Word (Nec)romancer

Writer and curator Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer looks at the use of text in Raymond Pettibon’s work.

[…] Pettibon’s practice is so consistently scattershot, so single-mindedly pluralistic and all over the place, such an unrelenting spray of disjunctive flashes and wild outbursts, that strong patterns eventually must emerge across the field, as they do throughout all nature. Individual drawings amass into swarms that together exhibit new forms of collective behavior. More on nature: “When I hang a show, for the most part, it’s usually just as well to put up the drawings randomly, because that’s the nature of the work. There are dissociations and attachments and the mind will fill in the blanks.”1 All-over-ness stimulates connectivity and logic fills any breach, instinctively and compulsively; the point being, randomness may not be as easy to achieve as it looks.

The drawings grow out of note-taking, note-keeping, and note-hoarding elevated to heroic heights. Like an exploded notebook, expressing high-velocity release and tearing apart, mental debris blasts across any paper surface, the studio floor, and the gallery walls.

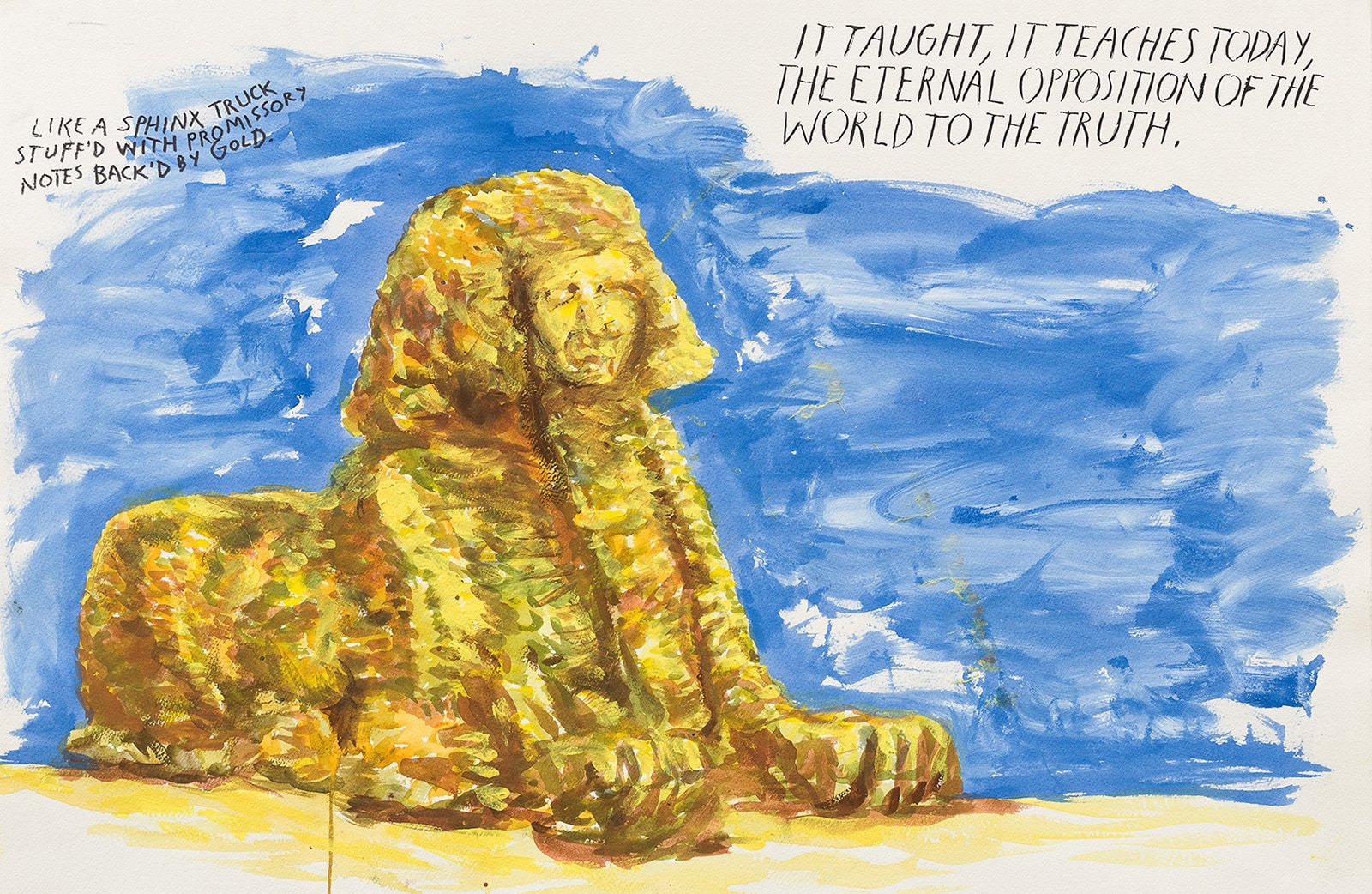

1.jpg)

Raymond Pettibon

No Title (It taught, it…), 2003

57.1 × 76.8 cm

Pen and ink on paper

Courtesy David Zwirner, New York

The artist cares not that it’s already been said. In fact, he loves literature’s already-said-ness, maybe its best part—a point of mutual identification, contact, and commonality with a lineage of past Homo sapiens thinkers. (Pettibon prefers dead authors to those living.) And so much has already been said. Awareness of the archive’s vastness comes up early and comes on hard—such unfathomable enormity can either lead to a dead-end, cul-de-sac feeling of paralysis or to a feeling of liberation that enables the artist to work, draw, and write free of pressure. I mean, originality is not only not a new idea, I’d say it’s rather obsolete. Risk of redundancy will not stop the living. Redundancy is living. I, for one, get turned on by my own insignificance.

“[…] It’s a dialogue with the dead, with other writers, that’s what it is and any- one who has any background in literary history understands that. One of my models, Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, is more a work of editing than it is of original writing.... You know the old cliche “The great writers steal, the other ones borrow?” That goes without saying.”2

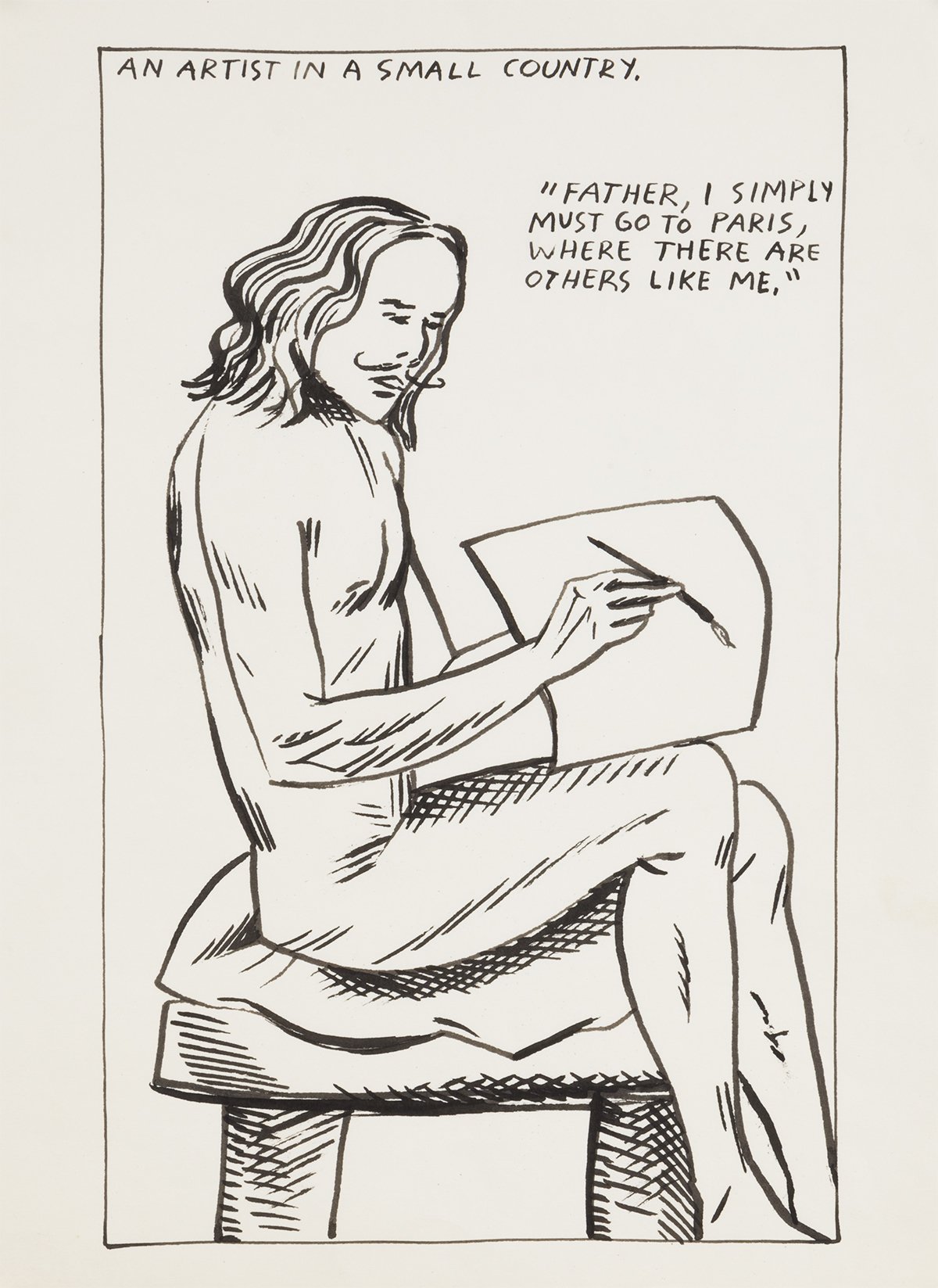

Raymond Pettibon

No Title (An artist in…), 1986

35.6 × 27.9 cm

Pen and ink on paper

Courtesy David Zwirner, New York

The practice of seamlessly and consistently integrating other writers’ words among his own in the form of verbatim or approximately quoted passages (he estimates about a third of his text is borrowed) is a multivalent proposition, accomplishing many things: It brings in a varied chorus of other voices, which is a way to put oneself in relation to a group of chosen others—to form a disembodied community. It’s a way of covering an author the way singers cover songs, bringing their style to bear on the rendition. It turns monologue into a kind of dialogue, relating his drawings to his parallel scriptwriting and filmmaking practice. It’s a way of speaking through others, dispersing and expanding identity beyond physical limitation.

[…] More than write it, Pettibon draws and paints text. Rare exceptions aside, language must come out, like the pictures, in his own hand. Handwriting expresses the timbre, pitch, and mood of voice; font and graphological style capture personality and identity.

Drawn out, his print is expressive and, considered in 2016, signals something other than “efficiency” or Word doc or professionalism and something more like care—lettering as tender form-making, or as a drawing from 1989 pro-fesses, I WRITE IT DOWN, EACH WORD, LOVINGLY.

[…] Sometimes cursive flows, but mostly Pettibon paints all-caps block letters in thin but solid black strokes. This scrawny capitalization has become his hallmark, his brand’s graphic identity: “To the public, my lettering is the most recognizable, identifiable part of my art, whether or not they actually read the text in the work.”3

“[…] I’m way behind in the work I’ve already set myself up for. I’m spread too thin.”4 Lack of focus, attention deficit, and feeling “spread thin” is increasingly a cultural, if not species-wide, epidemic, one with as-yet-unknown consequences, possibly terrifying and possibly electric. As Frances put it in that 1997 interview with Pettibon, “[t]here is a sense of so many books being open at once or something, it’s as if you like to have, like, uh, sort of God! I don’t know how to describe it but just to say like all books open, like so many things all open at once.”

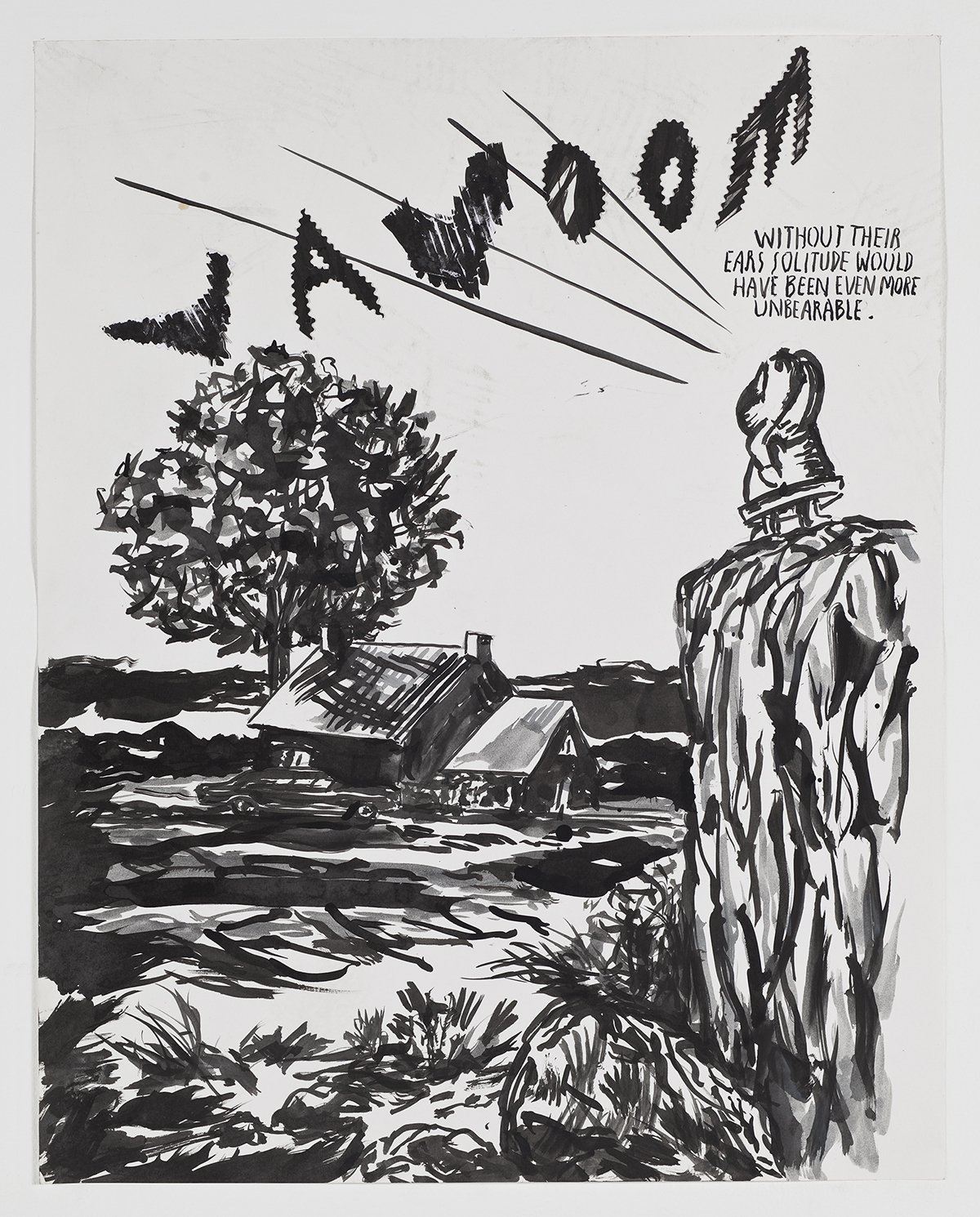

Raymond Pettibon

No Title (Without their ears…), 2010

61 × 48.3 cm

Pen, ink and gouache on paper

Courtesy David Zwirner, New York

[…] Of all Pettibon’s metaphoric proxies, from surfer to baseball player to superhero to penis, I prefer the authorial ones and the little boy with a monster hole in his head the most. Vavoom says “Vavoom.” He always says “Vavoom,” he only says “Vavoom.” Just one word, but oh what a big, big word. And he is the best at saying “Vavoom:” “It’s the only word he needs. It kind of fulfills all of his needs of expression and in my hands it usually becomes very literary. It’s sort of preoccupational with me, and because it’s just one word it becomes very liberating in the sense that you can read so much into it...harmony or cliche or figure of speech; it’s anything you want it to be.”5 Word and name coincide; identity is boiled down to and equated with that singular utterance for which he is known—or conversely, he is logos brought to life, the word made flesh. He is a magical invocation: mantra and motto, incantation and brute affirmation.

[…] Textual voices accumulate over time. Duration matters; moods shift as circumstances develop from day to day, month to month, minute to minute. Fortunes fluctuate, wars are waged, governments change hands. Drawings build and words gather slowly, often over the course of many years: “I’ve been at this for a long time, and I have voluminous amounts of unfinished work in the studio. They’re not all finished at one pass at the drawing board. So when I finally sign the work on the back...do I date it 2011, or 1989 to 2011?”6 This makes it tricky to pin the drawings down in time or chronology—and I cling to such difficulty. I love that there are very long delays between the beginning and completion of a work, confirming the primacy of the whole practice, as a function of time, over any particular piece. The supreme achievement, the insane passion, is the sustained dedication to a life of reading and drawing, each drawing a mere signpost pointing that way.

This is an extract from the exhibition catalogue A Pen of All Work (New York: New Museum/Phaidon, 2016), which is available from Garage Bookshop.

The material was published in Garage Gazette 2017 issue.

1. Raymond Pettibon, interview by Grady Turner, “Raymond Pettibon,” BOMB, Fall 1999, 42.

2. Pettibon in Frances Stark, This Could Become a Gimick [sic] or an Honest Articulation of the Workings of the Mind, ed. João Ribas (Cambridge, MA: MIT List Visual Arts Center, 2010), 43.

3. Pettibon, interview by Kristine McKenna, Alack (for to no other pass my verses tend), by Raymond Pettibon, Kristine McKenna, and Ed Hamilton, edition of 20 (Venice, CA: Hamilton Press, 2009), 7.

4. Ibid, p. 6.

5. Pettibon in Ulrich Loock, “Interview with Raymond Pettibon,” Raymond Pettibon, ed. Ulrich Loock (Bern: Kunsthalle Bern, 1995), 28.

6. Pettibon, 2011 interview by Mike Kelley, in “By Way of Norman Greenbaum,” in Raymond Pettibon, ed. Ralph Rugoff (New York/Los Angeles: Rizzoli/Regen Projects, 2013).