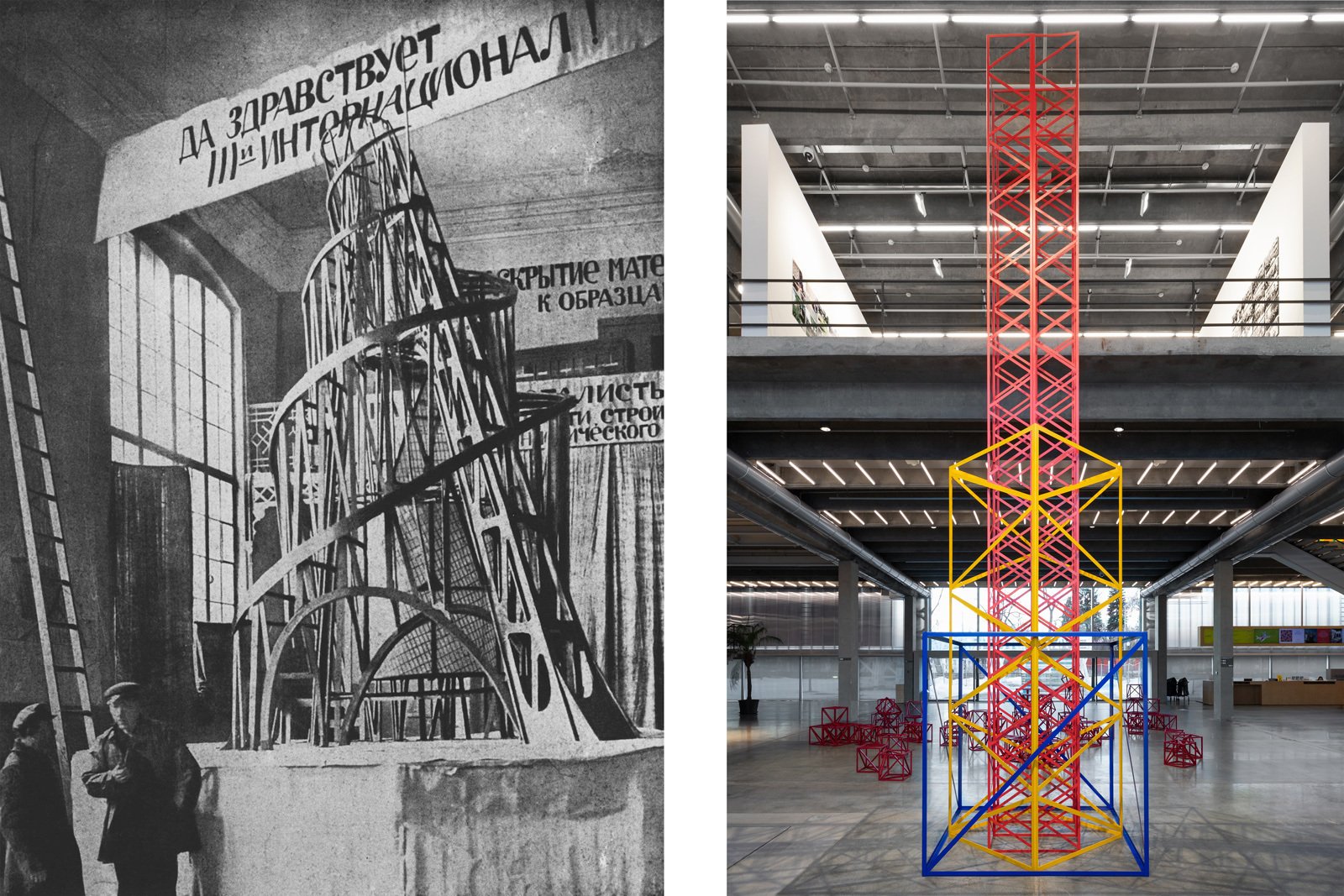

Rasheed Araeen. Homage to Tatlin, 1968/2019

Especially for Garage, Araeen developed an Atrium Commission, producing a sculpture he first envisaged in 1968. In a gesture that puts the artist in dialogue with the glorious and troubled history of the Russian avant-garde, Homage to Tatlin directly references Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the 3rd International, suggesting a kinship of non-Western modernities.

In the fifty years since Rasheed Araeen made the first small-scale model of Homage to Tatlin in 1968, his practice has undergone many transformations and the artist has been involved in the making of numerous important exhibitions and publications.

Today, the 7.5-meter sculpture Homage to Tatlin embodies Araeen’s very personal vision of the formal and political ambitions of the Russian avant-garde. Working within a broad cultural context, Araeen sees the avant-garde, along with minimalism and Islamic interlocking patterns, as episodes in the “journey of an idea,” in which geometry was used to produce a situation of equality between the artwork, the viewer, and the artist (and in the future, perhaps, a situation of political equality).

To understand the interplay of historical influences behind Homage to Tatlin we need to look back at the history of the project for the Monument to the Third International, also known as Tatlin’s Tower. In 1919, the People's Commissariat for Education commissioned Vladimir Tatlin to design a monument for the Comintern (or the Third International)—an international organization of communist parties similar to the UN. The 400-meter tower designed by Tatlin was to contain four large geometric structures, each with a particular function. A cube at the bottom was intended for large meetings and conferences; a pyramid above it would house the Comintern’s executive organs; then followed a cylinder containing an information center with printing presses and a telegraph; and a hemisphere, whose function is today unknown but which according to some sources may have been designed to hold radio equipment.

The first 4-meter model of the monument was exhibited in Tatlin’s studio in Petrograd in November 1920 and later at the House of Unions in Moscow, as part of an exhibition that reviewed the achievements of the young Soviet state for the 4th All-Russian Congress of Soviets. Writing for Pravda newspaper, journalist and poet Mikhail Koltsov described the Tower as an “enormous brain-twister of a thing.” In 1925, a new model was unveiled at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris. Both models produced by Tatlin were lost and from the late 1920s Tatlin’s contemporaries and researchers could only learn about the project through photographs. Erased from the culture during the era of Stalinist Socialist Realism (1932–1953), the tower did not resurface in Soviet or European publications until the 1960s. In 1961, two photographs of Tatlin’s Tower were featured in the exhibition Movement in Art, curated by Pontus Hultén and shown in Amsterdam and Stockholm. In 1968, Hultén commissioned a reconstruction of the monument for Tatlin’s retrospective at Moderna Museet. From the writings of the time, we know that in the 1970s and 1980s a model of the Tower was displayed on the balcony of London Polytechnic. Araeen, however, had seen it before, in Camilla Gray’s seminal 1962 book on the Russian avant-garde, The Great Experiment: Russian Art 1863–1922. He quickly responded to the egalitarian potential of the structure with his Homage to Tatlin (1968), which until the exhibition at Garage existed only as a project for a large sculpture.

Tatlin’s Tower has been compared to Eastern architecture since it was first presented to the public. In the book Russia: The Reconstruction of Architecture in the Soviet Union (1930), the main critic of the project among Russian avant-garde artists, Malevich’s pupil El Lissitzky, wrote that Tatlin borrowed the helix shape of his structure from the pyramid of Sargon II of Assyria in Khorsabad (Iraq).

Soviet artists were fairly familiar with the art of Ancient Assyria and Egypt, but less knowledgeable about Islamic art. However, in the 1980s, after the publication of several books on the art of Islam, architectural historian Andrei Ikonnikov suggested a closer parallel: the Malwiya Tower of the Great Mosque of Samarra (Iraq), built in 848 during the reign of the Abbasid caliph Al-Mutawakkil, at a time widely believed to be the golden age of Islam. In recent articles, Rasheed Araeen often quotes authors of the period, such as Al-Biruni and Ibn Sina (Avicenna), in order to subvert the modern Western monopoly on rationalism and enlightenment.

Ikonnikov saw the helixes of Tatlin’s Tower and the Malwiya Tower as symbols of the “continuity of time and development.” Alongside its symbolism, which does not quite belong to its historical context, the Malwiya Tower was also revolutionary in terms of function. Today, Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International could be described as a unique information and education center with multimedia content. The hemisphere at the top of the tower was to become a radio transmitter broadcasting for the USSR as well as Europe. At the time it was built, the Malwiya Tower of the Great Mosque of Samarra, which was designed as a minaret, was a rare example of a new kind of sacred architecture, comprising the architectural and ideological centerpiece of the city. The Abbasid Caliphate (8th to 13th century AD) was an internationalist regime and aspired, as historian Robert Hillenbrand has pointed out, toward universal brotherhood of Muslims beyond racial differences. And, in another parallel with the strategy of the Soviet regime, this universalism came with the absolute power of the caliph and the disenfranchisement of religious minorities.

El Lissitzky saw in Tatlin’s use of multimedia, technology, and “utilitarian elements” a “childish lack of thought” and dismissed the project as a crowd-pleaser. The Tower is admired as a work of art, but not as an architectural project (Ikonnikov notes the impossibility of building it to include utilities). One might trace the development of Araeen’s idea from the Malwiya Tower (a work of architecture) through Tatlin’s Tower (a design at the intersection of architecture and art) to Homage to Tatlin, a work of art without utilitarian function. In Araeen’s work the two iconic towers are distilled into pure movement or, in the words of the constructivist artist Vladimir Stenberg, into an “engineering truth.” What it offers is not freedom of interpretation but freedom from interpretation: the experience of its color, rhythm, and movement is equally accessible to everyone, regardless of gender, race or age.