In connection with the Neue Slowenische Kunst retrospective in Moscow, Zdenka Badovinac will consider how Yugoslav art responded to the Russian avant-garde, one of NSK’s most important sources of inspiration.

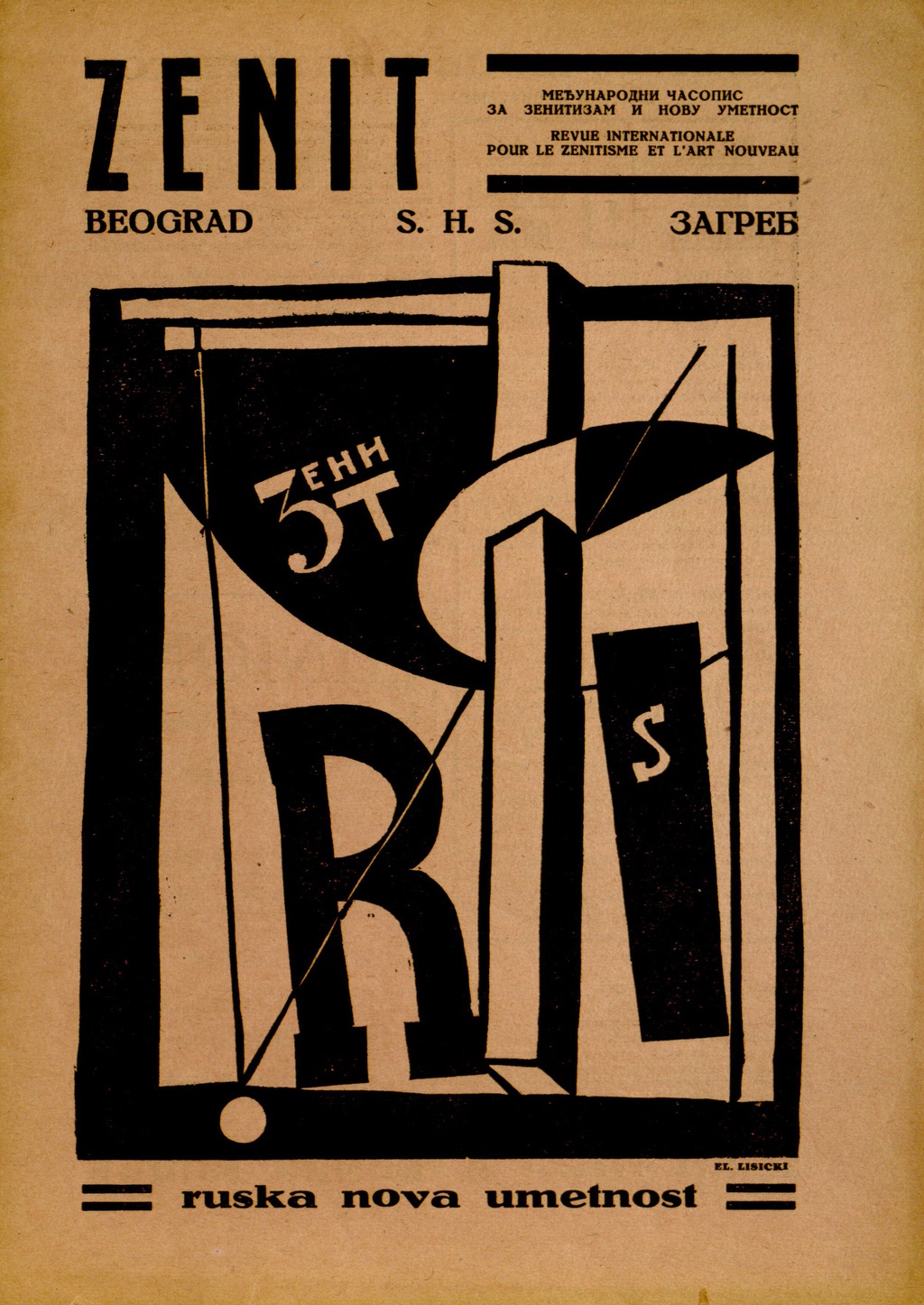

Given that the historical avant-gardes of Eastern Europe were largely excluded from the dominant art history in Yugoslavia, as well as, for a long time, from the references of Yugoslav artists, when we look at the reception of these movements in Yugoslavia, we have to speak more about the role of absence in that reception rather than presence.

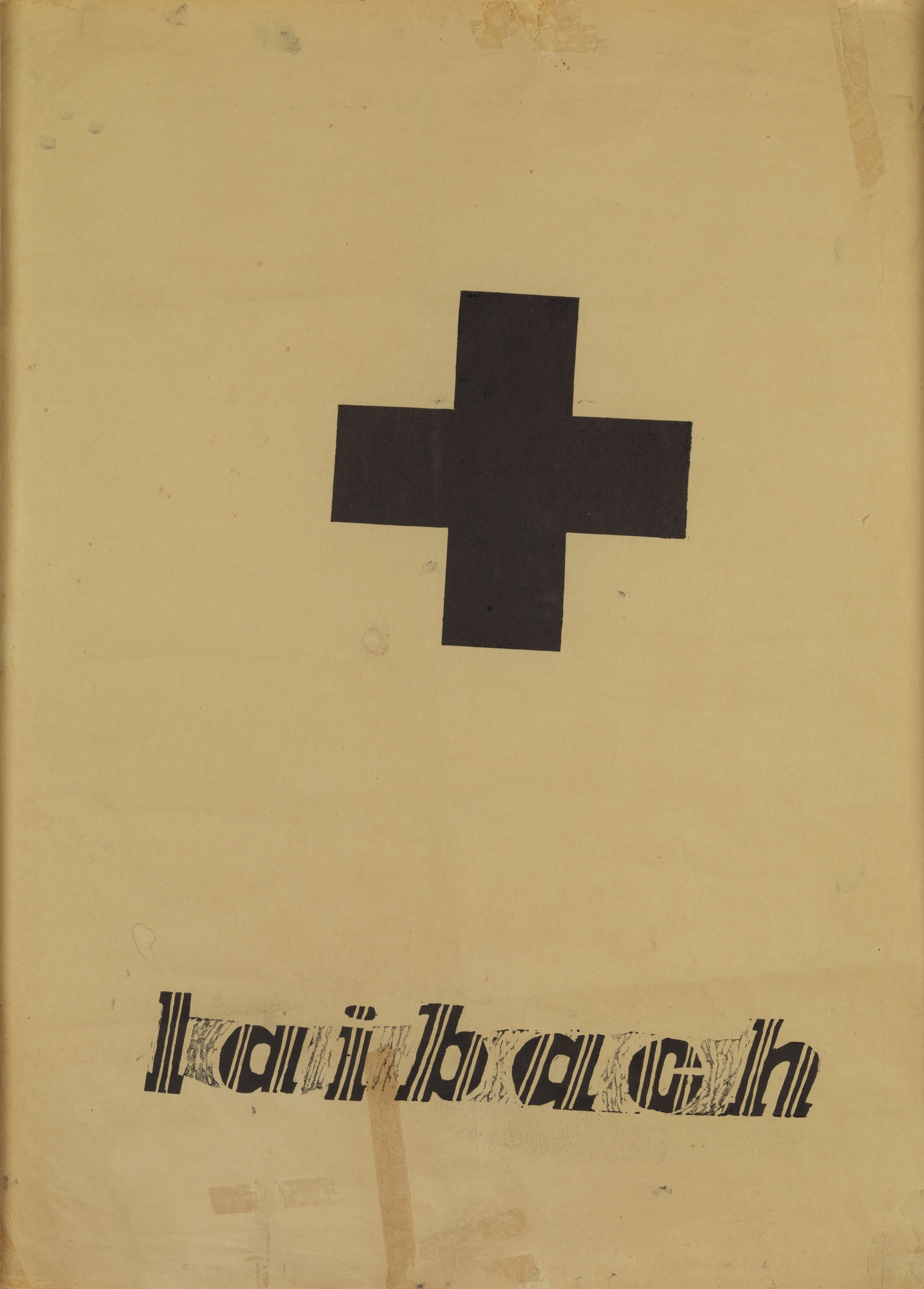

The post-war avant-garde movements, in fact, discovered their own pre-war traditions predominantly through Western interpretations. It is well known that in the West, throughout the twentieth century, Russian avant-garde art was understood primarily in terms of its formal aspects, while its connection to everyday life was in many interpretations lost or blurred. Less known, however, is how these movements were perceived in Eastern Europe. When it comes to Yugoslavia, we can say that Yugoslav artists encountered the historical avant-gardes of Eastern Europe relatively late—in a more nuanced way only in the late 1970s and early 1980s—but even so, we cannot say that the spirit of these avant-garde movements was not always alive here. On the contrary, when we speak about the art of Yugoslavia in the period of self-management socialism, we need to consider the specific socialist context, in which many utopian ideas were incorporated, even if in actual practice they appeared in a largely degraded form. Although Yugoslav post-war avant-garde artists never directly criticized the dysfunctional nature of the social utopia, they nevertheless, in both their ideas and practices, provided a kind of social corrective to the existing situation. Utopia was thus continually present, if only in its absence and in the effort to make it present in art. This effort was pursued most conscientiously in the art of the NSK collective. While NSK is undoubtedly the successor to a number of different European avant-gardes, the Russian avant-garde occupies a special place in their work. In particular, NSK was interested precisely in making present the experience of their Russian predecessors, which to a large degree happens by making present Malevich’s image of absence.

We can say of NSK, then, that it made present a double absence—the absence of the history of the historical avant-gardes and the absence of any consistent socialism in the social practice of Yugoslavia.