The exhibition Kholin and Sapgir. Manuscripts, which is currently on show at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, explores the life and work of two key nonconformist Russian poets—Igor Kholin and Genrikh Sapgir. Garage Research have prepared an overview.

Overview of publications for the exhibition Kholin and Sapgir. Manuscripts

Overview by Ilmira Bolotyan, Maryana Karysheva, Valery Ledenev, Maria Shmatko and Yury Yurkin

Виктор Пивоваров. Холин и Сапгир ликующие.

[Viktor Pivovarov. Kholin and Sapgir Triumphant]

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2017

Viktor Pivovarov’s book was published in conjunction with the exhibition at Garage and includes reproductions from his earlier album of the same name, as well as excerpts from his own writings and texts by a number of his friends and colleagues (including Viktor Krivulin, Konstantin Kedrov, German Getsevich, and Pavel Pepperstein).

‘Sapgir’s poems on paper are but a score that needs to be vocalized,’ Konstantin Kedrov writes. Reading Kerdrov’s reminiscences of Sapgir ‘breathing’ the poem Sea in the Sink on a Paris stage, one realises the scope of what a written text cannot convey. Igor Kholin is remembered as a ‘great zen master, who knew that Buddha’s true essence reveals itself in a dung hill in the backyard.’ (Pavel Pepperstein)

According to one of the many anecdotes remembered in the book, Kholin and Sapgir were once paid for their performance with sacks full of Gzhel ceramics, instead of the forty rubles they were promised before going onstage. Passers-by were astonished by the sight of two strange men smashing ceramics, piece by piece, until they destroyed everything they were given.

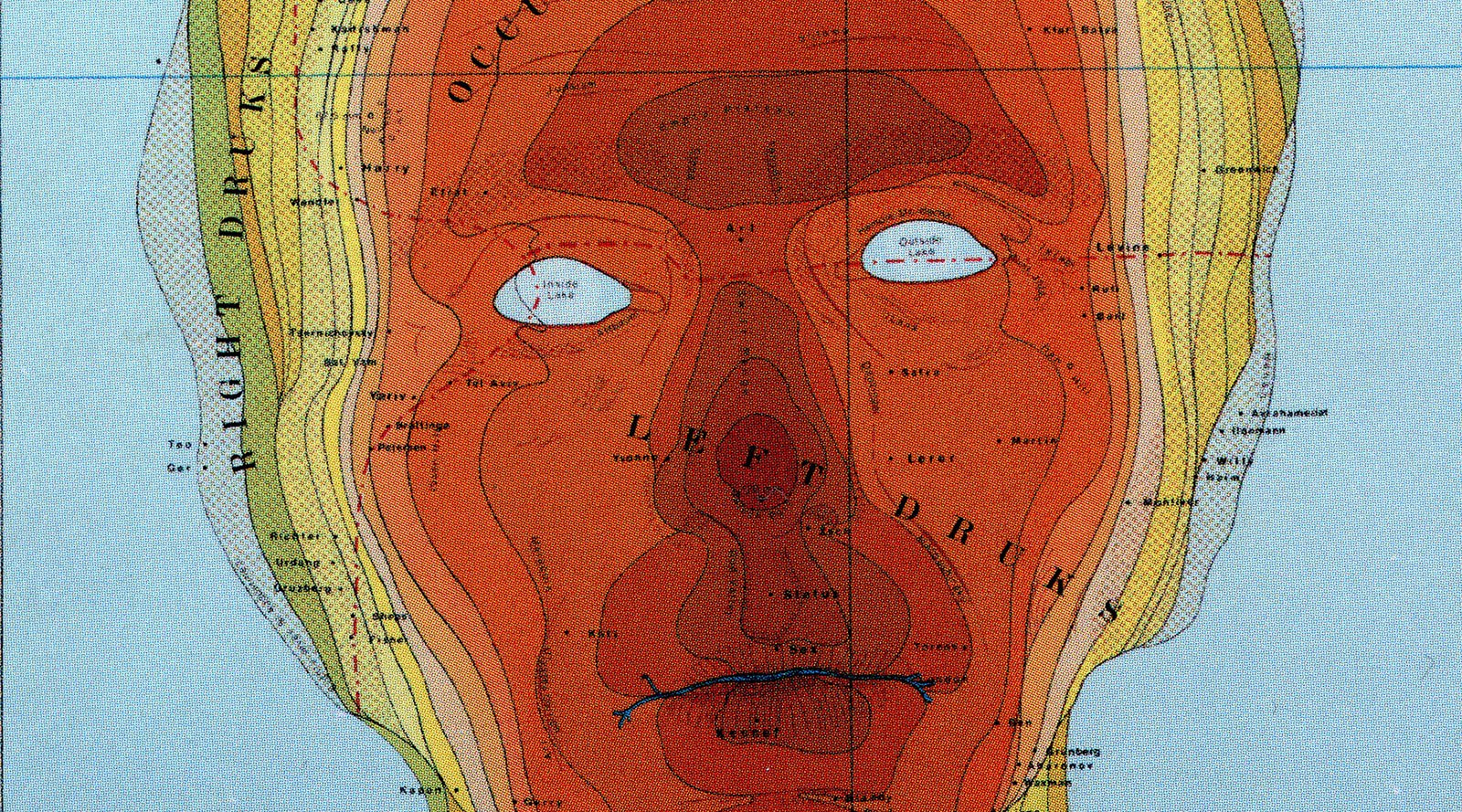

In his album, Viktor Pivovarov rewrites and mythologizes the lives of the two poets, drawing on photographic and textual documents to artistically rethink their biographies. Pivovarov’s Kholin and Sapgir stand, lie, drink, spit on the ground, and create havoc (the image must have been suggested by the Gzhel incident). They also have fun with their girlfriends, read books, and even travel to hell (with Dante himself as a guide), before eventually finding themselves in a garden.

The garden as a metaphor of heaven is a recurrent image in Pivovarov’s work. The heaven he has prepared for Kholin and Sapgir is full of houris—and that is, without any doubt, the best present their best friend could offer them. I. B.

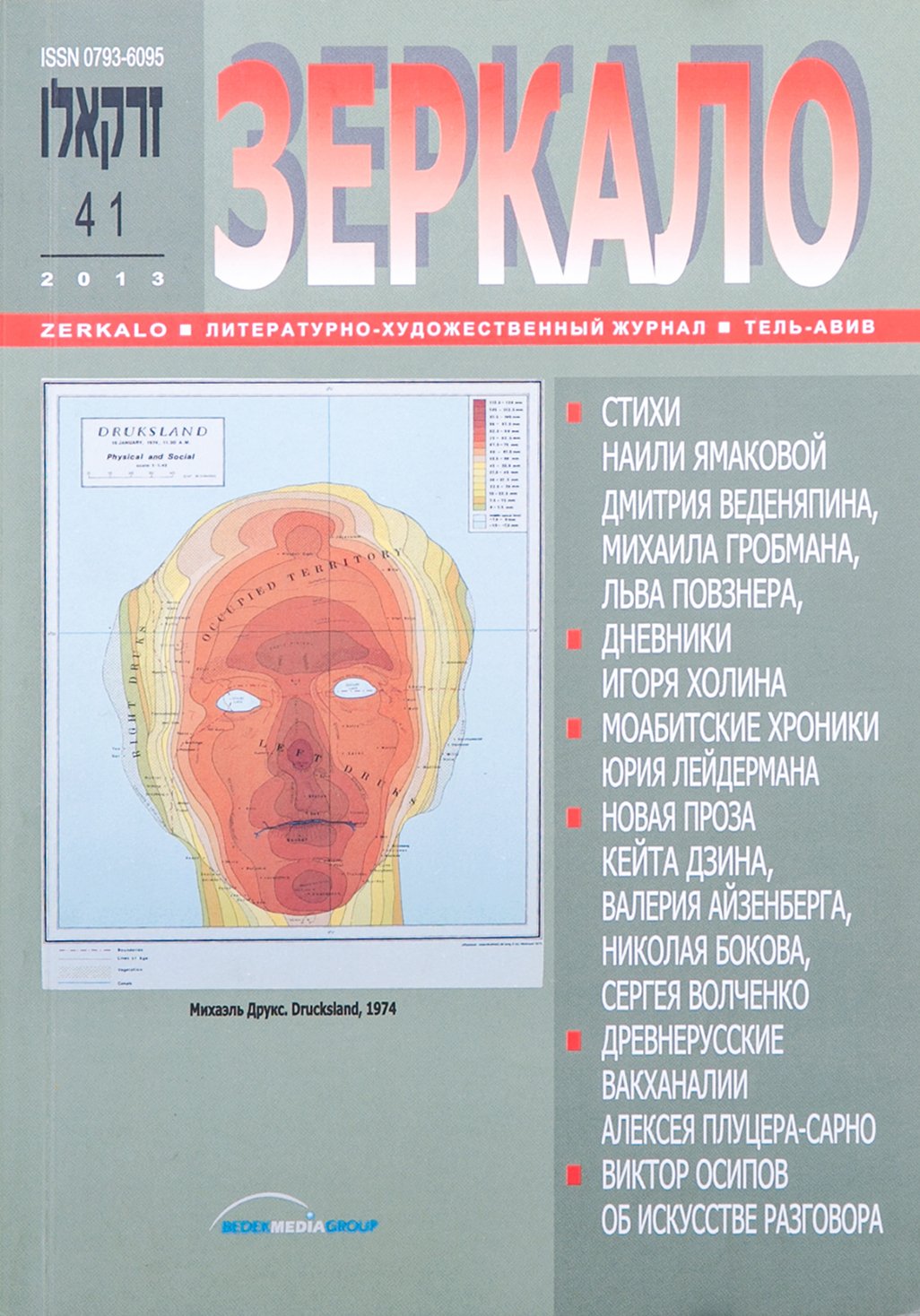

Игорь Холин. Дневники.

[Igor Kholin. Diaries]

Zerkalo Art and Literature Magazine, 41, 2013

‘He who seeks truth writes to his diary every day,’ Mikhail Grobman states in the introduction to Igor Kholin’s 1966 diaries published in the journal Zerkalo. Along with an account of his daily routines, travels and meetings, Kholin’s diaries contain ruthless portraits of people from his circle, brief reviews of books and artworks, and some aphorisms he wanted to remember (‘Whatever you say of a man will turn out to be true.’)

Some evenings and parties are described in more detail, and of several people Kholin has written more than on than others, one notable example being his teacher Evgeny Kropivnitsky. The diary is accompanied by Genrikh Sapgir’s poem The Morning of Igor Kholin and an index of names.

A later diary of Igor Kholin, which was written in the early 1990s, is featured in the exhibition Kholin and Sapgir. Manuscripts. M. K.

Великий Генрих. Сапгир и о Сапгире.

[The Great Genrikh. Sapgir on Sapgir]

Russian State University for the Humanities, 2003

This collection was published in the year of Genrikh Sapgir’s seventy-fifth anniversary and includes his own writings (some previously unpublished, like the poem Perhaps! or Italian Notes written in prose) as well as a selection of texts about him—academic analyses, essays and reminiscences by his friends and contemporaries.

In his article “Introduction to the Poetics of Genrikh Sapgir: The System of Opposites and the Strategy of Overcoming Them”, academic Yury Orlitsky describes the poet’s legacy as ‘the golden mean between radical modernism <…> and postmodernist tendencies that have prevailed in Russian art over the past few years.’ ‘Sapgir somehow brings the polar opposites together,’ he continues. ‘On the one hand, he often appeals to the national tradition (<…> as represented, for example, by Pushkin and Fet), but on the other, he interprets it as a kind of proto avant-garde.’

Orlitsky’s argument regarding the visual and performative nature of Sapgir’s writings is of particular interest in the context of contemporary art. The exhibition at Garage offers ample evidence of the spatial arrangement of typewritten texts creating ‘aesthetic images’ of poems. Visitors can also hear recordings of Sapgir reading his own poems, which as Orlitsky claims, were written to be read out loud—pronounced.

Vsevolod Nekrasov discusses the figure of Sapgir in the context of the Soviet culture of the first post-Stalin years, while the memoirs of Valentina Kropivnitskaya and Militrisa Davydova are devoted to the Lianozovo School, to which the poet belonged. V. L.

Максим Д. Шраер, Давид Шраер-Петров. Генрих Сапгир — классик авангарда.

[Maxim D. Shrayer, David Shrayer-Petrov. Genrikh Sapgir: An Avant-Garde Classic]

Dmitry Bulanin Publishing, 2004.

Published in St. Petersburg, Maxim D. Shrayer and David Shrayer-Petrov’s Avant-Garde Classic is the first book about the life and work of poet, writer and translator Genrikh Sapgir. The study offers a number of arguments to support the oxymoron in the book’s title, some more convincing than other. As Olga Filatova points out, ‘It is interesting that a poet who, according to all formal criteria, is closer to the avant-garde than to classical art, is so attentive to genre markers.’ ‘Genrikh was not an avant-garde poet in a traditional sense,’ Viktor Krivulin agrees. Sapgir himself also touches on the subject when he writes about Schnittke. ‘What I find important in Schnittke <…> is the way he combines tradition with the avant-garde. I have always felt the need to do so.’

Analyzing the development of nonconformist literature, the authors trace its roots back to Russian folklore and the futurist writings. Sapgir, they argue, inherited the ‘art as a means to an end’ approach from his teachers and predecessors, however, in his work it evolved into ‘art as a fracture.’ As early as in the 1970s, he set himself in opposition to the future Moscow Conceptualists, claiming that they had a different approach to similar subjects. ‘You are explorers, <…> as for me, I do not care whether the technique I use was discovered a million years ago or just the other day. I’ll use it if it helps me express myself.’

As Viktor Krivulin remembers, Sapgir ‘did not just read in his performances, but drew his poems from within, turned himself inside out to reveal them… The energy wave he created when he read was similar to the one that the young Brodsky produced in the autumn of 1960.’ Another thing the two poets have in common is their mastery of the word—‘the sound construct’ that withstood, in Sapgir’s work, all sorts of trials and tribulations brought onto it by the poet’s sincerity and taste for the absurd (see chapters The Singer of Psalms and The Disintegration of Verses).

David Shrayer-Petrov’s essay “The Excitement of Dreams”, which takes up the third of the book, is based on Sapgir’s diary entries and correspondence and is nothing short of a memoir. Along with an analysis of Sapgir’s own life and writings, the book explores the developments in his circle and, more generally, isn the cultural context of the 1980s and 90s, touching on phenomena like the Lianozovo School or the late ‘patriarch’ period. M. Sh.

Nonkonformisten, Die zweite russische Avantgarde 1955-1988

[Nonconformist Artists. The Second Russian Avant-Garde. 1955–1988]

Sammlung Bar-Gera. Wienand, 1996

Igor Kholin and Genrikh Sapgir belonged to the Lianozovo School that formed around the poet and artist Evgeny Kropivnitsky, who ran the literary studio Sapgir attended in the 1940s. Along with literary, the school has left an important artistic legacy, and the catalogue of the 1996 exhibition of works from Bar-Gera Collection at the Russian State Museum and the Tretyakov Gallery offers an introduction to the latter.

The unique collection of works by the artists of the so-called ‘second avant-garde’ (including Valentina Kropivnitskaya, Evgeny Kropivnitsky, Vladimir Nemukhin, Lydia Masterkova and Oskar Rabin) was successfully sold at an auction in 2016.

The book has two sections. The first one contains interviews with collectors and articles by Karl Eimermacher, Evgeny Barabanov and other scholars. The second section is an illustrated catalogue of the exhibition with artists’ biographies. Yu. Yu.