From November 6 to December 10, Garage is hosting Open Systems. Stories of Self-Organized Art Initiatives in Russia: 2000–2015. To complement the exhibition and series of discussions with those who were behind such initiatives, Garage Research has compiled a selection of Russian and international publications on the theory and practice of self-organization in art, now available at Garage Library.

Review of Publications on Artistic Self-Organization

Overview by Evgenia Abramova, Elena Ishenko, and Valeriy Ledenev

Gabriele Detterer and Maurizio Nannucci (eds.), Artist-Run Spaces. Nonprofit Collective Organizations in the 1960s and 1970s

Zurich: JRP|Ringier, 2012, 294pp.

This anthology, edited by Swiss journalist Gabriele Detterer and Italian artist Maurizio Nannucci, was published by the influential Zurich JRP|Ringier in its Documents series, which often goes far beyond mainstream titles (although it does publish the ever-present Hans Ulrich Obrist too). Most of the book is devoted to the stories of seminal self-organized initiatives like Art Metropole (Canada), Printed Matter (USA), and Zona (Italy). Eastern Europe is represented by Gyorgy Galantai’s Artpool (Galantai’s works were featured at the recent Grammar of Freedom/Five Lessons exhibition at Garage).

In her introductory article, Detterer analyzes the general context in which self-organized initiatives emerged during the postwar decades, pinpointing their origins in the crisis of the 1970s and the “growing pains” of the expanding institutional system, which was becoming increasingly unable to represent the community and thus pushed the artists to look for an alternative. Although Detterer’s analysis is far from academic, she does make an attempt to define artist-run spaces (which still have no Russian equivalent), and discusses some of the associated phenomena, like artists’ zines or self-organized archives (many of which were later institutionalized). Today’s reader might be surprised to find that the big names featured in museum shows and major publications — like Sol LeWitt, John Armleder, Carl Andre and Lucy Lippard — started out with pioneering alternative initiatives, which emerged at the margins of the art world. V.L.

Self-Organized

London: Hordaland Art Centre, 2013, 163pp.

Artists, curators and art critics look into various aspects of self-organized initiatives in the current political and economical context of the Post-Fordist society, with cultural production and contemporary art at its center. Italian artist Céline Condorelli examines the notions of friendship and solidarity as key to any self-organization that rejects institutional hierarchy. Croatian curators from What, How and for Whom (WHW) point out its anti-nationalist potential, resistant to any such rampant or populist rhetoric. The final interview with Van Abbemuseum head Charles Esche with Ekaterina Degot and David Riff is devoted to the possibility of self-organization in a state institution. The most radical in this collection of texts is an essay by critic and curator Barnaby Drabble. Stating that many self-organized initiatives have turned into quasi-institutions with their own hierarchy and bureaucracy and have been acquired by big museums, centers or galleries, he insists on a return to their original potential to disrupt and to free artists from management and control. E.I.

Will Bradley, Mika Hannula, Cristina Ricupero, and Superflex (eds.), Self-Organization / Counter-Economic Strategies

New York: Sternberg Press, 2006, 336pp.

This compilation of texts was made by the group Superflex for the Nordic Institute for Contemporary Art (NIFCA), and was published by Sternberg Press in 2006. A reference book, it contains brief descriptions of self-organized grassroots initiatives and several essays discussing possible economic alternatives to capitalist strategies.

The central question posed in this volume is what these self-organized political, social, art, and activist groups can offer apart from a critique of the dominant capitalist discourse and mode of production. The answer is, their practices. The groups discussed come from across the world, from London to the countryside near Tilonia in India. Among them are LETSystem — a nonprofit coop with its own exchange system, currency and trading network in the US; The Catherine Ferguson Academy — a school for young mothers or girls expecting a baby located in a farm near Detroit; KPFK and Pacifica — an independent LA educative radio funded by listeners; and Open StreetMap — constructed by users from across the world and allowing unlimited access to data, which commercial maps do not.

The projects discussed include Guerilla Girls, fighting for female artists’ rights for self-expression, and The Coconut Revolution, a documentary about the struggle of Bougainville Island indigenous people in Papua New Guinea against Rio Tinto Zinc’s mining plans in 1988–97. Critical essays are complemented by the initiative’s manifestos, which revisit key capitalist notions such as “creative destruction,” which they eloquently rename “destructive reproduction,” and “gross national product,” which they call “gross criminal product.” E. A.

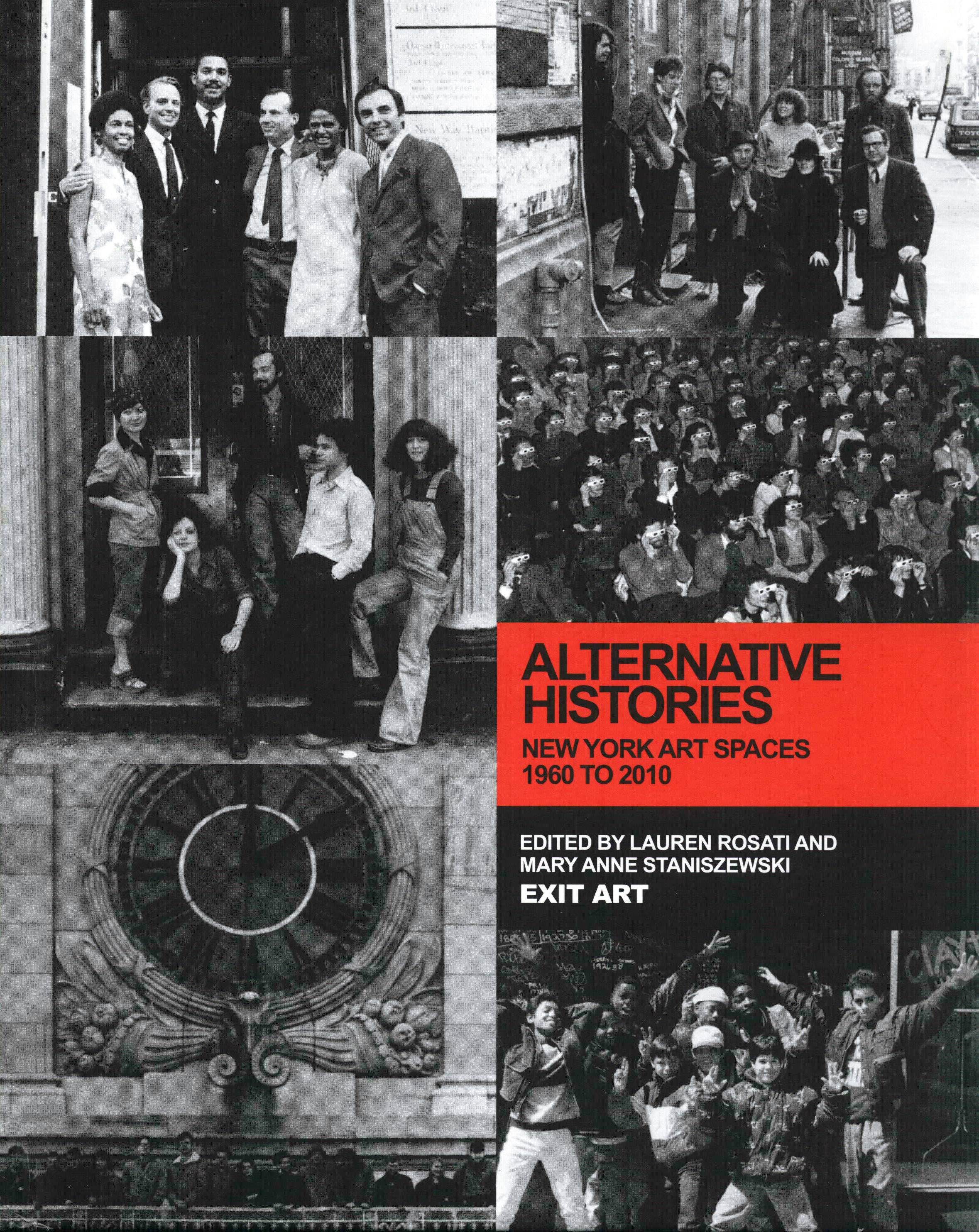

Lauren Rosati and Mary Anne Staniszewski (eds.), Alternative Histories. New York Art Spaces, 1960 to 2010

Cambridge: MIT Press, 2012, 404pp.

Like the previous one, this collection of texts is a kind of a reference book containing information on 140 alternative initiatives that have emerged, vanished or evolved into institutions in New York over half a century. But unlike Self-Organization / Counter-Economic Strategies, with its patchwork structure, Alternative Histories puts the stories of spaces and people behind them in a political, economic, and social context to show what kind of order they resisted, and what they associated themselves with. An important element in these stories is the city and its spatial organization, which can equally help or destroy an initiative.

The stories of these spaces are stories of breaking free. In the 1960s, alternative spaces emerged in opposition to “values and priorities imposed by all institutions.” Soho, where the first exhibition in support of the Student Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam took place, became the heart of this movement. But by the 1980s Soho had become gentrified and unaffordable for artists, who moved on to areas like the South Bronx.

And if in the 1970s alternative spaces did not have any kind of organization or management structure and did not receive any funding (were non-commercial), in the 1980s some of them had six- or seven-digit budgets, legal status, and were run by curators or managers instead of artists.

How could they still be alternative? To the editors, the answer is as follows: "Organizing as collectives, collaboratives, and laboratories, and using communication networks, these artists, scientists, architects, designers, writers, composers, and engineers integrate technology with craft, and theory with practice, to serve new social, political, environmental, and aesthetic priorities. As these communities create new models of possibilities for our future ... let us hope they succeed." E.A.

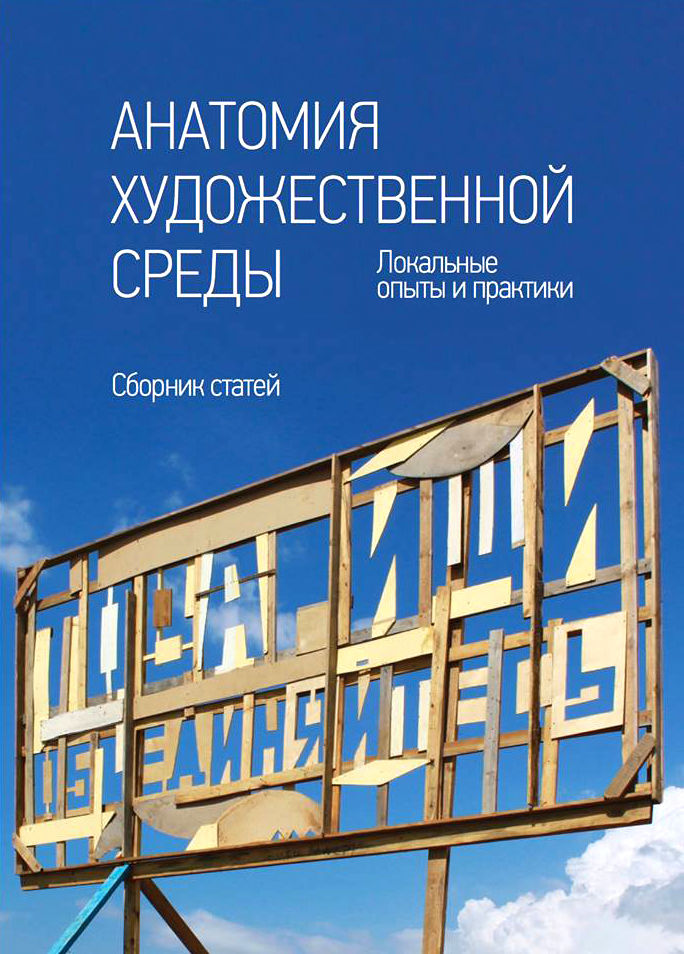

Konstantin Zatsepin (ed.), Anatomiya khudozhestvennoy sredy: lokal'niye opyty i praktiki. Sbornik statey (Anatomy of the Art Milieu: Local Cases and Practices. A Collection of Articles)

Samara: Publisher?, 2015, 85pp.

This collection of articles compiled by Samara-based art historian and curator Konstantin Zatsepin features texts by seven authors sharing their memories of the changing contemporary art scenes in six Russian cities: Voronezh, Yekaterinburg, Krasnodar, Krasnoyarsk, Rostov-on-Don, and Samara. Although it is not specifically devoted to self-organized initiatives, it does show how they shape the local cultural scene: in the absence of institutions, galleries and market, it is artists and curators who create the infrastructure they need for their work. “Working in culture in the regions is hard: you are always torn between the options of leaving or staying and trying to change the place — transform it into an environment that can produce and generate, and develop on its own,” Zatsepin says. “You need to transform the apathetic crowd into a productive artistic community.” This means starting self-organized initiatives to become proto-institutions like Voronezh Center for Contemporary Art, Krasnodar Institute of Contemporary Art, and Turnichki contemporary art lab in Rostov. Creating an open and flexible system of management on the one hand, these initiatives act as substitutes for big institutions on the other, hosting lectures, offering an education program and supporting new initiatives and institutes. E.I.

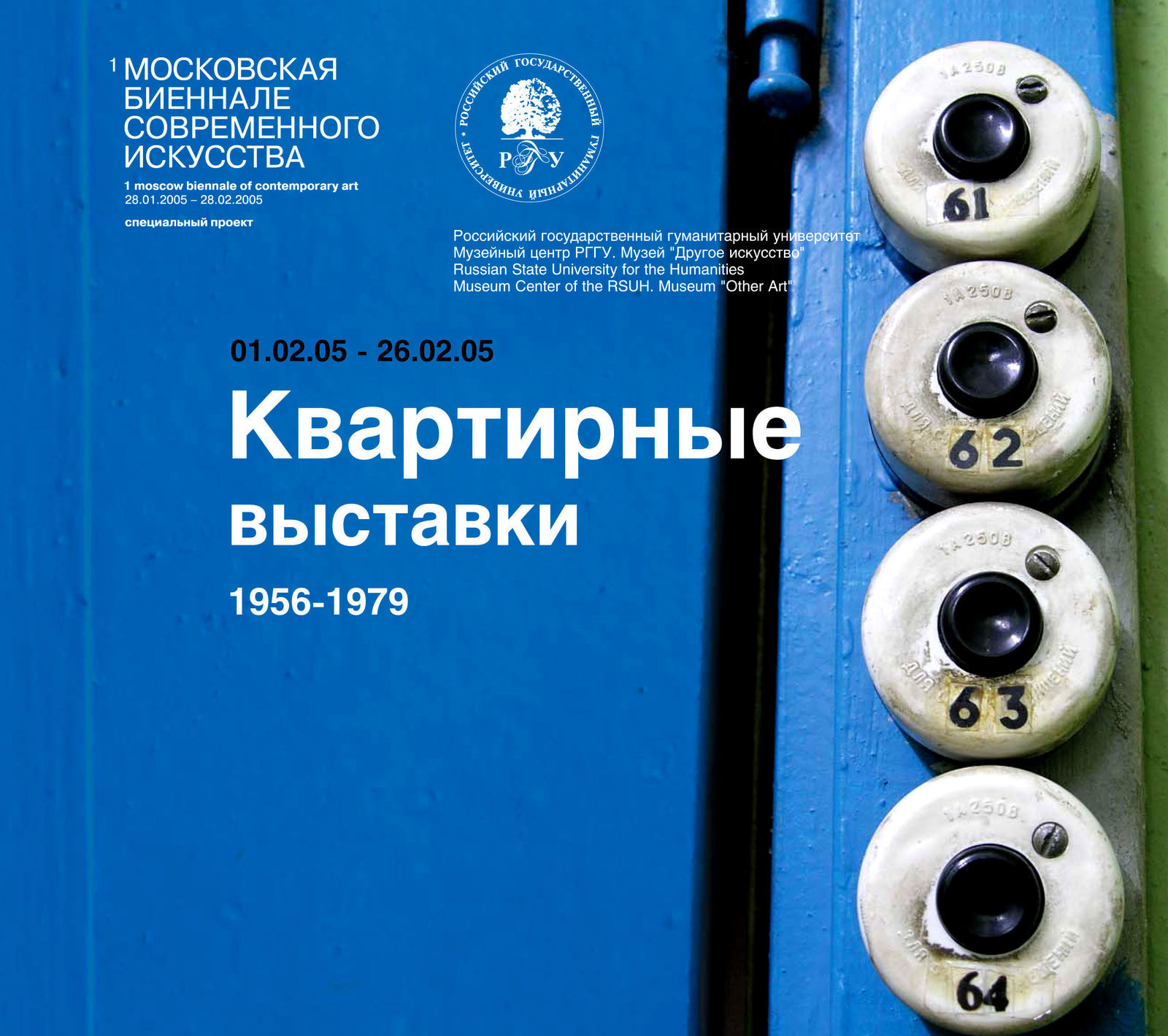

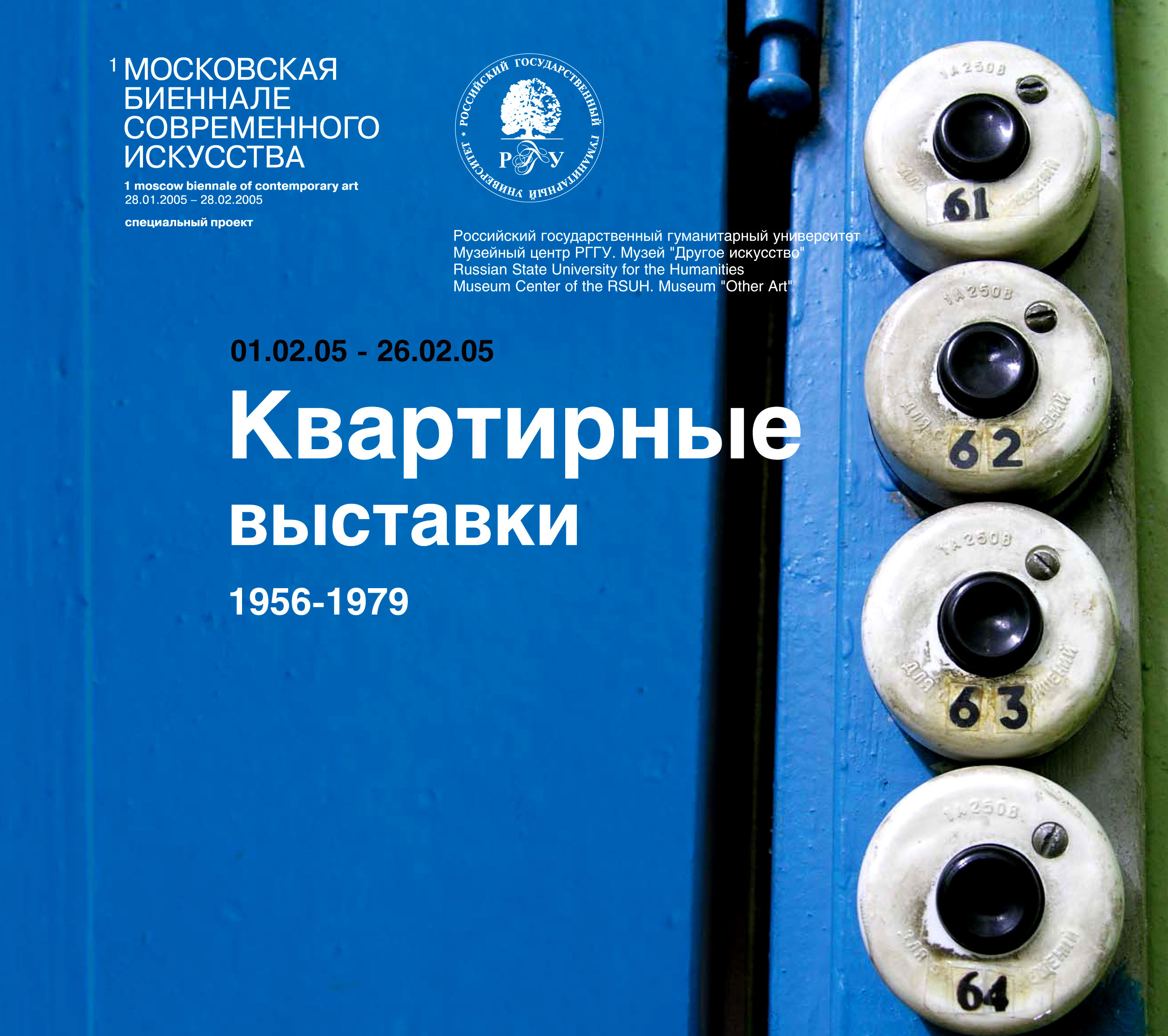

Kvartirniye vystavki. 1956–1979 (Apartment Exhibitions. 1959–1979), exhibition catalogue

Moscow: Muzey «Drugoye iskusstvo», Muzeinyi tsentr RGGU (The Other Art Museum, Russian State University for the Humanities), 2005, 26pp.

Kvartirniye vystavki. 1956–1979 is a catalogue for the eponymous exhibition that made up part of the First Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art in 2005. This very slim publication of just over 20 pages was one of the earliest attempts to analyze the phenomenon of apartment exhibitions as the main platform for underground art in the USSR. Curators Yuliya Lebedeva and Oksana Sarkisyan look into the history of apartment shows, starting from the late-1950s exhibitions in the apartments of composer Andrey Volkonsky and artist Vladimir Slepyan, to analyze the semiotics of the communal spirit on the Moscow underground art scene.

The catalogue features archival materials and a timeline of events up until 1979 (which means that the 1982–84 APTART gallery and the first Moscow squats are not discussed). One of the sources for the timeline was Leonid Talochkin’s archive, acquired by Garage in 2015. V.L.

Yarmarka khudozhestvennykh soobshestv «Universam» (Universam Art Communities Fair), exhibition catalogue

Moscow: Publisher?, 2009, 62pp.

Universam catalogue is a document of a truly unique event in the history of Russian contemporary art: a fair organized as a platform for communication and exchange of ideas between artists’ communities and self-organized initiatives, instead of selling art.

Drawing on the example of the Swedish Supermarket fair, Maksim Ilyukhin organized Universam as an alternative to two big institutional events held at the same time: the 3rd Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art and the Art Moscow fair. Taking part in the fair were artist-run initiatives: the exhibition space at Alexandr Povzner’s studio in Armyansky Lane, Voronezh Center for Contemporary Art, ABC Gallery, ARTStrelka-projects, Cheryomushki apartment gallery at Kirill Preobrazhesky’s place, and his VIDIOT video magazine.

Fully funded by its participants, Universam featured projects for future shows and works instead of actual artworks. The catalogue provides detailed descriptions of the projects and includes a brief but important text by Maksim Ilyukhin and a foreword by artist Stas Shuripa. E.I.