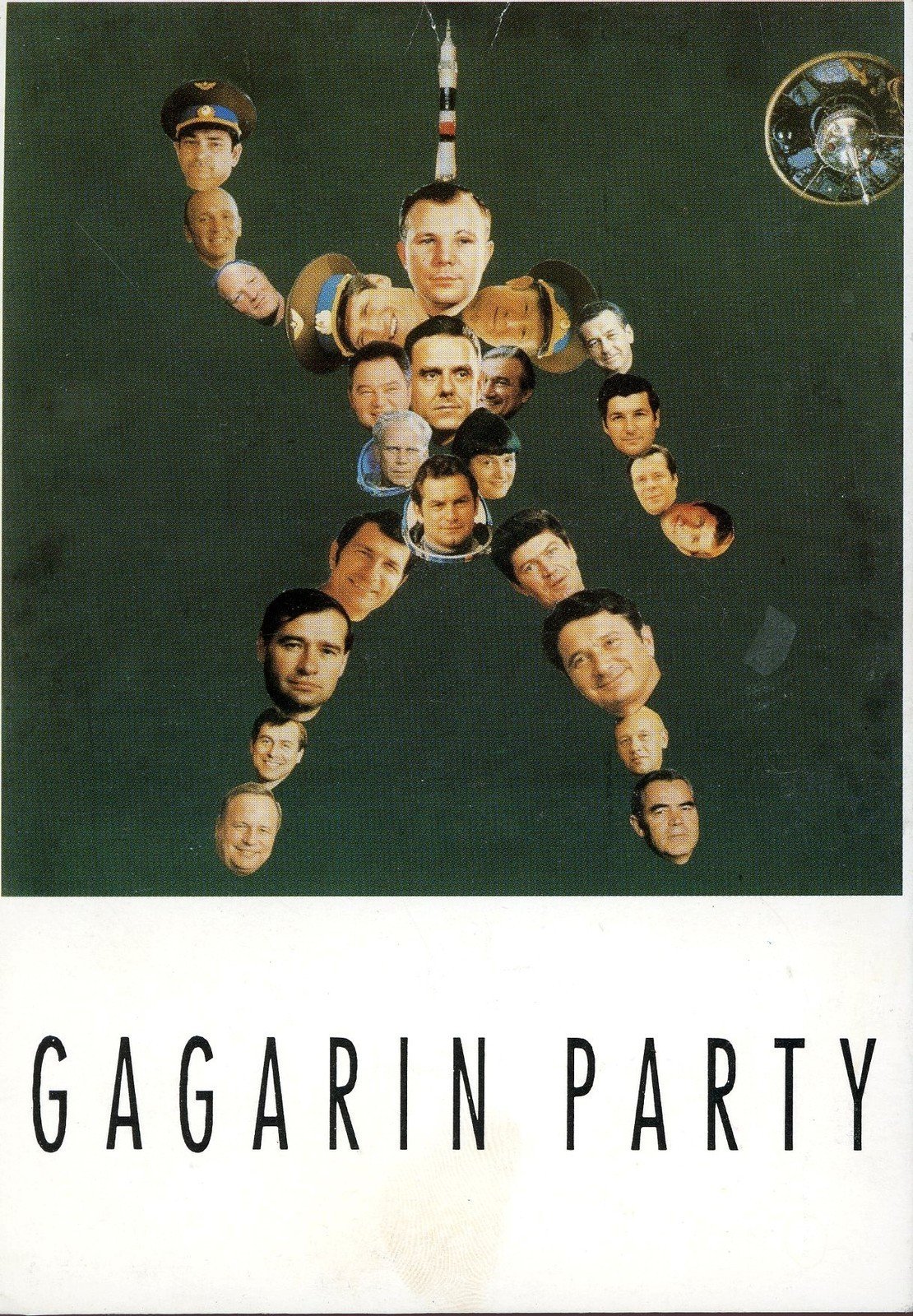

After Dance Floor closed, the team, realizing the demand for a new form of leisure and its commercial potential, organized a number of large-scale legal events, the most important of which were the Gagarin Party and Mobile raves, held in Moscow in 1991 and 1992. Unusual venues were chosen for both parties: the Cosmos Pavilion at VDNKh and the Cycling Track at Krylatskoe, respectively, which, of course, contributed to increased interest from the public.

St. Petersburg was not far behind. In 1992, raves began to expand into public spaces. Andrei Khlobystin noted an interesting feature of St. Petersburg nightlife in the 1990s, which involved a desire to rethink Soviet heritage by entering its "sacred" spaces. Due to the financial crisis, numerous museums and cultural heritage sites survived by renting out premises for various events. Accordingly, large-scale parties were held in the Artillery Museum, the pavilions of Lennauchfilm, the Circus on Fontanka, the Young Spectator’s Theater, and even in a swimming pool5, where a series of Aquadelika parties took place. Another St. Petersburg phenomenon of the first half of the 1990s was parties in palaces, the best-known of which were in the Beloselsky-Belozersky Palace and the mansion of Matilda Kseshinskaya.

By the mid-1990s, the popularity of parties was so great that raves became commercial projects created not only out of love for electronic music and for a narrow circle of partygoers but also as a way to earn good money. The production company Kontrfors appeared in St. Petersburg and launched the large-scale festivals Eastern Blow and Ravemontage, which attracted thousands of people. In parallel, the mood of the main stars of St. Petersburg clubland, the artists of the New Academy, changed sharply. In place of a bohemian way of life with an endless round of parties there was now “the new seriousness,” which proposed a focus on traditional values. As a result, the artists left the club scene. Mass parties in the center of the city or in important locations were replaced by private DIY events in the countryside or on the outskirts of the city.

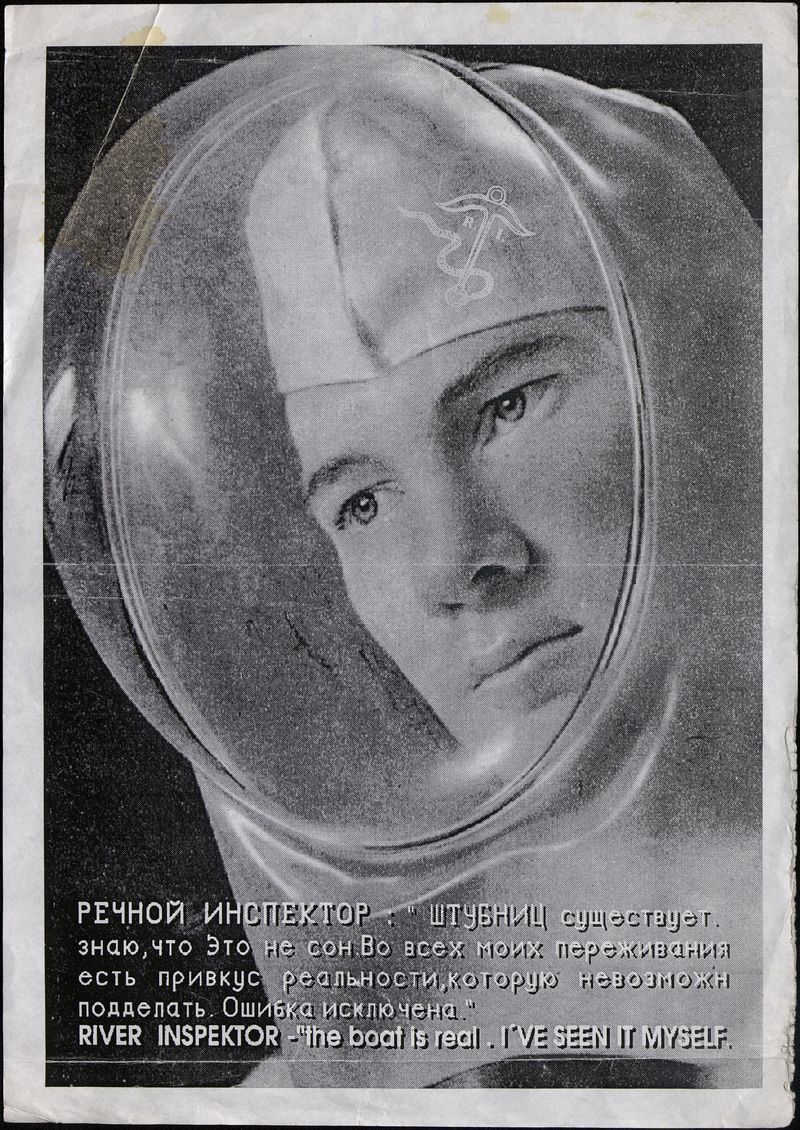

The Illegal Picnic was the first “new format” party, held in July 1996 in the ruins of a nineteenth-century military fort adjacent to the dam connecting St. Petersburg and Kronstadt. The flyer promised “new entertainment,” “100% underground,” and free admission. The rave was organized by artists from the group Klub Rechnikov, using the brand of the independent news agency MESSMEDIA and with the support of the Berlin sound system INTERFLUG GALAKTIKA.

The “Rechniki” were famous St. Petersburg squatters, students of the New Academy and active participants of the city’s art life. They organized this party for members only, launching a trend for open-air events. The atmosphere was created by the industrial landscape, the placing of the DJ console on the cabins of army trucks welded together, and video projections integrated into the natural landscape. The headliner was the London DJ Gravity Girl, who was resident on the ship Stubnitz. The Russian side was represented by Massash, Demidov, BOOMER, Elephant, Lena Popova, and Angela. Despite strict secrecy, around 500 people attended the Illegal Picnic and the magazine Ptyuch dedicated a page to it, describing the event as one of the best parties of the year6.

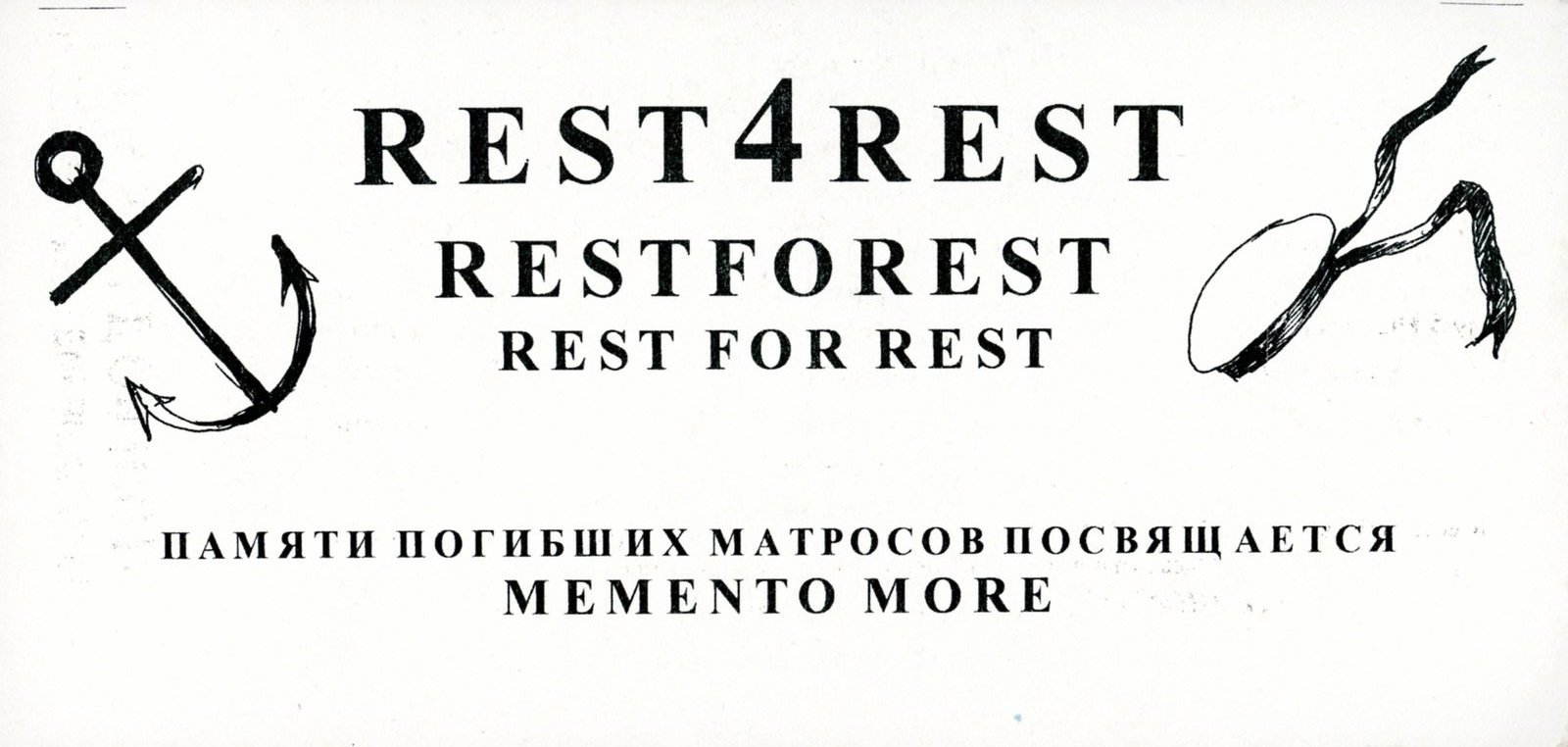

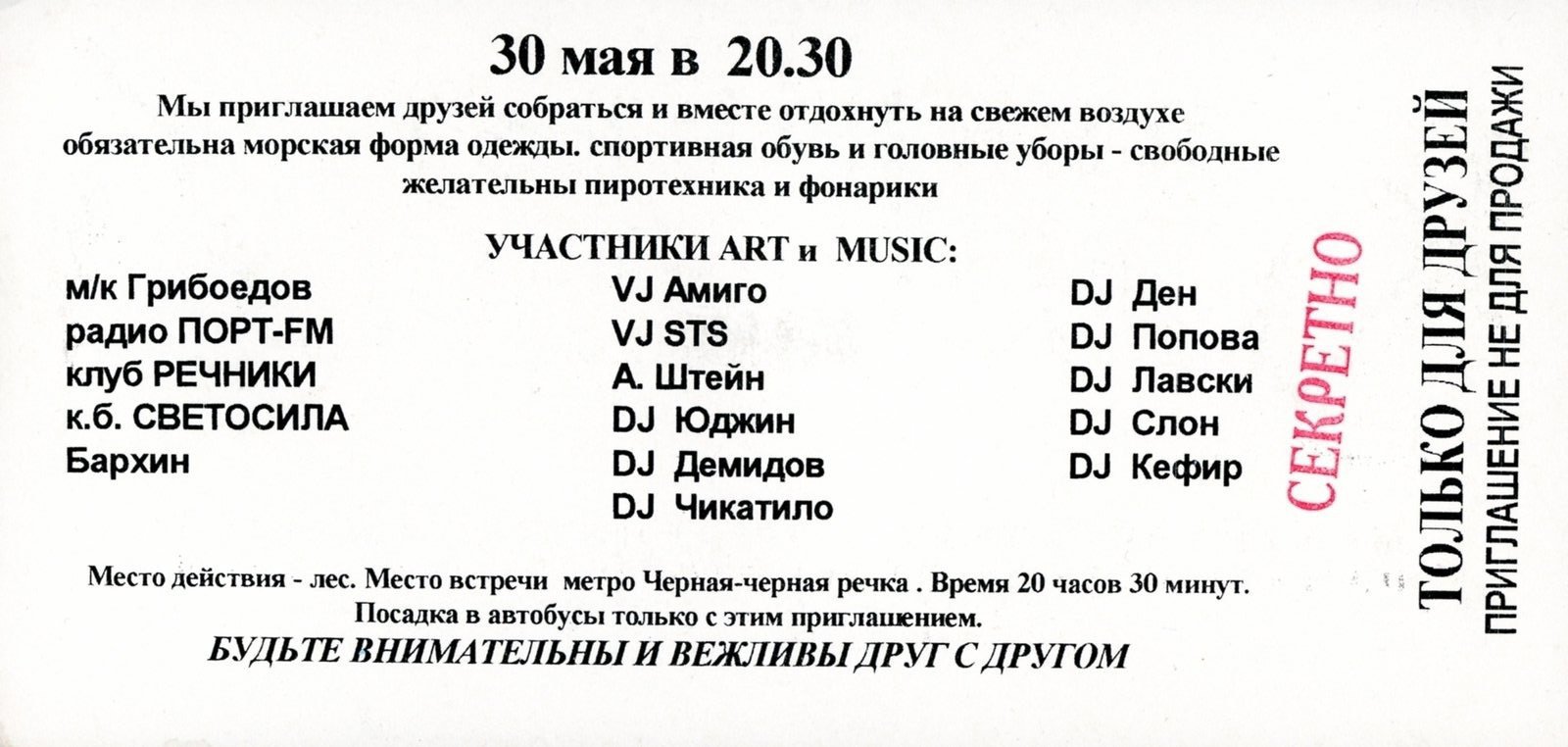

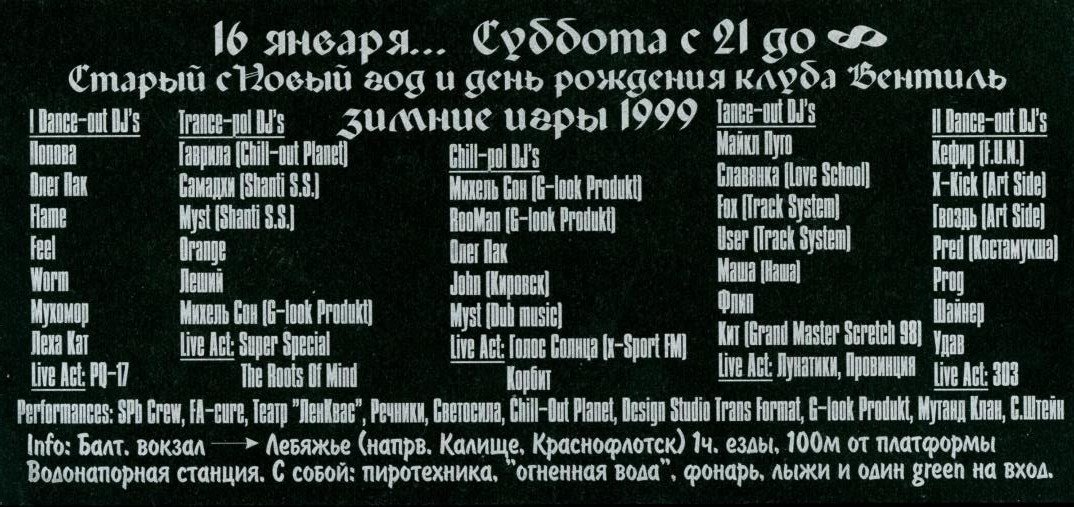

Up to the end of the 1990s the “Rechniki” held other parties in the countryside, including the Rest4Rest forest rave for friends (1998). The invitation was marked “secret,” and instead of providing a location only the time and initial meeting point were mentioned. They also celebrated Old New Year and the birthday of Valve club at the water station in Lebyazhye. The latter two events had a strong line-up and an art program organized by the “Rechniki” with the design company Svetosila7, Alexander Shein, and other media artists.

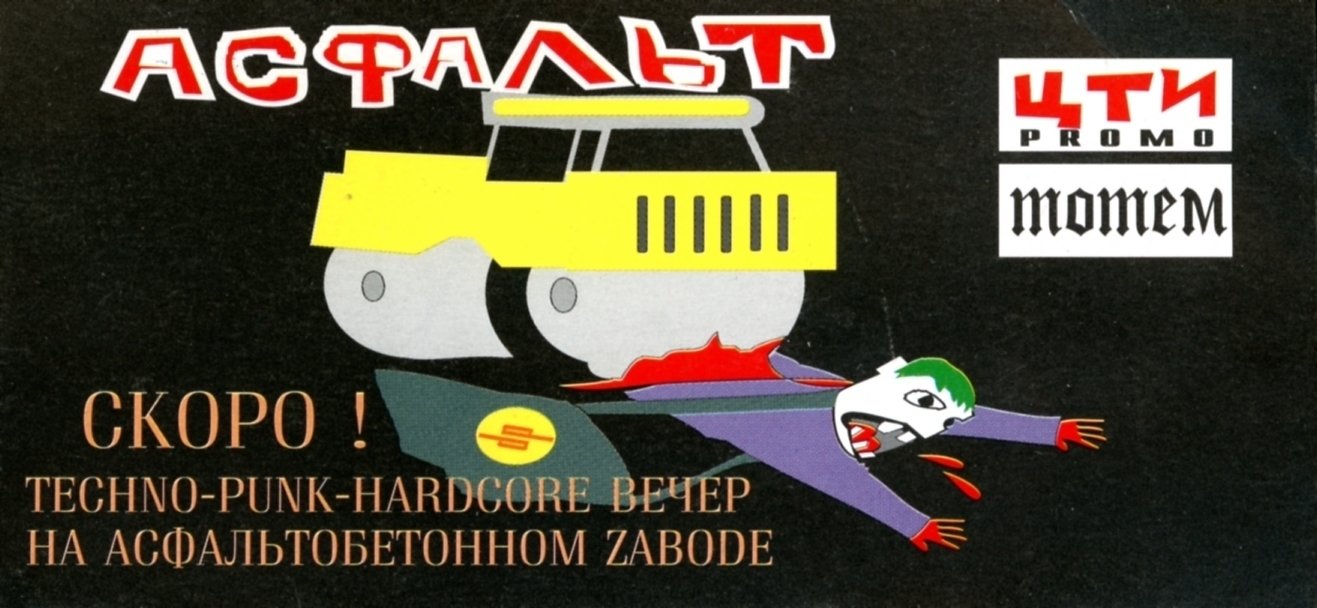

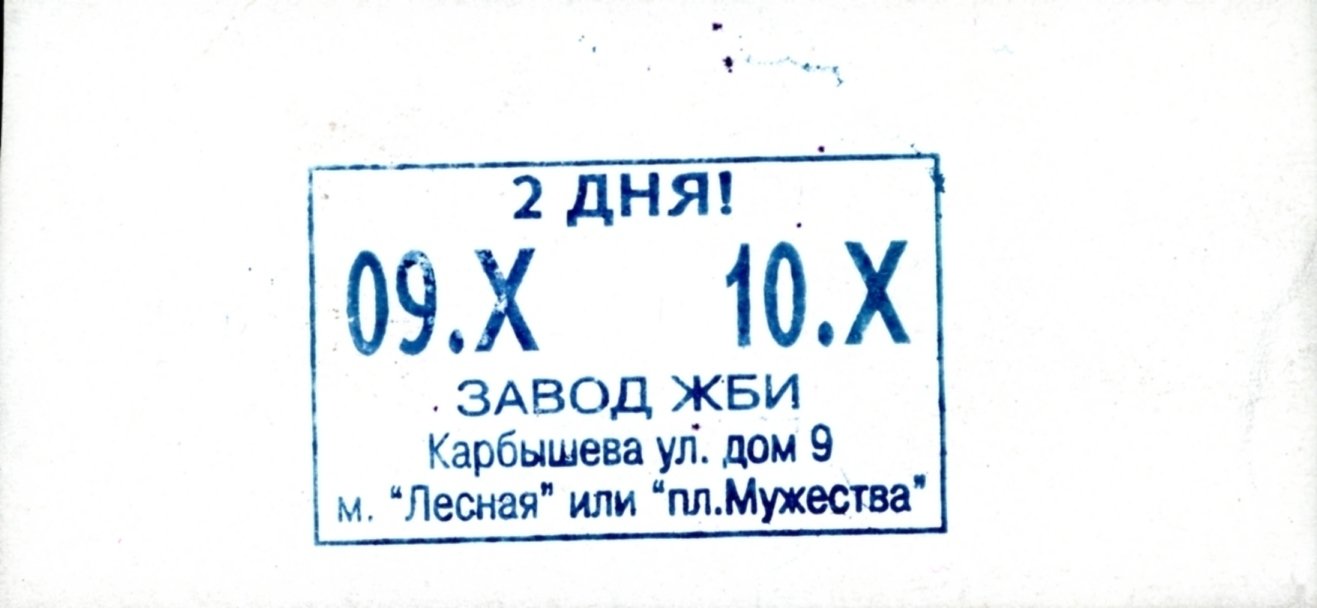

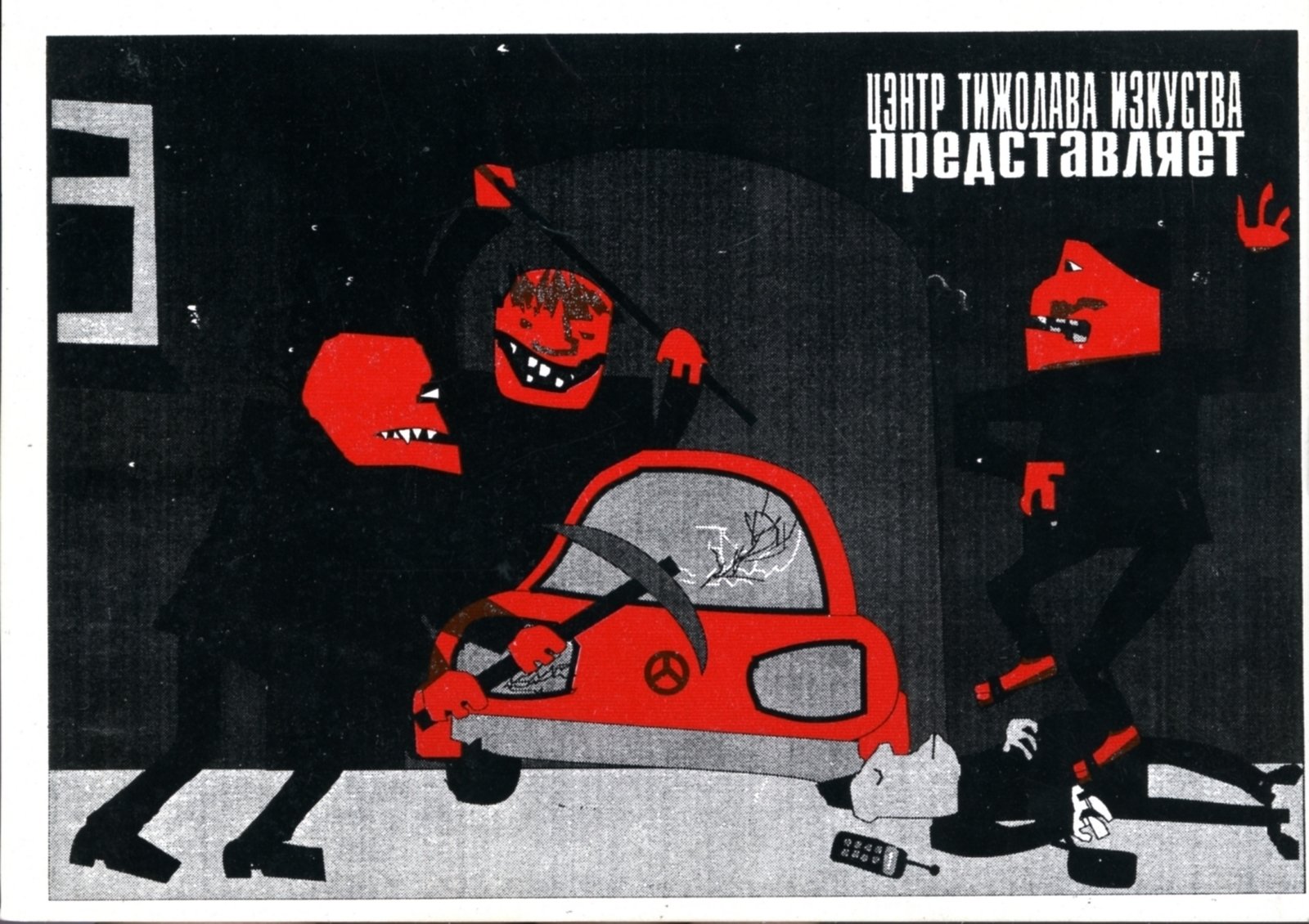

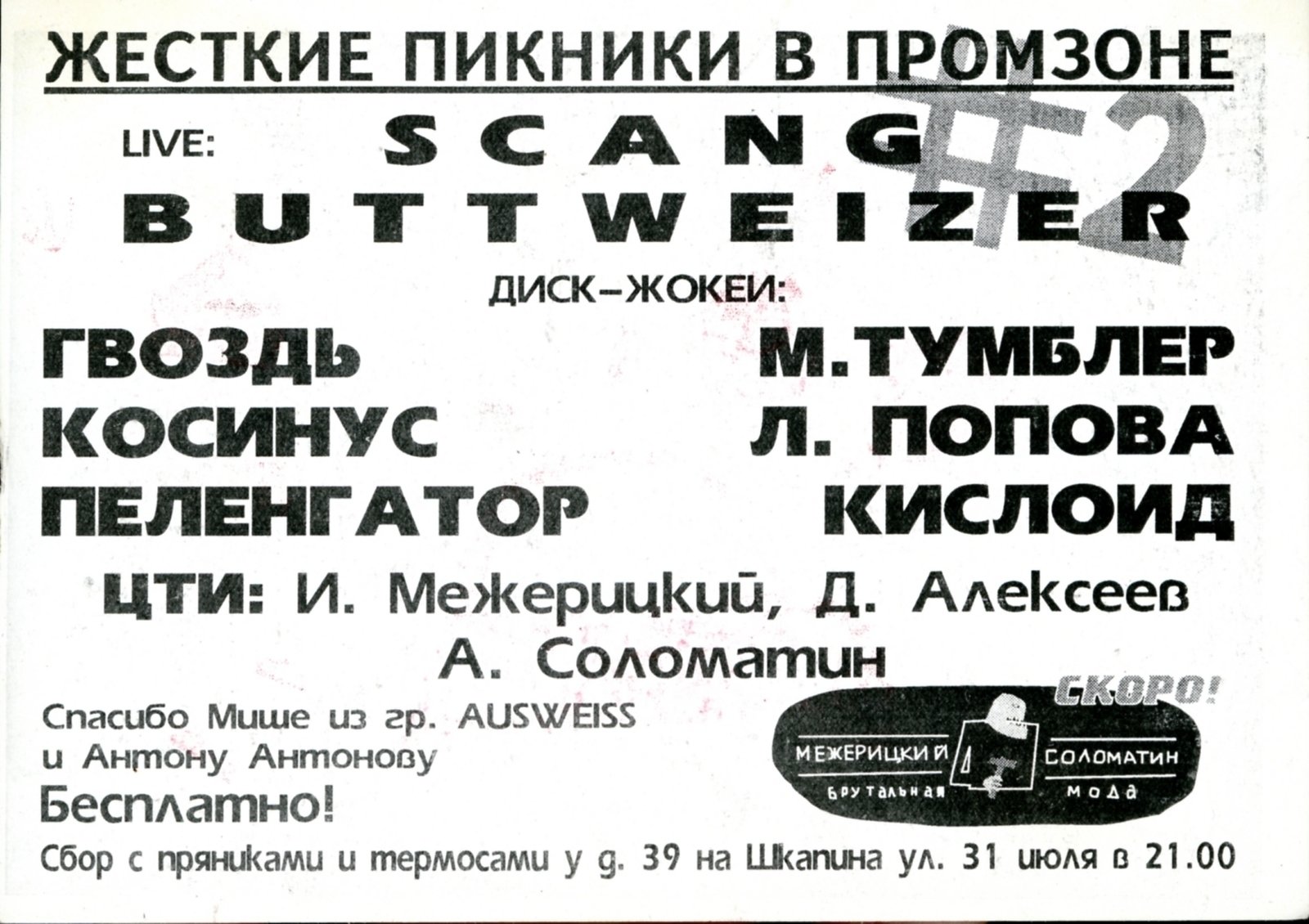

The trend for closed parties was continued by the artists of the association Tsentr Tizholava Izkustva. While some partygoers preferred to go to the suburbs, “brutalists” Igor Mezheritsky and Artemy Solomatin enjoyed the industrial aesthetics of remote areas of St. Petersburg. With free entrance, heavy sound, and the gloomy atmosphere of the industrial zone, TTI events were given appropriate names: frightening “techno-punk-hardcore” evenings or depressing “hard picnics.” The Asphalt techno-hardcore party was held at the Reinforced Concrete Products Factory, located on the border of a residential area and an industrial zone. The flyer for the event Cruel Picnics in the Industrial Zone invited people to visit a secret location for free, with the meeting point at 39 Shkapina Street, behind the Baltic railway station. Techno DJ and “picnic” participant Lena Popova recalls a certain “party on the rails” organized by Solomatin, but there are no archival documents about this event.

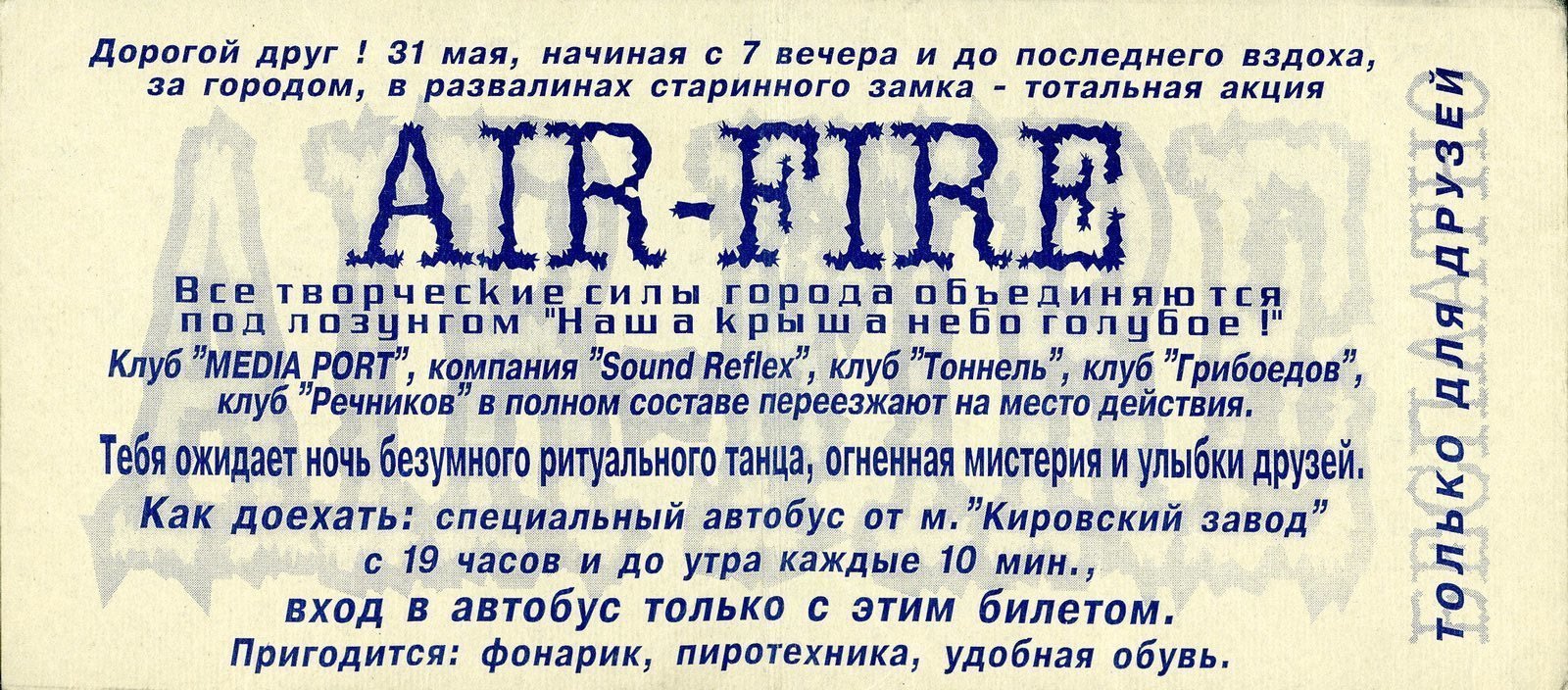

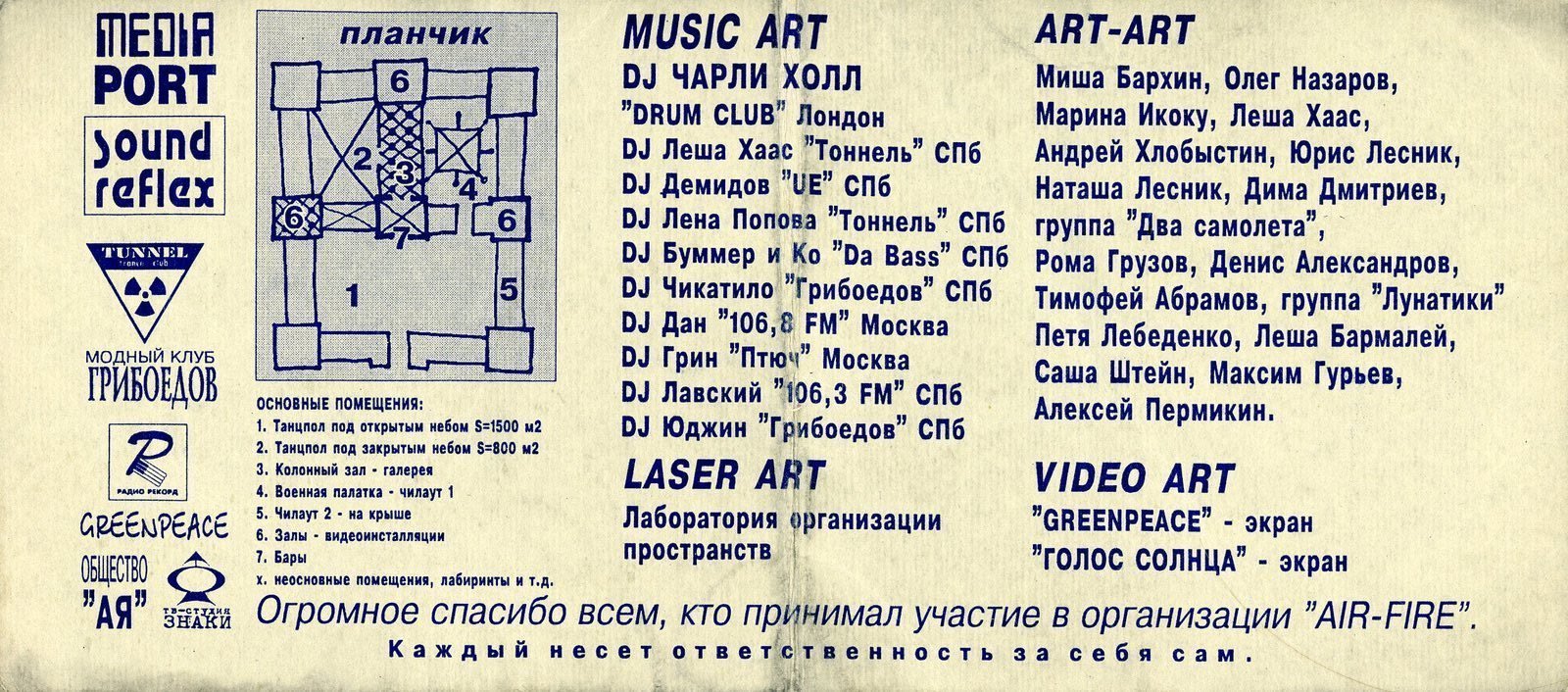

Another famous open-air event was AIR-FIRE8 which took place in May 1997 at the Znamenka estate, located between Strelna and Peterhof and was part of the promotional campaign for the Port club (which was designed by the “Rechniki”). Unlike the Illegal Picnic, this party was the result of the consolidation of all the club people in St. Petersburg, and brought together several thousand ravers. The dancers were placed inside and outside the ruined stables, which had been occupied by the organizers under the pretext of making a film. The party included an exhibition of objects and media art by Klub Rechnikov, Andrei Khlobystin, Juris Lesnik, Alexander Shein, and other artists. The rave at Znamenka was attended by the bohemian crowd; even art critic Ivan Dmitrievich Chechot was seen in the crowd. The organizers were not afraid of drawing the attention of the police, despite the large number of guests, as the date of the party coincided with a visit to St. Petersburg by government officials and all law enforcement was pulled into the city center. Nevertheless, the smooth course of the event was disrupted. Toward morning, a police car drove right into the courtyard of the ruined building, calling on the organizers of the event to come to the station “for clarification.” None of the dancers reacted, probably because a car with flashing lights slowly crawling through the crowd, with the siren merging with the music, was perceived as a performance.

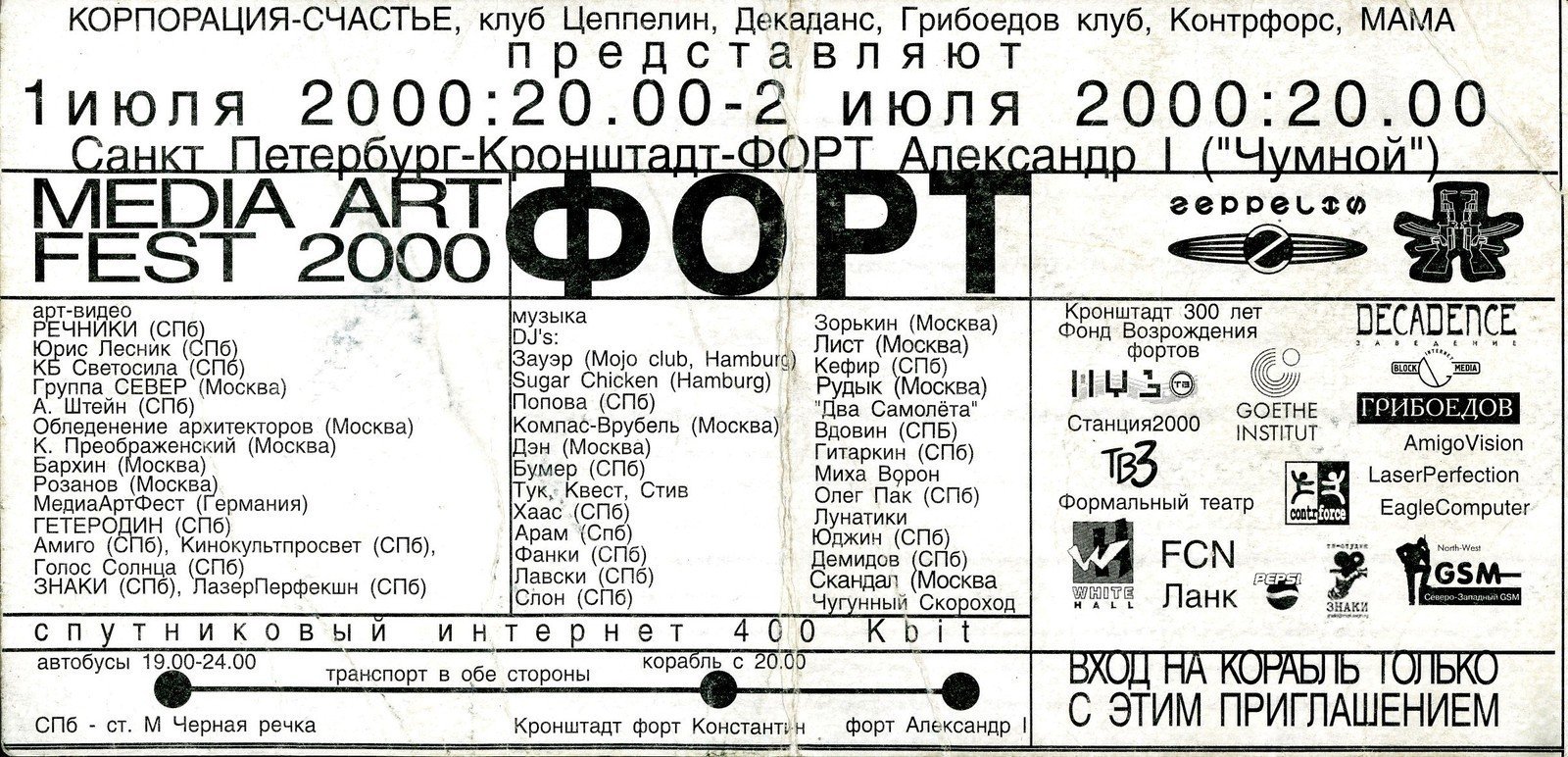

The Znamenka party revealed the potential of suburban locations and, largely thanks to this experience, in 2000 the first of four open-air parties took place at the Kronstadt forts, with which Andrei Khlobystin closed the chronology of the “heroic era of Russian rave.”

1. A. Khlobystin, Shizorevoliutsiia (St.Petersburg: Borey Art, 2017), p. 291.

2. “Timur Novikov: ‘Kak ya pridumal reiv’,” ОМ, 3, 1996, p. 69.

3. Various dates are given for this party. In his autobiography, Timur Novikov suggests 1989, while Andrei Khlobystin and a number of other sources date it to 1990.

4. In addition to Dance Floor, in the early 1990s there was another club in a squat in St. Petersburg, where parties were regularly held. It was called Obvody and was located in a building at 217 Obvodny Canal that had been taken over by artists.

5. The LIIZHTA pool.

6. “Peterburg: Novyi vzyrv klubnogo ekstaza,” Ptyuch, 10, 1996, p. 20.

7. A creative association founded by the artists artists Sergey Sosnin, Sergey Gusev, and Roman Yadykin in 1997.

8. In some texts and memoirs this party is called Air Fair. We have used the name AIR-FIRE, which corresponds to the invitation.