The Movement of a Tea Table Toward Sunset

You can listen to the podcast on SoundCloud, Apple Podcast or Yandex.Music.

One of the most important locations on the art map of 1990s St. Petersburg was Borey Gallery, which was in a semi-basement on Liteyny Prospekt, near Nevsky Prospekt. This independent space, managed by Tatyana Ponomarenko, organized exhibitions, operated as a publishing house, had a bookstore and café, and was a venue for a range of events, from friendly meetings to conferences. The writers Arkady Dragomoschenko, Alexander Skidan, Dmitry Golynko-Wolfson, and Boris Kudryakov, the philosophers Alexander Sekatsky and Valery Savchuk, the artist and researcher of Leningrad unofficial photography Valery Valran, and many others were frequent guests at Borey.

It was in this intense atmosphere that the artists who created the New Blockheads met. The group existed from 1996 to 2002. In a text about the group’s first summer, the artists described what brought them together: “Nobody knew what was happening in the Borey catacombs, where we were working on creating contrived stupidity. Are we really blockheads? Are we bluffing about being hopeless? No, it seems we really were in that stage of deep sterility, when any thought of work, of a bright accomplishment, turned us into an icy corpse. No accomplishments! Firstly, does anyone need our accomplishments? Secondly, we have already accomplished everything, as it was done before us. Thirdly, our incurable mediocrity does not allow us to accomplish something new, something perfect.”1.

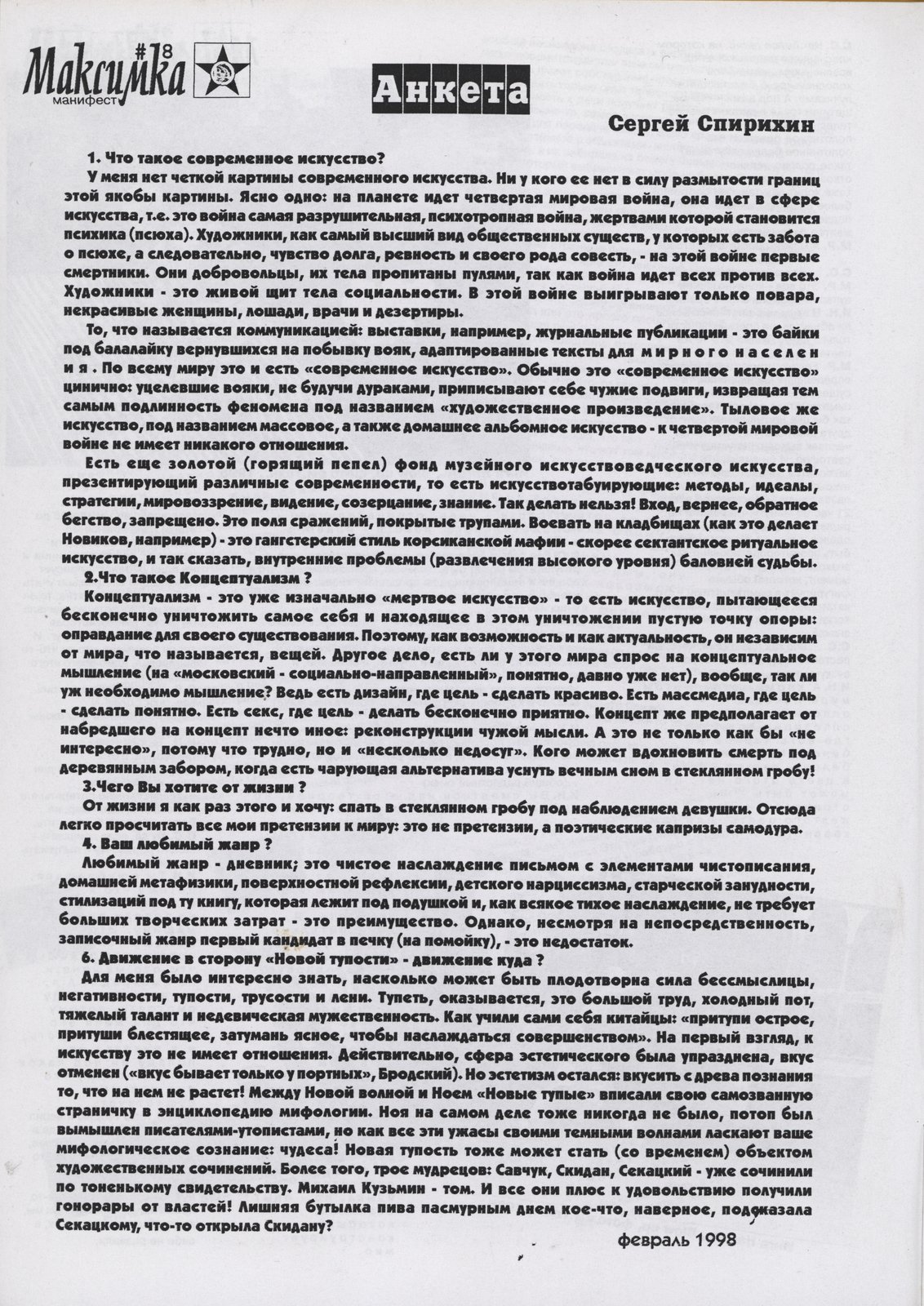

In spite of the apathy the artists attributed to themselves, the New Blockheads were fairly active. During the short period of the existence of the group, the core of which was Vadim Flyagin, Sergey Spirikhin, Vladimir Kozin, Igor Panin, Alexandr Lyashko, and Inga Nagel, it participated in exhibitions and festivals at various St. Petersburg venues and organized several dozen performances and events. The “stupidity” of the artists made it possible to see art in the most ordinary things and to act swiftly. This does not mean that participants were frivolous. As Sergey Spirikhin noticed, searching for stupidity is “serious work, cold sweat, great talent, and non-girlish masculinity.”2.

The artists used various methods to become “blockheads.” For example, they let themselves forget about simple everyday rules. During the performance Slavic Bazaar, Igor Panin poured borscht on the white starched tablecloth, as if he didn’t know that soup is usually served in dishes. In Red and Black, Vladimir Kozin smeared his face not with foam but with black shoe polish before shaving.

Another manifestation of “stupidity” is the inability to stop: to stop repeating your mistakes. One performance that demonstrated this inability was Vanka-Vstanka by Vadim Flyagin, in which the naked artist tried to “lie down and relax on five chairs that parted under him, and as a result he fell,” getting covered in abrasions and bruises3. The author continued his attempts within 1.5 hours, exhausting himself and the audience.

“Stupidity” can also mean a person confessing to unoriginality, copying. Group members happily made deliberately “profane” replicas of works or events created by other artists who were more successful or already included in the history of art. Timur Novikov, who was perhaps the most famous St. Petersburg artist of the 1990s, was the object of their close attention.

In 1998, the New Academy of Fine Arts, founded by Novikov, organized the action Burning Vanities to mark the 500th anniversary of the execution of Girolamo Savonarola, the Florentine preacher and fighter against excesses. This event marked the group’s turn to the “new seriousness.” Some of their old works, deemed too “frivolous” by the artists, were burnt, along with pornographic magazines and drugs. New Blockhead Sergey Spirikhin wanted to attend and make an omelet on the bonfire of other people's work, but he did not have time4.

As a result, he decided to stay closer to Borey Gallery. In the courtyards opposite the gallery he set fire to broken stretchers, cooked a simple dish, and ate it right there.

Present at Spirikhin’s action were photographer Alexander Lyashko, who documented it in several shots, and a couple of bystanders. Of course, New Academy academy artists didn’t hear anything about Omelet. Many of the events organized by the New Blockheads were invented by members of the group for themselves. As Vladimir Kozin recalls, “there was an idea of activity without result. The state into which we entered thanks to this activity was important.”5. One work by the group, which has become a legend in St. Petersburg art circles, is The Movement of a Tea Table Toward Sunset. Seven Days of the Journey, which was dedicated to the art of spending time.

The background is as follows: in August 1996, Larisa Skobkina invited the New Blockheads to take part in the second Festival of Experimental Arts and Performances, held in the Manege Central Exhibition Hall. The artists decided that the journey to the performance venue could be turned into an event. Alexander Lyashko, the author of the idea of this performance, described what happened: “I was working as a janitor at that time and took a set of white elephants and a round Riga table on one leg from the apartment where my grandmother died. I gave away the elephants, and the table stood for a long time in my room on Manezhny Lane. I thought, this is great, I can hike from Manezhny Lane to the Manege along with a table and folding chairs, stop along the way, sit down at the table and talk about art. So that’s what we did. Spirikhin recorded all our conversations on a typewriter."6.

The trip took the whole day. Some recall that the talks were accompanied by tea, others that stronger beverages were involved. The stops occurred at various points in the city center: on the Fontanka Embankment and Panteleimonovsky Bridge, leading to the Summer Garden, at the Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood, on Palace Square at the Alexander Column. The last point on the route was the porch of the Manege, where the New Blockheads performed for six more days, not only for themselves but also for the general public.

In most of the groups works everyday life becomes art with the help of a little shift in the order of things. For example, the city turns out to be as suitable for table conversations as the kitchen or the Borey café. As Igor Panin noted: “the point of the artist is to use the environment and include it in your idea. [. . .] It's like when dealing cards: you have a certain hand and you play with the suits you have. The same goes for the city. We started in 1996… and just managed to do something in places where it’s now impossible.”7. As interpreted by the New Blockheads, stupidity is ultimately the ability to see opportunities for freedom that give time and space to the artist.

1. A. Lyashko, I. Panin, V., Flyagin, and S. Spirikhin, “Diletantizm leta,” Maksimka, 2, 1998, p. 23..

2. Sergey Spirin, “Anketa,” Maksimka, 2, 1998, p. 8.

3. M. Raiskin, “Osobennosti natsionalnoi spontannosti,” Maksimka, 4, 1999, http://old.guelman.ru/maksimka/n4/anat.htm

4. Spirikhin, “Vozmozhno, Bekket” (Noviye Tupiye v izlozhenii S. Spirikhina),” Opushka, February 16, 2009, http://opushka.spb.ru/text/spirihin_bekket.shtml

5. U menia ne bylo nichego, no mne pochudilos’, chto ulitsy — moi,” Raznoglasiia, October 26, 2016, https://www.colta.ru/articles/raznoglasiya/12844-u-menya-ne-bylo-nichego-no-mne-pochudilos-chto-ulitsy-moi#4.

6. Alexander Lyashko: “Performans byl estestvennym sostoyaniem hudozhnika”. Colta.ru. June 15, 2016. URL: https://www.colta.ru/articles/art/11449-aleksandr-lyashko-performans-byl-estestvennym-sostoyaniem-hudozhnika.

7. “U menia ne bylo nichego, no mne pochudilos’, chto ulitsy — moi."