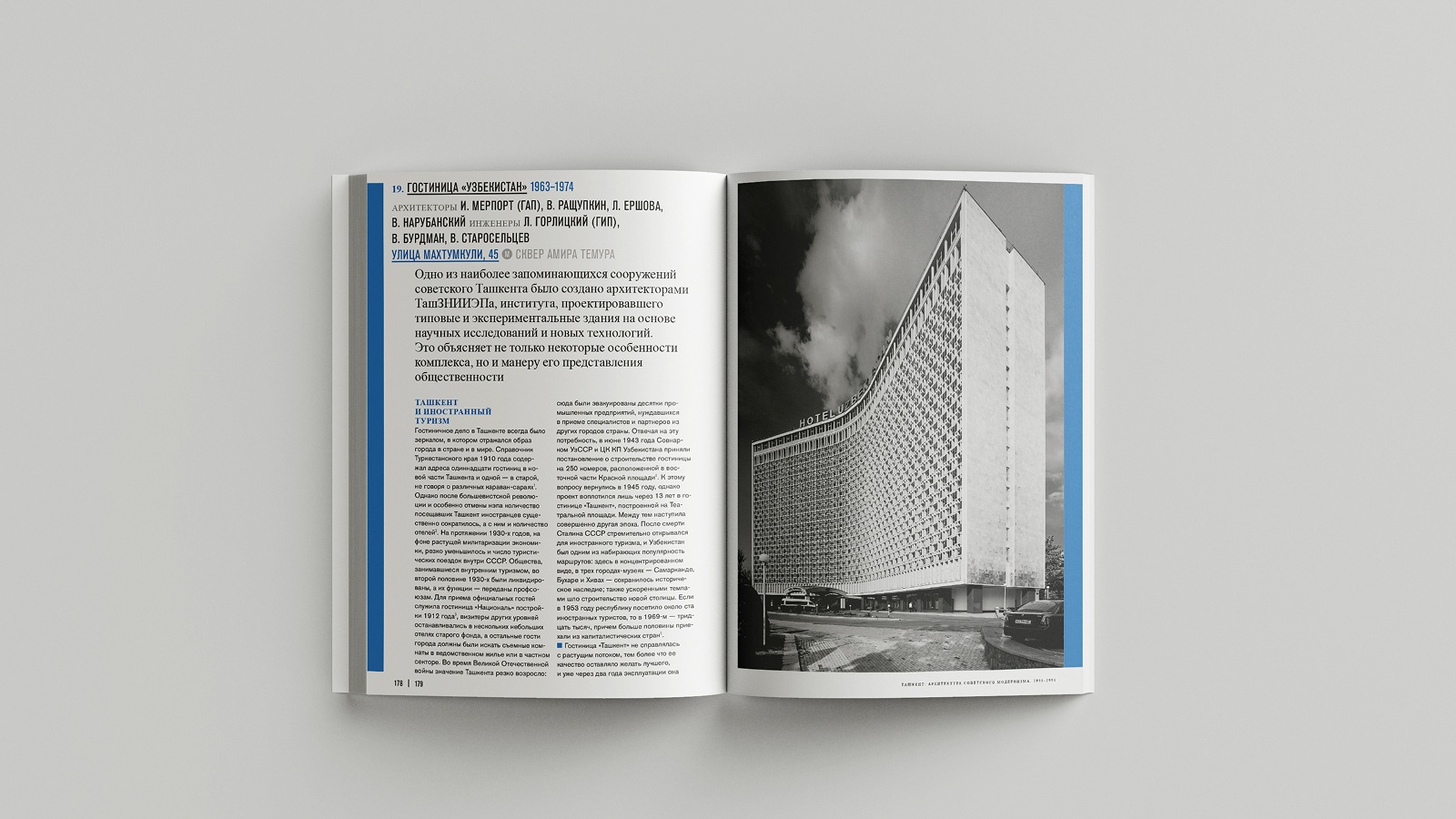

Tashkent, the fourth megalopolis in the USSR and the largest city in the Soviet Central Asia, was an inviting location for a variety of large modernist developments.

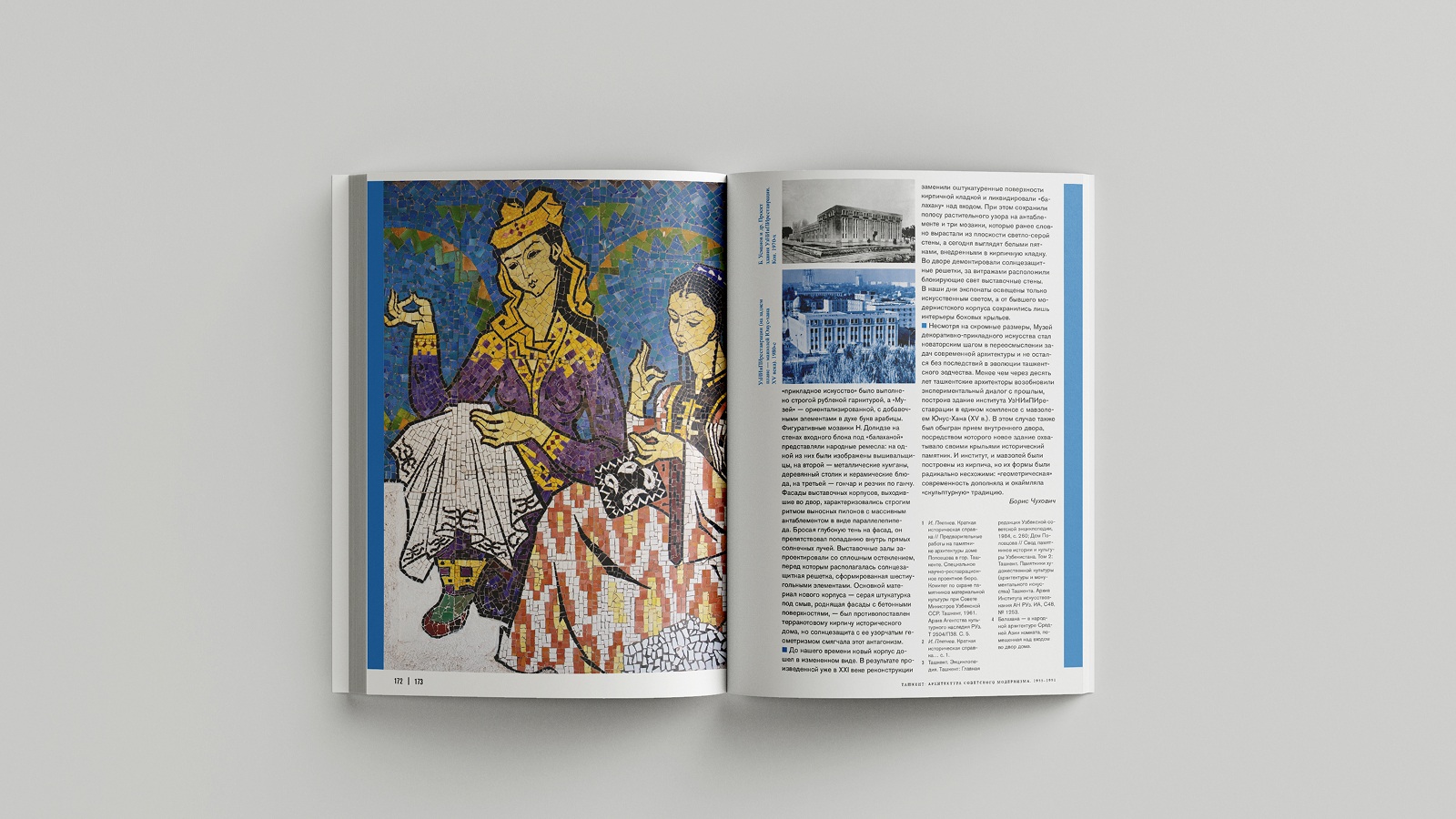

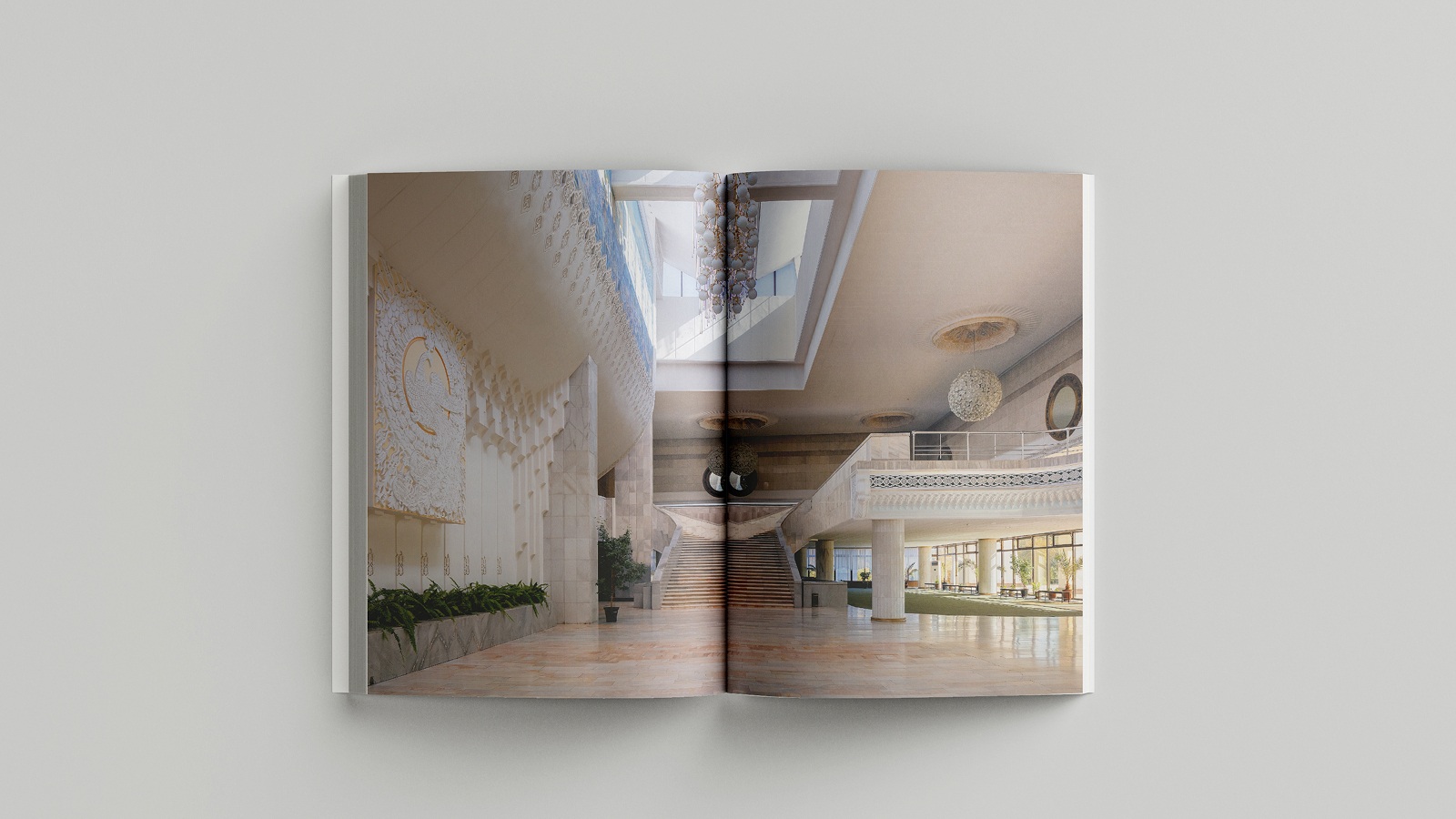

However, along with the size of the city, they were also a product of political will. The Soviet government, supported by local elites, envisioned the city as the “capital of the Soviet East,” a showcase for socialism to be presented to the countries of the Non-Aligned Movement. This meant that much more was expected of Tashkent’s architecture than of that of any other Soviet city. The capital of Uzbekistan had to maintain its southern or, as the late Soviet generations saw it, “eastern,” character, yet it was supposed to look dynamic and modern in comparison to the ancient capitals of Central Asia, such as Samarkand, Bukhara, Khiva, and Kokand.

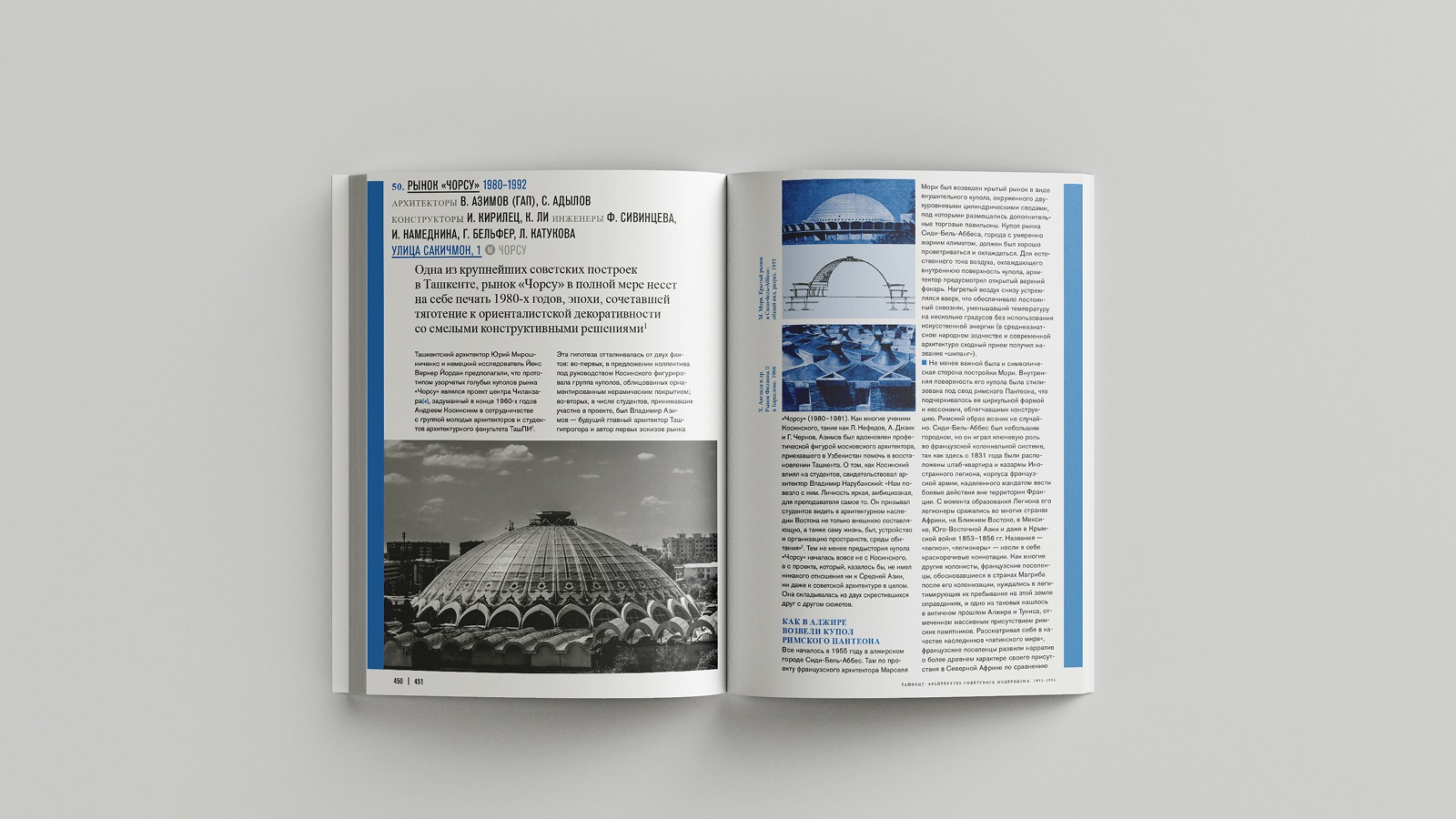

Guided by these imperatives, the urban planners of Tashkent decided to build a new modernist capital not near but in the center of a city that dated back thousands of years. This vision predetermined the urban planning and the typology and character of Tashkent’s key buildings of the 1960s to 1980s. Discussing fifty modernist buildings in the city, the authors trace the general evolution of Tashkent’s architecture, with its protagonists and the various (sometimes conflicting) cultural contexts that shaped these impressive buildings in one of the most unusual of the world’s modernist capitals.