Garage's current exhibition, Louise Bourgeois. Structures of Existence: The Cells, features around 80 of the artist’s works. Garage Research has compiled a selection of general and specialized publications on the artist and her Cells series, now available at Garage Library.

Overview of publications on Louise Bourgeois

Overview by Evgenia Abramova, Elena Ishenko, and Valeriy Ledenev

Mignon Nixon. Fantastic Reality. Louise Bourgeois and a Story of Modern Art.

Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005

The 2005 book by American professor, art historian, and author of journal October Mignon Nixon is the first and most comprehensive critical study of Louise Bourgeois' work. Nixon’s analysis unfolds in a coordinate system where one axis represents psychoanalysis and the other feminism. From the first chapter the first chapter, dedicated to Bourgeois’ “discipleship” of Surrealism, Nixon’s narrative starts to resemble a web spun around the artist’s works, and in a way mimicking them. Louise Bourgeois, who remains at the center of this web, is envisaged as the one who creates the very history of modern art. The recurrent themes in her work of motherhood, violence, and death exist in a complex fantastical world, which Nixon arranges into the clearest and most meaningful structure possible, drawing on the history of psychoanalysis from Freud to Melanie Klein, and from Surrealism to feminist art. E. A.

Robert Storr, Paulo Herkenhoff, Allan Schwartzman. Louise Bourgeois.

London: Phaidon Press, 2003

This edition, offering a concise but thorough overview of Bourgeois’ work, is part of the Contemporary Artists series published by Phaidon Press and available at Garage Library in its entirety. Central in this publication is an essay by American curator and art critic Robert Storr. Despite being a seemingly traditional essay on "the life and work of …," it offers a more profound analysis of the artist's practice than can be found in most publications, which abound in straightforward comparisons and psychoanalytical clichés. Storr’s analysis is descriptive and formalist on the one hand (one of the central objects of his study is the Bourgeois’ use of new artistic media and unconventional materials and the transformation of sculpture into environments) and political on the other. Storr of course focuses on a biographical narrative, but treats it not in psychological but rather in socio-critical terms, and thus approaches a feminist perspective in the artist's oeuvre. Apart from personal and psychological factors that informed Bourgeois' work, he analyzes the historical context, of which she was always very aware. Finally, he focuses on the artist’s critique of Modernist art, inevitably approaching a Postmodernist perspective. In a different essay featured in the book, Allan Schwartzman offers an analysis of one work: Cell (You Better Grow Up). The book also contains a selection of Bourgeois’ own writings. V.L.

Louise Bourgeois. The Return of the Repressed.

London: Violette Editions, 2012. 2 volumes.

The two-volume The Return of the Repressed, as its name suggests, is dedicated to psychoanalysis as a driving force and as an analytical tool that Louise Bourgeois repeatedly used over the course of her life. Compiled by her literary archivist Philip Larratt-Smith, the book features eight scholarly essays (volume 1) and around 80 texts by Bourgeois herself (volume 2). In his introduction to the book, Larratt-Smith explains the artist’s interest in psychoanalysis in a truly Freudian way—by the death of her father. Similarly, her disposition for art is connected to the death of her mother. Other contributors to the publication (Mignon Nixon and Donald Kuspit, among others) delve deeper into psychoanalysis, expanding on the encounter with the Other ("I want to create bridges/ what I want is to be close to the others"); unconscious jealousy ("Suddenly I perceived my jalousy [sic] and hate of Sadie (her father’s lover — E. I.) […] this jalousy [sic] was utterly repressed"); the father figure (Bourgeois recalls her father meandering around the house in nightwear holding his genitals); the fear of being left alone; and the weight of memories. What this volume offers is essentially the artist’s biography told through phone calls, encounters, sudden depressions, and family stories. Her works are discussed in the context of her life and often appear to serve no other purpose than to illustrate Bourgeois’ biography and psychoanalytic theory. The straightforwardness of this approach is balanced by the artist’s own writings in the second volume: her correspondence, diaries, and little notes, where psychoanalysis is mixed with irony and poetry. Take her letter to a friend, written on an invitation to her solo exhibition at the Norlyst Gallery in New York in 1947: "If I make one two, three, / four statues in one / series it is because I / must repeat myself, to be / sure that my message/ reaches you, if you want / ten of them I will make ten, a hundred/ an infinity I will never / tire."

Олеся Туркина. Луиз Буржуа: ящик Пандоры / Olesya Turkina. Louise Bourgeois: Pandora’s Box.

Moscow: Ad Marginem Press, 2015 (in Russian and English)

New books on Louise Bourgeois appear across the world with admirable regularity, but hardly any of them are available in a Russian translation. One exception to this rule is Olesya Turkina's work published in 2001, when the first exhibition of Louise Bourgeois opened in a Russia at The State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. A new edition of this book was published by Garage in collaboration with Ad Marginem Press for the opening of the exhibition at Garage. Like many authors writing on Bourgeois, Turkina romanticizes her figure, drawing on the autobiographical nature of her works (an aspect of her art insistently underscored by the artist herself). Like Robert Storr, Turkina is interested in Bourgeois' critique of the Modernist project, and discusses her work in the context of the Russian avant-garde, which the artist was familiar with, having twice visited the Soviet Union in the 1930s. Turkina looks into the artist's affective turn and how instead of searching for a meta language, Bourgeois became increasingly interested in the physiological dimension of her own emotions and identity issues. Suggesting a possible gender approach to the analysis of Bourgeois' work, Turkina touches on the issues of the male and the female in a patriarchal society and on the androgyny of a great number of the artist's works. Stopping short of a theoretical analysis, Turkina offers insight into these aspects of Bourgeois' art through the artist's own words, to which she turns many times throughout the book. The publication ends with an almost literary account of an encounter with the artist, containing many curious details and descriptions. V. L.

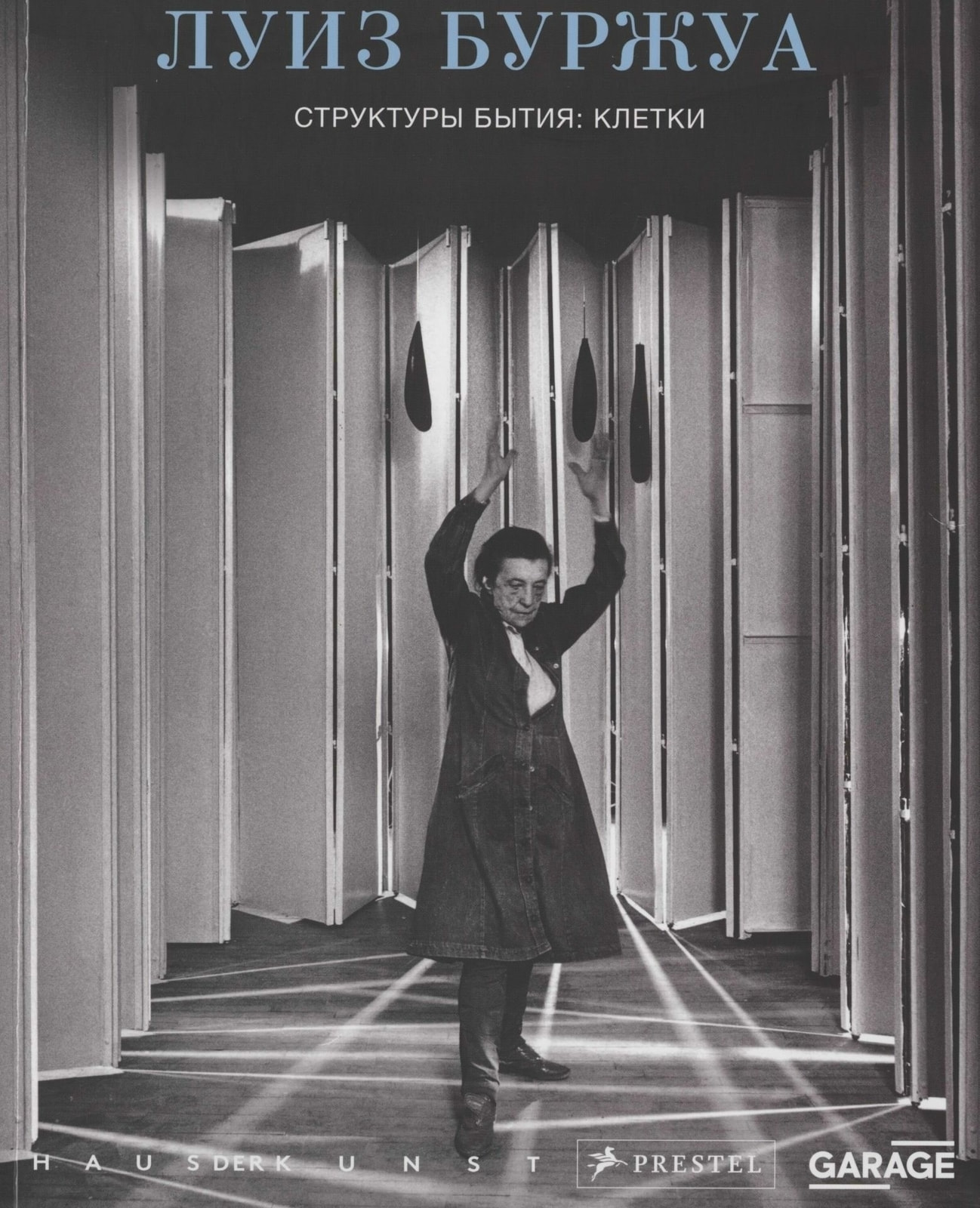

Louise Bourgeois. Struktury bytia: kletki (Louise Bourgeois. Structures of Existence: The Cells)

Munich, London, New York: Prestel; Moscow: Artguide Editions, 2015

The exhibition in Moscow of Louise Bourgeois. Structures of Existence: The Cells has travelled to Garage from the Haus der Kunst, Munich. The exhibition's catalogue, which has been translated into Russian Garage, offers a detailed overview and analysis of the Cells—a series of sculptures produced by the artist in the last 20 years of her life. Apart from an introductory text by the Haus der Kunst curator Julienne Lorz and two interviews with Bourgeois' assistant Jerry Gorovoy (talking to him are curator Lynne Cooke and Garage Chief Curator Kate Fowle), the book features five texts on some of the key works in the series: Precious Liquids (1992), Red Room (Child) and Red Room (Parents) (1994), Passage Dangereux (1997), Peaux de lapins, chiffons ferrailles à vendre (2006), and Cell (The Last Climb) (2008). Together, they create a very clear image of Bourgeois’ approach to art and the subjects that occupied her mind: being a woman, the physicality of experience, voyeurism, space and memory, body and architecture, the conscious and the unconscious. E. I.

Louise Bourgeois v Ermitazhe (Louise Bourgeois at the Hermitage).

Saint-Petersburg: State Hermitage, 2001

The Russian premiere of Louise Bourgeois’ works took place at the State Hermitage Museum in 2001. The catalogue for this exhibition is available in Garage Library. The publication contains little theory, which is limited to Sofya Kudryavtseva’s general account of Louise Bourgeois’ art, but it does introduce the reader to some of the lesser-known of Bourgeois’ works—her documentary photographs taken on her trip to the Soviet Union in 1934. The artist was going to describe her travels in an article, which unfortunately never saw the light of day. Her photographs, however, captured a street parade with banners in the aesthetic of the Soviet avant-garde and offer insight into what became of the genre in the 1930s, as well as a certain perspective on her own work (Bourgeois often mentioned her interest in Vladimir Tatlin). V. L.