Viktor Pivovarov. Interview with myself

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art is proud to present the most exhaustive solo exhibition of Viktor Pivovarov’s work for 12 years.

One of the key representatives of Moscow conceptualism, Pivovarov, along with Ilya Kabakov and Andrei Monastyrsky, shaped the Russian underground art scene in the postwar years. The exhibition The Snail's Trail, which opens just before the artist’s 80th birthday, is organized as a romantic journey in 11 chapters. It begins with Pivovarov’s earliest works from the mid-1970s and culminates in his latest series of paintings. Pivovarov’s genius is multifaceted: the exhibition shows him as a painter, a book designer and illustrator, a theoretician, the inventor of conceptual albums, a memoirist, and a writer. Exclusively for GARAGE, he interviews himself.

Viktor Pivovarov

Tenderness, 2003

Oil on canvas

Collection of the artist

Your exhibition “The Way of the Snail” opens in March 2016. What does the title mean?

“The Way of the Snail” is the title of a painting that will not be exhibited in this show. Being what it is, it could never be in this show. It’s a paradox, I know. However, in a happy coincidence—or maybe it isn’t a coincidence—The Way of the Snail and seven other works will be exhibited at the Pushkin Museum, in parallel with the exhibition at GARAGE.

It’s quite strange for the title of an exhibition to refer elsewhere. Is there something in the exhibition to justify the title?

The exhibition ends with a poem featuring a snail. I can say without false modesty that I am very proud of this poem. It’s very brief:

A snail has left a trail in the sand

A trajectory of its flights

A narrow path

Laid by the mother-of-pearl

Button polisher

This seems a somewhat far-fetched justification.

It depends on how attentive the viewer is. To me, the image of a snail with its shell coiled inward is a metaphor for the entire exhibition and for an introvert’s mind, spiraling deeper and deeper into the cosmos that is the human being.

Viktor Pivovarov

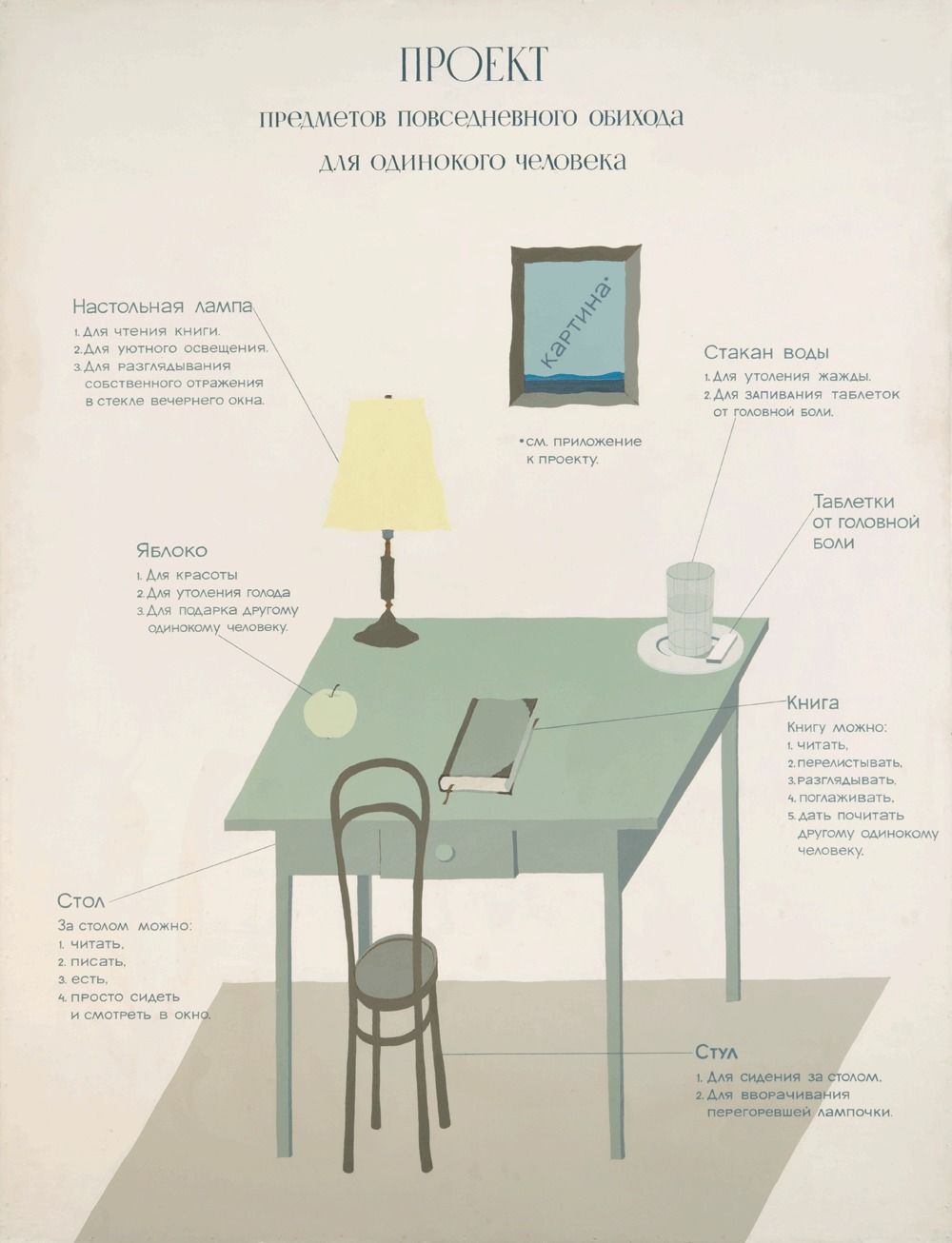

Project of Household Items for a Lonely Person, 2016

UV coating on acrylic

176 × 136

Courtesy of the author

A human being—how proud it sounds! Do you agree with that statement?

It’s impossible to answer that question! “A human being” can stand for a million different things. If I were asked to define “a human,” I would be at a loss. It depends on your perspective. As a social being, the human is disgusting; psychologically, the human is pathetic; with regard to sex, the human is determined; as a creative being, the human knows no limits. When I speak of exploring the depths of the human mind, I’m thinking of the mother-of-pearl button polisher—a phenomenon far removed from so-called reality, a product of the imagination, an artist’s dream.

Does a contemporary audience need this kind of human being?

That’s a question only the audience can answer. It would be irresponsible of me to anticipate their reaction. I can only offer the rules for the game, in which there are no winners or losers. The audience is free to accept or reject them.

What is this game? What are its rules?

I suggest that we envisage the exhibition as a journey: a journey into the snail, into ourselves, our childhood, our experience, our fears and doubts. I, as the artist, take a risk, since the easiest option for the audience is to treat this journey as mine, and not as their own. If that happens the audience has not accepted the rules of the game and I, as an artist, have failed.

If such a reaction would be your failure, does that mean you work for the audience?

The audience is unreliable, capricious, and unstable in its opinions and desires. My customer is different: I work for the institution. I do not mean a Supreme Institution, which, I believe, does not care about art. My institution is Culture: the Tower of Babel that has been built over centuries, bit by bit, despite persecution, corruption, trials and tribulations, without a goal, without a plan, and nobody knows why and what for. Only this amorphous institution, with no boss and no management, will hold me responsible. The mother-of-pearl buttons I offer it must be well polished.

Will Culture not eventually share the fate of the Tower of Babel?

Anything can happen. But I don’t think that will, as it was the Supreme Institution that intervened in the construction of the biblical tower and confused the common language. It appears to me that the Supreme Institution was showing how transitory a tower of clay and rock is, and how only a tower built of languages can help us attain what cannot be said in any particular language.

If you answer only to the institution of Culture, why are you showing your buttons to the public?

That’s the paradox. It would seem that I don’t need to show them. I have often said that a painting can stay forever in the artist’s studio facing the wall. What really matters is that it has been painted, and it hasn’t been not painted. The fact that it’s facing the wall does not change the fact that it has come into existence. But in terms of Culture, this is not enough. The painting’s existence is still the most important factor, but it is not the only one. Culture also involves all the fuss around it—vanity fairs, Art Basel fairs. This is an integral part of Culture, but it is also how Culture gets hoisted by its own petard and struggles to overcome false values and opinions. Sometimes it doesn’t—and so the imaginary Tower of Babel keeps growing on rotten bricks.

You haven’t answered the question: why exhibit your work?

Because the Institution demands it. That is, of course, if we exclude my own vanity.

Viktor Pivovarov

Presentiment, 1977

Enamel on fibreboard

Courtesy of Museum of Avant-Garde Mastery (MAGMA)

Can you sum up the exhibition?

I will try to do that in the form of an opera libretto. It will be both straightforward and corny, which is typical of the genre.

Overture

The exhibition opens with the series Seven Conversations, which sets the tone for what follows. By the way, this series has been exhibited in Moscow only once before: in 1979, it was featured in the Color, Shape, Space exhibition at Malaya Gruzinskaya. In the years that followed it fell apart—pieces ended up in different collections—and I feel very fortunate to be able to reassemble it now. The Garden album—an image of a fantastic, speculative garden—is another theme in the overture, which accompanies the audience throughout the journey.

Act One

An offstage voice, from a long-lost childhood: “This is Radio Moscow. The time is 7:30pm, and you are listening to Theater Speaking.” The act starts with the hand: the hand of a teenager changing a lightbulb, Basya’s hand holding a stick with a sphere, a hand crumpling a sheet of paper; and finally, the hand at the end of the Long, Long Arm with an ant and a man with a dog walking on it.

Act Two

There is an obvious time gap since the end of Act One. The theme of loneliness emerges. Projects for a Lonely Man suggests an austere, extremely modest and strictly scheduled life of contemplation, inner work, and indifference toward the joys and pleasures of the world: a theme that can be described as “secular monkhood.”

Metaphysical Composition introduces a new theme. Abstract drawings on paper scraps look like the scattered scribbles of Doctor Faustus, carefully collected and preserved by his humble pupil.

Act Three

The day’s travels are over and day turns into night. You never know what night will bring. The night grows darker. Darkness envelops the cozy room of the old Dutch ladies in Antony Pogorelsky’s Black Hen. Shining in this darkness are the lines of Yuri Mamleyev’s story about the inescapable fear of death. The fear of death is not the only fear that haunts us in the dark of the night. The Sutra of Fears and Doubt lists a great number of other fears and reservations. The sutra is a 10 meter-long scroll, imitating sacral objects like the Torah or old Chinese scrolls, and consists of two parts. The first contains 228 fears, but most of it “has been lost.” The second part, which contains 77 kinds of doubt, was “found intact.”

Act Four

June–June is something like the pages of a diary. The night is over and the word “day” shines through the word “diary.” The entries are very brief: there are only two words on each page: summer–sky, grass–clouds, eyes–hand, funny–funny, wind–evening, silence–shimmer. Two words, two circles, two horizontal lines. This diary is about the encounters of two. And a vertical line, separating the two halves. Could these be the two halves that Plato’s Aristophanes speaks about in the Symposium? “Each of us when separated, having one side only, like a flat fish, is but the indenture of a man. He is always looking for his other half…”

Our encounter with Plato was not mere coincidence. Eidos is one of Plato’s key concepts and the main theme of Act Four. Here you will find eidetic figures and eidetic landscapes, as well as more elaborate compositions such as Moscow Gothic and Eidos with a Dog. The idealist connection between the human and the dog (both are easy to recognize, even though the image is not a realistic one) implies two things. First, that the human and “the rest of nature” were originally conceived as two parts of the whole. Second, that “the rest of nature” needs a human’s care and tenderness (Eidos with a Dog, Tenderness, Eidos with Three Birds).

Intermezzo

Imagine an experiment where a human vanishes “behind the horizon of unknown space.” Scientists try to regain contact with him and finally succeed. What we hear is the recording of a conversation between the scientist asking questions and the person behind the horizon of unknown space answering. The vanished person tries to provide all the answers, but they tell us no more than his silence would.

Finale

The climax—in a major scale—takes place in the gardens of Monk Rabinovich. The garden theme from the overture becomes the main theme. The gardens of Monk Rabinovich have no trees or flowers—they are “gardens of culture”—speculative, abstract gardens of ideas. Their main horticultural crop is a circle, which symbolizes completeness, harmony, and infinity. It points to the fact that these are transcendental, celestial gardens. At the end is the poem about the snail.

Viktor Pivovarov

Say uh-h-h!, 2010

Assemblage, glass

Courtesy of Museum of Avant-Garde Mastery (MAGMA)

Speaking of the snail and the Pushkin Museum show—what is that about?

It's not exactly an exhibition—the Pushkin Museum will show The Lost Keys, my series of eight paintings that allude to the old masters: for example, four of them are inspired by the works of Lucas Cranach the Elder. I partially reproduced the old masters’ spaces and narratives, and I used the same media. These are my most recent works. Seeing them exhibited together, and in the Northern Renaissance galleries (which I love), is a great and unexpected adventure.

I recently saw a documentary on the famous Czech choreographer Jiří Kylián. Anyone interested in ballet will know his name. In this documentary, Kylián speaks of how he started out in classical ballet and how he loves it. Classical ballet, he says, is for fairytales: Swan Lake, The Nutcracker Suite, Giselle. But it’s no good for Beckett. A contemporary worldview demands different gestures, different rhythms—even a different body.

Can this be applied to contemporary painting? It’s hard to say. First, because the art of previous centuries is not limited to fairytales. We have Michelangelo, Grünewald, and Rembrandt—the depth and drama in their works is timeless. Is their “dated” visual language relevant for a 21st-century audience? Is Rembrandt’s language good for Beckett? Unlike in ballet, the answer is yes. But—and here I agree with Kylián—Francis Bacon’s language would be better.

However, the temptation to try to speak the language of Bruegel and Cranach was too strong. I couldn’t resist it.

Viktor Pivovarov

Viktor Pivovarov was born in Moscow in 1937. He graduated from the Kalinin Moscow College of Art and Industry in 1957 and the Moscow Polygraphic Institute in 1962. Since 1982, he has lived and worked in Prague.