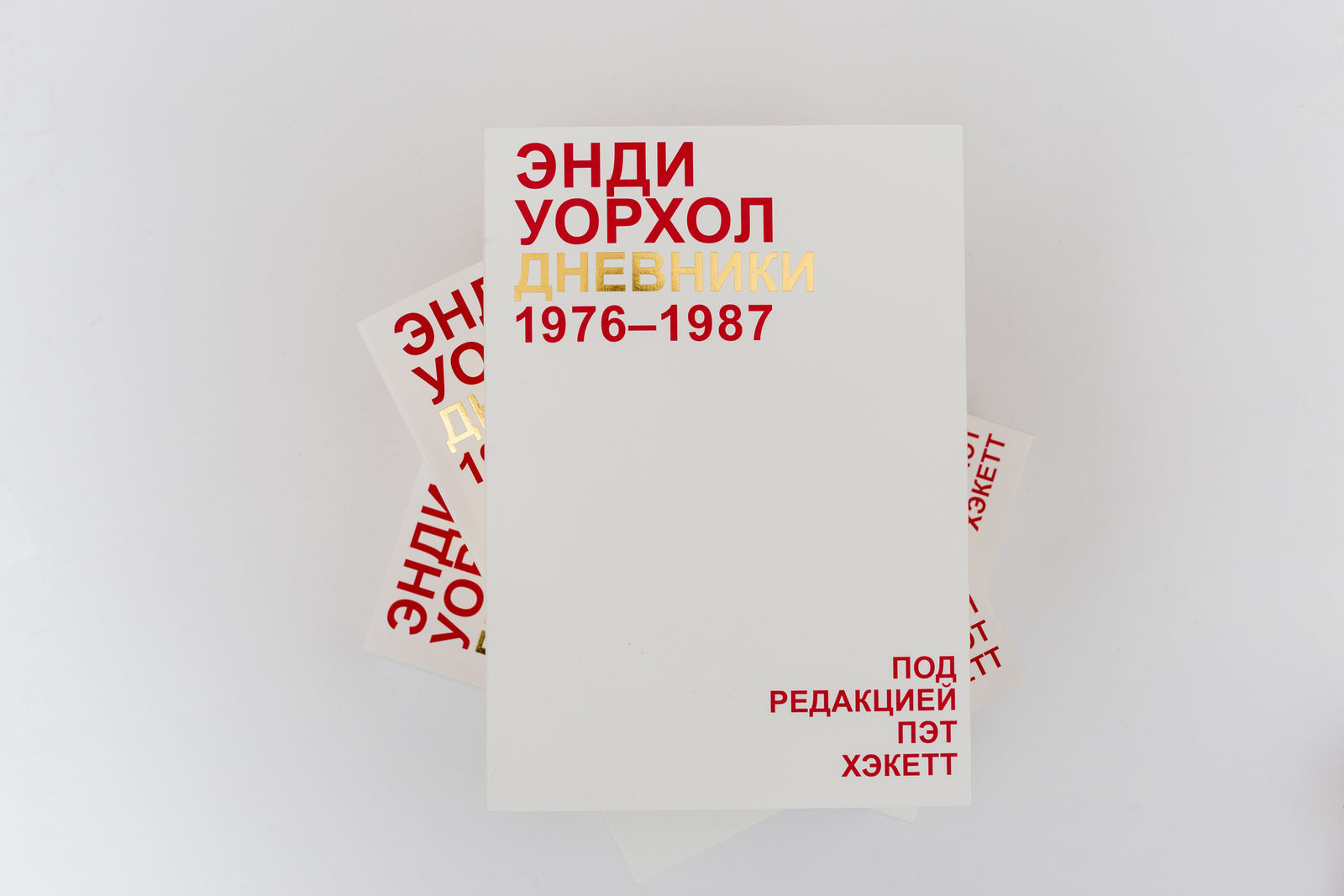

Andy Warhol’s (1928–1987) diaries were first published posthumously in 1989, edited by his friend and confidante, Pat Hackett, who transcribed Warhol’s diary entries for more than ten years.

Hackett chose the most interesting entries from over twenty-five thousand pages she had transcribed. The first entry dates back to November 1976, and the last one was made on February 17, 1987, just before Andy Warhol went into hospital for an operation on his gallbladder, and five days before his death.

To Warhol, the diary was an opportunity to scrutinize his own life, but also, as Hackett points out in the preface, to satisfy tax auditors, who ran annual inspections of his business from 1972 (Warhol believed the reason for that was the anti-Nixon poster he made during the campaign that year). In the introduction, Pat Hackett describes the routine of writing Warhol’s diary. Each business day he called her at 9am and talked about the previous day (Friday and the weekend, if it was Monday): his trips, his meetings, the parties he had been to, and—always in minute detail—his expenses, including 10 cent calls from phone booths. Hackett transcribed the story and then used a typewriter to make diary pages. Several times a month, she brought the typewritten pages to The Factory, where they were stored in special boxes.

In the preface, Hackett also speaks about Warhol’s daily routine, The Factory in the 1970s and 1980s, Warhol’s collaborators, Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, the making of his screenprints, what he liked in people, the things he was scared of, and about his personality in general.

For Warhol, there was nothing too insignificant to put it in the diaries, so Hackett edited them down, leaving what she found most interesting or most important in terms of understanding Warhol’s personality. However, the text retained Warhol’s intonation, his own voice, and his sometimes confusing and self-contradictory expressions. At times the reader has to struggle through the text, just like in a live conversation. This effort the reader has to make is “part of the unique experience of diary-reading – watching life unfold naturally, with its occasional confusions.”