Exhibitions on the bridge

You can listen to the podcast on SoundCloud, Apple Podcast or Yandex.Music.

“On one wing of the drawbridge, paintings by Leningrad artists were exhibited for several hours under the searchlights. From a distance, they looked like postage stamps on black asphalt. An elegant bohemian was ceremoniously strolling along the embankment, bowing with special friendliness, slightly excited by the night air of the outgoing summer. This was the most beautiful exhibition of contemporary artists that I have ever seen. Maybe because the artists, or rather, their paintings, played a very secondary role in it.”1.

The event that Avdotya Smirnova describes is not a fiction. She is referring to the second exhibition on Palace Bridge, organized by the artist Ivan Movsesyan. From 1990 to 1992 such contemporary art exhibitions in the “classical landscape” of Leningrad/St. Petersburg were held each summer.

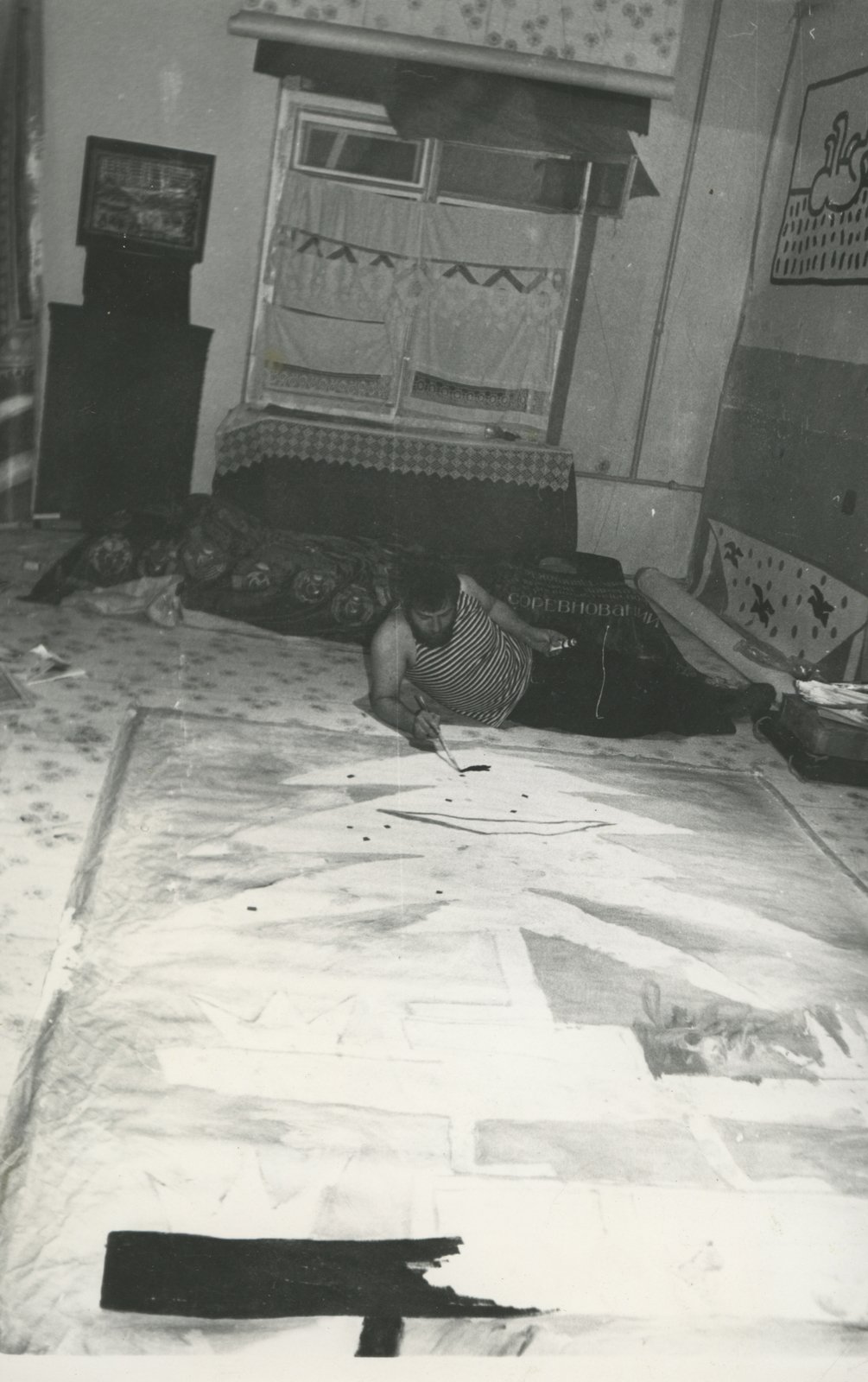

Movsesyan, like many young people at the time, was interested in underground art. After he met Yuris Lesnik and Georgy Guryuanov he became part of the squat at 145 Fontanka Embankment. (E-E) Evgeny Kozlov had his studio in the same building. He was one of the founders of the New Artists, who played an important role in the exhibitions on the bridge. In 1990, Kozlov began work on the project 2 × 3 Meters Collection. He managed to find paint and large-format canvases and invited artist friends to his studio, suggesting they create works. Oleg Kotelnikov, Ivan Sotnikov, and Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe were the first artists in the collection.2 Among the New Artists it was customary to work fast, and pictures could appear during one or two sessions. The first exhibition on Palace Bridge included many of these works. The rapidly growing collection of large works may have inspired Movsesyan to create a spectacular exhibition, or, on the contrary, he found in them the materials suitable for his concept. Either way, the concept appeared: the works of underground artists were supposed to take off in the urban landscape, right in front of the Hermitage.

By July 22, 1990, the artists had reached agreement with the city administration. Enlisting the support of mayor Anatoly Sobchak, they received permission from Mostotrest [the bridge authority], the police, and other organizations responsible for the urban space3. On the appointed day, thanks to the efforts of the participants and their friends, the exhibition was mounted, with the works fixed to the bridge using cables. The group acted quickly: only the time interval between the traffic stopping and the bridge opening was available for installation, and at 1 am the exhibition opened. Art critic Hannelore Fobo recalled: “In the 1990s it was very interesting in Russia because in the circles in which I was lucky enough to mix there was a very free attitude to everything. […] Exhibitions on the bridges. Can you imagine what kind of structure that would involve now, at least financially? Then someone just managed to sort it out with someone else. […] The heady feeling of ‘I want to and I can’ was a beautiful illusion of life.”4.

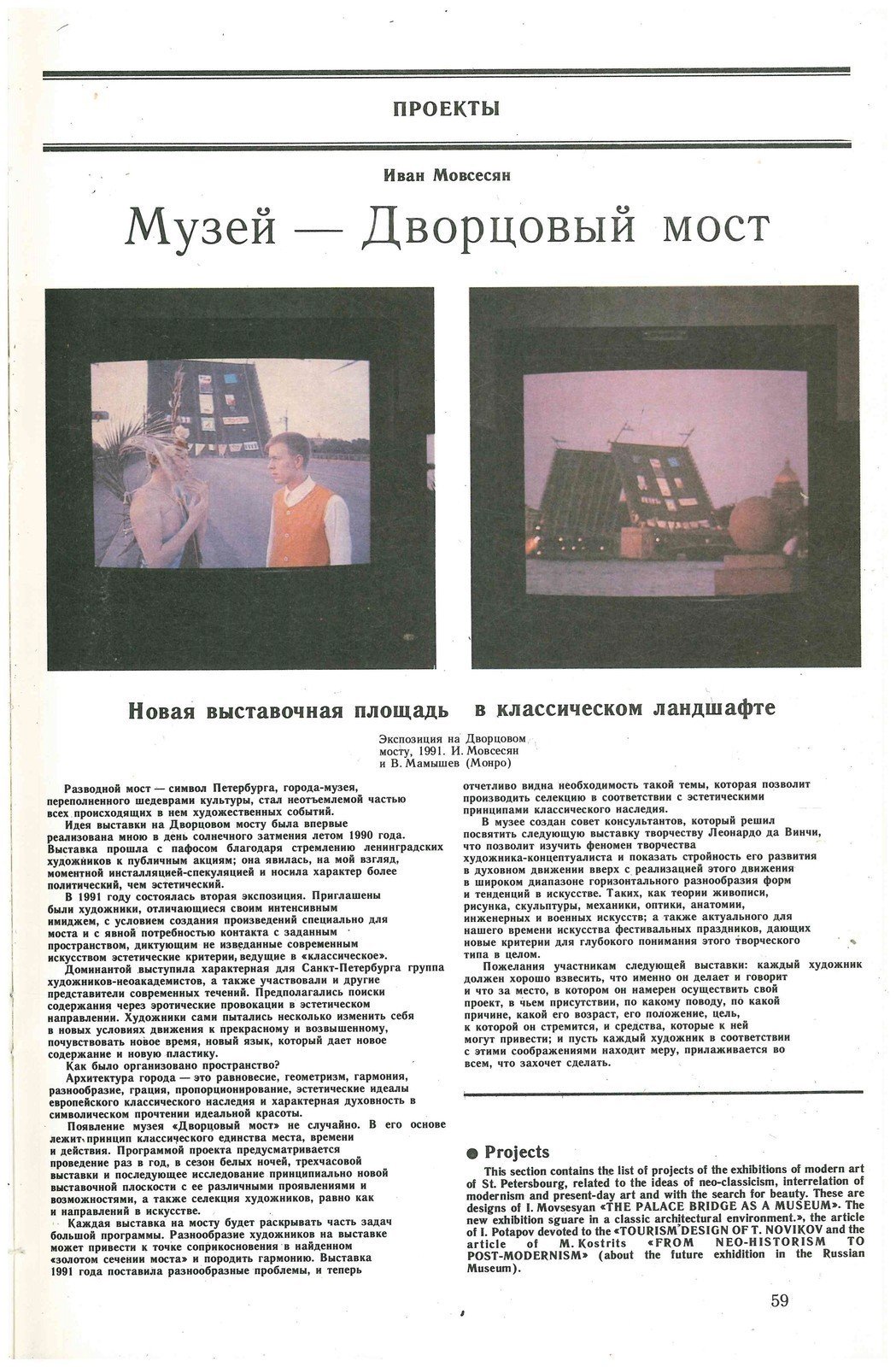

This event showed that there were new opportunities for artists. Avdotya Smirnova, who caustically noted that the paintings at these exhibitions “played a secondary role,” was right: the works, linked together and raised by the bridge, could hardly be clearly seen. The main event of these actions was the city’s compliance check. Timur Novikov, Georgy Guryanov, (Е-Е) Evgeny Kozlov, and other participants could show their works in other countries during perestroika, but in Leningrad the main sites for their art were recreation centers, expocenters, and squats. The political, economic, and cultural changes that defined the 1990s “opened up” for underground artists not only the urban space but also palaces and museums. Movsesyan’s exhibition project also acquired institutional status. In 1992, with the support of the St. Petersburg society A–Z, he registered the Palace Bridge Museum. However, only one exhibition was held using this name: the last in this series, which was dedicated to Leonardo da Vinci.

From the point of view of research into the art community, the exhibitions on the bridge were an important chapter. In the late 1980s, Timur Novikov, who was one of the leaders of the New Artists, began working on a neo-academic program that insisted on the return of the concept of beauty to art. Soon, a group of artists formed around him, ready to join in this game. Ivan Movsesyan was among them. In the text of 1992, he wrote that all of the participants of the second exhibition on Palace Bridge were ready to work with a city that sets “aesthetic criteria leading to the ‘classical’.”5 In fact, there were more “wild," neo-expressionist works in the spirit of the New Artists in the exhibition than there were works claiming to be “beautiful.” The spirit of the New Academy at the second exhibition was conveyed only by Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe, who attended as a Palace Bridge cherub. He made a pseudo-antique tunic from a satin tablecloth and wings from dried palm branches found on a garbage dump, and wore a plastic funeral wreath on is head.6 The video with his antics taking place against the background of the porticos of St. Petersburg became the basis of the film Exotic Classic by Yuris Lesnik. Later, Novikov and the artists in his circle turned with great reverence toward the art of the past and finally dissociated themselves from those who continued working in the tradition of the New Artists of the 1980s. However, the exhibitions on Palace Bridge captured the state of artistic life in St. Petersburg at a time when these different aesthetic programs could coexist in a single action.

1. A. Smirnova “Skromnoe ocharovanie Leningrada,” Dekorativnoe iskusstvo, 7-8, 1992, p. 50.

2. [Hannelore Fobo], The Kozlov Collection “2×3m” on Palace Bridge, St. Petersburg, http://www.e-e.eu/Exhibition-Palace-Bridge/index1.html.

3. Matveeva, “Mesta sily neofitsial’nogo iskusstva Leningrada–Peterburga. Chast’ 8. Vystavki na Dvortsovom mostu, 1990–1992,” ArtGuide, https://artguide.com/posts/1018.

4. “Interv’iu Ekateriny Sarvirovskoi s Khannelore Fobo,” Readymag, https://readymag.com/softenjoyment/1820055/112.

5. Ivan Movsesyan, “Muzei—Dvortsovyu most. Novaya vystavochnaia ploshchad’ v klassicheskom landshafte,” Dekorativnoe iskusstvo, 7-8, 1992, p. 59.

6. Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe, ‘Iz pis’ma Andreiu Kovalevu,” WAM 28/29 Rossiiskii aktsionizm 1990–2000 (Moscow: WAM, 2007), p. 55.