You can listen to the podcast on SoundCloud, Apple Podcast or Yandex.Music.

Today, in a building constructed on Universitetskaya Embankment in the eighteenth century especially for the Imperial Academy of Arts, there is a higher education institution training artists, architects, and art critics. For many years the Ilya Repin St. Petersburg Academy of Arts, as the university is called today, has been a mainstay of traditional art education, and contemporary art practices are still regarded with suspicion. Even so, this academic institution occasionally been an experimental platform for those trying to rethink artistic canons.

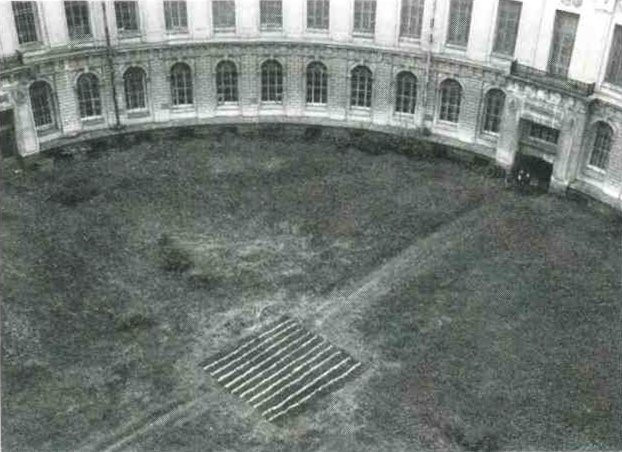

One such intervention was the action Malevich’s Garden, organized by the art group Tut-i-Tam in May 1992. The location was the round courtyard of the academy, which occupies the central part of the building. Today, this space looks severe and almost lifeless: it is paved with gray tiles, in the center there is a monument to one of the founders of academic art education in the Russian Empire, Count Ivan Ivanovich Shuvalov, designed by Zurab Tsereteli. In the 1990s, the courtyard was made of earth, overgrown with bushes and grass. The authors of the action decided that this huge green area in the heart of the academy would be ideal for sowing the “seeds of the avant-garde.” And so, Malevich’s Garden appeared, a square bed of carrots. One of the participants, artist Ivan Govorkov, described the event as follows: “To dig into the round courtyard of the orthodox Academy of Arts the Black Square of suprematism, plant seeds... and wait for the form that sprouted in the plane to be born and eaten in real life.”1.

The local history of art was actively reconsidered during perestroika and in the early 1990s, with the Russian avant-garde being widely acknowledged. The appearance of Malevich’s Garden in an institution that had not yet accepted these changes showed that this process was irreversible, just like the growth of carrots. Plus, the authors of the intervention were all connected to the Academy, which is where they met. Accordingly, Malevich’s Garden was not simply an ironic gesture of invading the territory of traditional art but also a way of reflecting on their own artistic biography.

The organizers of the Tut-I-Tam, art critic Nadezhda Burkeeva and artist Alexei Kostroma, graduated in the 1980s, and in the early 1990s decided to work in field of contemporary art. One aspect of their work was actions in public spaces, during which they played on the “picture postcard” emblems of Leningrad/St. Petersburg. For example, as Tut-I-Tam they launched small copies of the Alexander Column and the Bronze Horseman, made from balloons, into the sky. From 1994, when Kostroma began to develop the concept Plumage of Names and Symbols, the artists organized actions in which the cannon of the Peter and Paul Fortress, a replica of the 18th-century schooner St. Peter, and other city sights were covered with white feathers. The work at the Academy of Arts was also part of their strategy to rethink those places that are important for the “St. Petersburg legend.”

There were two permanent members of Tut-I-Tam, but many other artists cooperated with them. The co-authors of Malevich’s Garden, artists Elena Gubanova and Ivan Govorkov, also graduated had an academic art education and took up the practice of contemporary art in the early 1990s. For all participants the action, in which tradition and the avant-garde literally became the ground for a new work, was also a metaphor for their own transformation into contemporary artists.

By fall the harvest had ripened. Even though Malevich's Garden grew in view of the entire Academy, it did not attract much attention. The event was noticed only when the dug-up vegetables were presented at an exhibition at the Russian Ethnographic Museum, which was the final stage of the action. Before the opening, the participants symbolically crossed the Palace Bridge carrying two huge papier-mâché carrots on their shoulders. The procession was a reminder of the provocative walk of 1914 by the avant-garde artists, which became part of the history of Russian performance. The heroes of that event, Kazimir Malevich and Aleksei Morgunov, dressed up in jackets with wooden spoons in the lapels and went out on Kuznetsky Most Street in the center of Moscow2. Their photos were published in the newspapers and were yet another reason for public discussion of the scandalous futurists.

Perhaps the St. Petersburg artists knew about the re-enactment of this walk organized by Avdei Ter-Oganyan in Moscow in summer 1992. An eyewitness to this event, art critic Andrey Kovalev, noted that it “did not cause any public reaction, from which we can conclude that the Malevich case not only lives, but also won.”3. The St. Petersburg artists would most likely agree with the opinion of the Moscow author. Although the photo with the participants of the action, marching with carrots, appeared in the press, it did not cause surprise.

In the booklet printed for the final stage of the project, Nadezhda Bukreeva and Alexey Kostroma described the concept of Malevich's Garden: “Any phenomenon becomes its opposite over time. [. . .] The rebellious artist quietly and imperceptibly turned into an honored academician. [. . .] The introversion of the Black Square, its inaccessibility to the uninitiated, [. . .] after consuming its harvest turns into a completely accessible and ordinary image.”4.

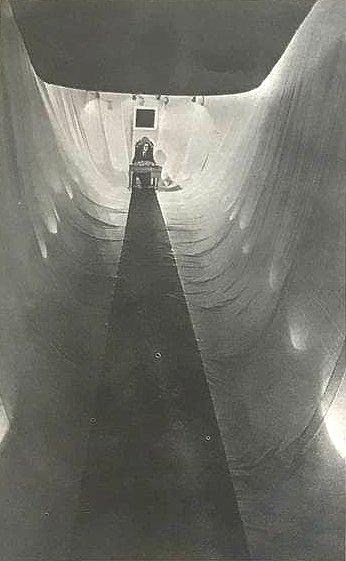

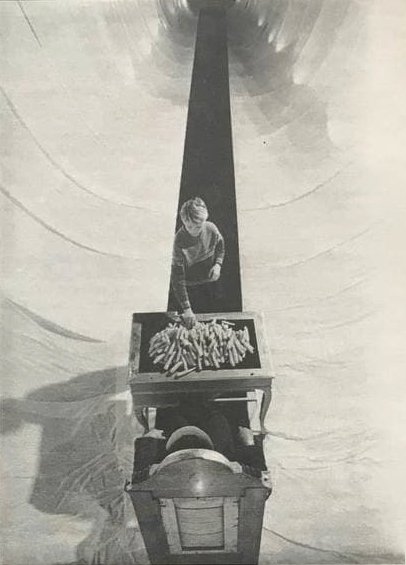

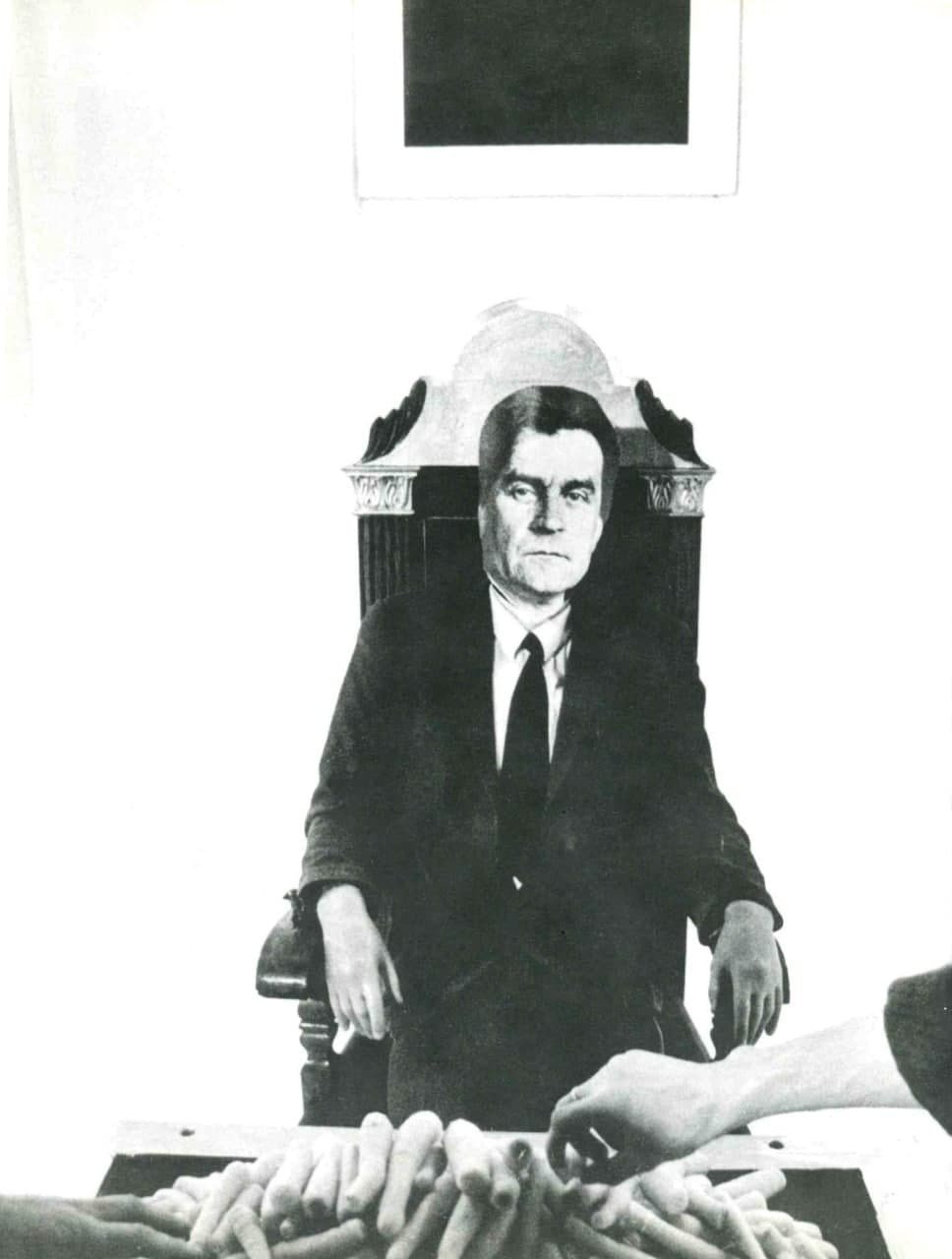

Visitors to the exhibition at the Ethnographic Museum could join in with eating the carrots. In the grand marble hall Alexei Kostroma and Vladimir Mikhailutsa built a pavilion of white canvas, at the entrance of which the papier-mâché carrots brought from Vasilievsky Island were installed. At the end of this structure was a table with the vegetables dug up from the courtyard of the Academy. An actor in a Malevich mask was sitting at the table. A camera was directed inside the pavilion and the images broadcast on a screen in the exhibition space, so that the route of each participant who went to get the fruits of Malevich's Garden could be traced. By the end of the event, the harvest was symbolically and physiologically assimilated by the visitors.

Decades later, the Academy of Arts has still not completely accepted contemporary art. Here, the ability to draw an ankle correctly is still valued more highly than project activity, but the history of the Russian avant-garde is now included in the education program. The action Malevich’s Garden has also become a classic. In 2008, a reduced replica of the installation was produced for the exhibition The Adventures of the Black Square and later became part of the collection of the Russian Museum.

1. Tut-i-Tam: 1991–1996 (St.Petersburg: Lenekspo, 1997) p. 43

2. A. D. Sarabianov, “Dereviannaia lozhka,” Entsiklopediia russkogo avangarda, URL: http://rusavangard.ru/online/history/derevyannaya-lozhka.

3. A. Kovalev, “Futuristy vykhodiat na Kuznetskii” [text for the performance], Garage Archive Collection (Art Projects Foundation archive), APF-Trehprudny-D637.

4. Ogorod Malevicha [booklet], 1992.