Why I am Not a Modernist

The article Why Am I Not a Modernist? was commissioned from Mikhail Lifshitz in 1963 by the Prague-based Estetika magazine. In 1966, it was republished in the East German art newspaper Forum and in Literaturnaya Gazeta in the Soviet Union, where it provoked an indignant response from readers, which was also published. Later the article became part of the anthology The Crisis of Ugliness (1968).

Having written this heading in the style of Bertrand Russell, my answer should be a formula just as concise. It won’t hurt to be sharp to the point of paradox. You have to obey the laws of the genre.

So, why am I not a modernist? Why does the slightest hint of such ideas in art and philosophy provoke my innermost protest?

Because in my eyes modernism is linked to the darkest psychological facts of our time. Among them are a cult of power, a joy at destruction, a love for brutality, a thirst for a thoughtless life and blind obedience.

Maybe I’ve forgotten something substantial in this list of the twentieth century’s mortal sins. Already my answer is longer than the question. To me, modernism is the greatest possible treachery of those who serve the department of spiritual affairs – la traison des clercs, as the famous expression of one French writer has it. The conventional collaborationism of academics and writers with the reactionary policies of imperialist states is nothing compared to the gospel of new barbarity implicit to even the most heartfelt and innocent modernist pursuits. The former is like an official church, based on the observance of traditional rites. The latter is a social movement of voluntary obscurantism and modern mysticism. There can be no two opinions as to which of the two poses a greater public danger.

If an author dares write on this subject so directly, he must ready himself for harshest of rejoinders.

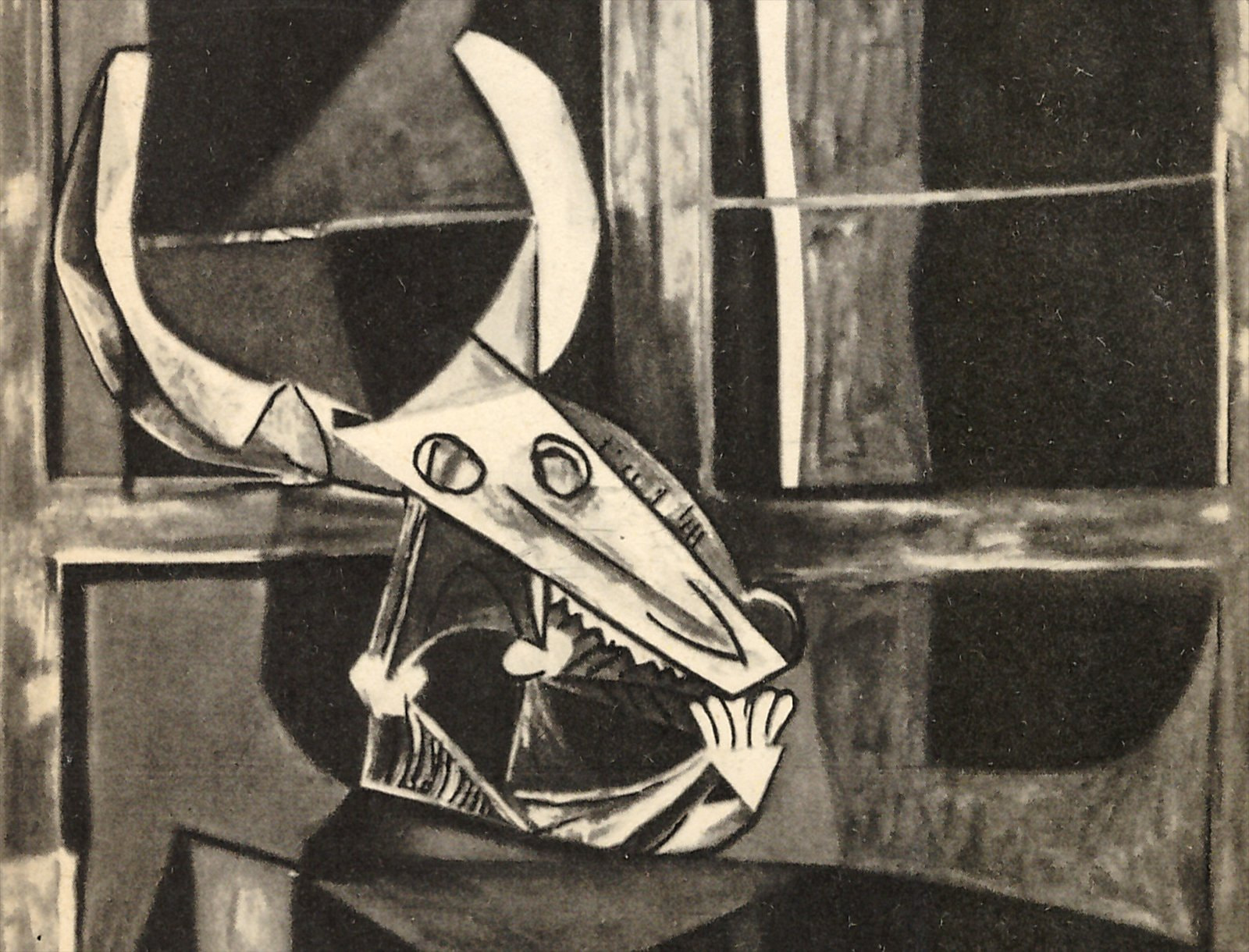

– How could it be? You’ve painted a portrait of a German storm trooper or an Italian blackshirt, and now you want to convince us of his immediate kinship to the sultry Matisse, the gentle Modigliani or the sullen Picasso?

Of course not. I wasn’t planning any attack on the moral reputation of these individuals. But still, let’s not deprive ourselves of the capacity for judging historical phenomena independently of how we judge this or that individual protagonist. Bakunin was a man famous for his revolutionary largesse of heart, but anarchism is the bourgeois character turned inside out, as Lenin put it.

Still, wasn’t it Hitler who persecuted the so-called modern artists, declaring them to be degenerates and pests? Didn’t you know that the bearers of the Western avant-garde’s refined aesthetic culture had to flee from the Nazis?

Of course, I know. But let me to soothe your disquiet with a little story taken from life. In 1932, the National Socialist government of the state of Anhalt closed the Bauhaus in Dessau, a famous hotbed of the ‘new spirit’ in art, presenting quite a vivid symptom of the Third Reich’s future cultural policy. The Parisian journal Cahiers d’art, published by Christian Zervos, an influential supporter of Cubism and later tendencies, answered this sad news from Germany with the following note (Nos. 6–7): ‘For reasons we cannot comprehend, the National Socialist party displays a decisive hostility to genuine modern art. This position seems all the more paradoxical since this party foremost wants to attract the youth. Is it acceptable to absorb all these youthful elements, so full of enthusiasm, vital force, and creative potential, only to once again return them to the lap of outmoded tradition?’

Ah, you still don’t get it, scumbag? Heinz, Fritz, come on, explain it to him!

And explain they did.

That is the actual picture of manners in Europe on the eve of Hitler’s Walpurgis night. How much grovelling is there in the note above, and how accurately it depicts the admiration for the false youth of barbarians that led to the cultural Munich of the 1930s. In the depths of their souls, the advocates of ‘genuinely modern art’ were infected with the same cult of vitality and spontaneous energy. It was the same wind that took them so far from the shores of the ‘liberal-Marxist nineteenth century’.

I understand that the editors of the Parisian journal are educated, refined people at a great remove from the demagogy of street-criers offering lessons in amateurish Heimatkunst. This was hardly what they had imagined as a world rejuvenated, freed of canons and norms. And of course they were hardly expecting the petty demons of literary bohemia and the boulevard writers to actually rise to power as they expounded the myth of the twentieth century in the language of Nietzsche and Spengler, diluted with the slavering of a rabid dog.

Nietzsche himself cultivated a deep disgust of the plebeian tastelessness of beerhall politicians, and no doubt he would have disowned his spiritual heirs. Spengler managed in his lifetime to forswear them from the position of a more respectable bourgeois Caesarism… The logic of things, however, acts on its own. There is such a thing as retribution, and it is terrible. Speaking in a Hegelian spirit, Marx and Engels called it the irony of history.

You wanted vitality? You were fed up with civilization? You fled from reason to the dark world of instinct, you scorned the masses in their aspirations to the basics of culture, you demanded that the majority offer blind obedience to the irrational call of the superman? So, here you are, you’re welcome to all of what you have coming to you.

Here’s another strange story. In 1940, an elderly Henri Bergson set out in the company of his nurse to register with the German occupation authorities in Paris. They say it was the last time he went outside – the world-famous thinker died before he could reach Auschwitz. Who can say that this man wasn’t talented and honest somehow? There is enough proof in that he wanted to share the fate of his people, even though he had long since broken with Judaism.

Still, one fact remains incontestable. Henri Bergson was the leader of a new direction in philosophy that accomplished a far-reaching re-evaluation of values in the early twentieth century. He was one of the first to put checkmate the king, to raise the question of reason’s disavowal of its inherited rights. Since then, everything changed in the realm of ideas. The barons of vital power and the active life took centre stage. The price of suffering declined, and brutality became a token of noble character. The countless followers of Bergson and William James were ready to embrace the ideals of violence well before the First World War, with very different figures already visible on the horizon. The hero of Henry de Montherlant’s novel Le Songe (1922) is out to ‘negate the mind and the heart’ when he shoots the first surrendering German soldier he sees in the face.

It goes without saying that the French were not alone in making such discoveries. On the contrary, an even darker evolution was underway on the other side of the Rhein. No one suspected that the weak ‘will to power’ of decadent thinkers would realise itself in the race laws of the Third Reich. What devilry was afoot to upset the game? It’s none of our business; it’s enough that it happened.

One could come up with quite a few more examples, but the one that best fits our historical subject is the fate of the German thinker Theodore Lessing, murdered by the Nazis in August 1933. It goes without saying that he had nothing to do with Nazism in his convictions, and he couldn’t have. Still, Lessing’s philosophy of history was one of a meaningless flow of facts and forces, set up to combat the ‘spirituality’ of modern culture and to polemicise against objective truth while calling for open mythmaking. All of these things entered the prehistory of Hitler’s Germany in one way or another. But that’s what you wanted, hapless Georges Dandin!

You might say that there is no direct connection between the teachings of Theodore Lessing and the murderer’s bullet. Of course there isn’t. Now nobody believes in the wisdom of providence leading us to our higher goal with rewards and punishments. Those are children’s fairytales. In the world of facts, everything follows the laws of scientific necessity. Yet still, the religious imagination has real causes at its root and presents a poor copy of actual relations. There is no such thing as providence. There is, however, the natural interconnectedness of things, from which a moral meaning is not entirely absent. And when this moral meaning appears unexpectedly in the fate of persons or entire peoples, we witness it as the birth of a tragedy, or, more often, a tragicomedy.

You will tell me that there is a big difference between the subtle, partially justified polemic of a thinker in his study against the boundless power of intellection, and the famous phrase from the Nazi writer Hanns Johst’s drama Schlageter: ‘Whenever I hear [the word] “culture” … I remove the safety from my Browning!’ Of course, the difference is huge. Everything is very complicated in this most complicated of worlds. Among the creators of the espirit nouveau in art and philosophy, some really did sympathise with fascism in its different guises: we know their names, beginning with Marinetti. Others felt fascism’s heavy hand, as fate would have it. We also know that the national upsurge of a people often goes together with the Sturm und Drang of new tendencies in art. Such obvious facts are impossible to deny. Among the modernists, there are individuals of an impeccable inner purity, martyrs, and even heroes. In a word, there are good modernists, but there is no such thing as good modernism.

Matters here are the same as in the field of religion. The Catholic monks of the Basque country fought on the side of the Republic against Franco, and when Mussolini’s regime fell in Italy, some priests rang the Internationale from their steeples. These are our brothers; they are closer to our Marxist creed than all those political windbags who repeat Marxist phrases to further their careers. Many believers deserve respect. However, there is no such thing as good religion, since religion is always invisibly tied to centuries of slavery.

So don’t be in such a rush to liquidate the legacy of the Renaissance or that of the free-thinking nineteenth century. Don’t join the crowd of modern philistines in chanting that these are not will-o’-the-wisps in the dark night of the millennium, but flashes of distant lightning illuminating the path into the future. Don’t cast your gaze back to the new Middle Ages like the prophets of regressions. And if you do, don’t complain if they force you to believe in the absurd and tell you where exactly to find beauty, under blows or worse. That, after all, is the reality of spiritual primitivism.

You might say that my examples only concern the masters of theoretical invention, gentlemen who today enjoy less respect than people of the arts. Alright then, let’s turn to the artists themselves.

Picasso was unhappy that the revolutionary governments place such an importance on museums and the general enlightenment of the broader masses in the spirit of the classical legacy. In 1935, he told Christian Zervos:

The museums are so many lies, the people who occupy themselves with art are for the most part imposters. I don’t understand why there should be more prejudices about in the revolutionary countries than in the backward ones! We have imposed upon the pictures in the museums all our stupidities, our errors, the pretenses of our spirit. We have made poor ridiculous things of them. We cling to myths instead of sensing the inner life of the men who painted them. There ought to be an absolute dictatorship … a dictatorship of painters … the dictatorship of a painter … to suppress all who have deceived us, to suppress the trickster, to suppress the matter of deception, to suppress habits, to suppress charm, to suppress history, to suppress a lot of other things. But good sense will always carry the day. One ought above all to make a revolution against good sense! The true dictator will always be vanquished by the dictatorship of good sense … Perhaps not![1]

It is sad to read these lines, especially if one remembers that in 1935, there was already a totalitarian artist-dictator, or a failed artist, no matter. I mean Hitler, of course, whose biography we know. For some reason all dictators since Nero have imagined themselves to be very strong in the arts.

You tell me that this is not what Picasso wanted. Who would think otherwise? You can be sure that I appreciate Picasso’s political views and the nobility of his intentions. As for his worldview, he is careless in his thinking to say the least.

There is great danger in such invocations of forces capable of driving the mindless masses into a new realm of beauty by force. There is no such thing as enlightened despotism. Despotism is always unenlightened. Moreover, the stick always has two ends, and this is something we should never forget. If Picasso meant the Soviet Union with his ‘the revolutionary countries’, our society rejected the dream of a ‘total dictatorship’ in the field of the arts, thank god. While such phenomena are familiar from the past, they bear no relation to the principles of the socialist order. They are abuses of power, just like any other iniquity.

In the years of my youth, the modernists were very strong in revolutionary Russia, and they often resorted to violence without ever suspecting that they would have to bear the consequences themselves one day. It was only with great difficulty that People’s Commissar of Enlightenment Anatoly Lunacharsky could stem the tide of the ultra-left on orders from Lenin, who later reprimanded the former for being too lax. Once there was some sort of disagreement between Ilya Ehrenburg and the famous left-wing theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold, who headed the theatrical section of the People’s Commissariat of Enlightenment in the early days of the revolution. Unhappy with Ehrenburg’s aesthetic views, Meyerhold didn’t hesitate to call the commander of the guard to demand his interlocutor’s immediate arrest. The commander had no right to make arrests and refused. Ilya Ehrenburg remembers this in his memoirs as a pleasant joke, steeped in the foggy past, but it sends chills down my spine. I remember Meyerhold from later on, when the sword was already hanging over his neck, and I feel deeply and honestly sorry for the artist and the man. So many tragedies, and all of them full of bitter meaning! ‘We learn through suffering’, chants the chorus in Aeschylus’ Oresteia.

Ehrenburg presents the cult of power and destruction inherent to all modernism in the person of Julio Jurenito, who dreams of a bare humanity on the bare earth, and sees war and revolution as little more than steps to this long-cherished goal; the worse, the better. ‘The great provocateur’ of the writer’s imagination may have been unhappy with the moderation of the Russian communists, especially in matters of culture, but Lenin liked Ehrenburg’s novel. The figure of Julio Jurenito and his whole milieu reflected a force that he understood very well, deeming it the greatest enemy of communism, even if it played a certain role in the destruction of the old Russia. This force is petit-bourgeois spontaneity, capable of destroying and even razing the fundament of cultures like an act of nature, the breath of the desert, full of a great Nothingness.

This power is ever-changing and has many faces. Julio Jurenito killed himself, disappointed with Lenin’s desire to save the legacy of the past to further develop its positive values. But what if the ‘great provocateur’ had lived to a later time? Who knows, he might have turned out to be the right-hand-man of Ezhov or Beria. I could also imagine him as a patron of the arts, supporting pompous pseudo-realistic painting with pictures of banquets, receptions and other celebrations. Why not? Doesn’t the whole world now value such amateurish daubery as ‘modern primitivism’? Didn’t Henri Rousseau already drag up all the dredges of the petit-bourgeois soul? Isn’t he a modernist classic? Don’t the surrealists trace out the details of their works with a meticulousness that any academic painter would envy? There are possibilities for an as yet unheard-of modernism on the basis of the Victorian style, retaining all the features of nineteenth-century genre painting.

When you say that Hitler was a proponent of realistic pictorial forms, allow me to answer that this is untrue. First, there was plenty of ordinary modernist posturing in the Third Reich’s official art. Its fake restoration of real forms is often reminiscent of the New Objectivity movement of Munich in its inflated pathos and its striving to monumentality, soaked through and through with ideas of arbitrary lies. This is even more obvious in Italy, where Marinetti’s futurism took up a position as official art along with the artificial neoclassicism that emerged from the same decline.

Second, the social demagogy of reactionary forces always appropriates some of its mortal enemies’ outer traits. This is necessary to draw crowds and to attract ‘the man in the street’. It’s enough just to remember the name of Hitler’s party. There are many ‘socialisms’ that have nothing in common with the real content of this notion. Does it really follow that we should renounce socialism? An old legend says that Christ and the Anti-Christ look alike. And really, such optical illusions are no rarity in fateful moments of history. Woe to those who cannot tell the living from the dead! We first need to reject the outer analogies so readily used by the enemies of socialism when they confuse the illnesses of a new society with the purulent ulcers of the old world.

Third, the future is born in agony. ‘We learn through suffering’. Art must rise up out of the deep hole in which it now finds itself (as many authoritative witnesses of various directions recognise), and anyone who thinks there is any other way is simply a very nervous gentleman. The field of literature has been luckier than painting, if only because its strongest time is not so far from our own. The tradition of classical realism is still alive in literature, for which there is also some evidence in the works of contemporary Western writers popular in the Soviet Union (often more than at home).

Still, let’s get back to Picasso. To prove our loyalty, let’s compare him to Balzac. In one of his novels, the great French writer drew up a utopia of social Bonapartism that came true as a terrible caricature just in the moment after he died and Napoleon III came to power. The real course of history doesn’t follow orders; it will take a path of its own, and the only conclusion you might draw is that the initial idea needs a more concrete development, allowing one to draw a maximum use from history’s unexpected twists. As for ideas like that of the total artist-dictator who liquidates history to forcibly impose Cubism, abstract art, or some other modernist balderdash, it’s better not to have such ideas at all.

Picasso’s conversation with Zervos appeared in Nos. 7–10 of the Cahier d’art in 1935. When Zervos wanted to show the artist his notes, the latter answered: ‘You need not show them to me. The essential, in these times of moral misery, is to create enthusiasm. How many people have read Homer? Nevertheless everyone speaks of him. Thus the Homeric myth has been created. A myth of this kind creates a precious excitation. It is enthusiasm of which we have the most need, we and the young’.[2]

I have no desire to accuse Picasso of anything. All the more since he must have had occasion to hear much strong abuse from his fellow modernists. What is important to me is to mark the main features of the worldview we are offered as the lodestar of the future art – the renunciation of realistic pictures, which Picasso sees as an empty illusion, that is, deception, and the affirmation of a wilful fiction, designed to spark enthusiasm, that is, the conscious deception of mythmaking. For the lack of space we will leave aside the social causes that give rise to these strange, contradictory phantasms as they appear in the tide of forms created by ‘genuine modern art’.

Let’s just say that the main inner goal of such art lies in suppressing the consciousness of the conscious mind. A flight into superstition is the very minimum. Even better is a flight into an unimaginable world. Hence, the constant effort to shatter the mirror of life or at least to make it muddy and unseeing. Any image must now be given qualities of ‘unlikeness’. In the way, pictoriality recedes, eventually becoming something free of any association with real life.

The founder of surrealism André Breton once complained that the demon of real imagination is strong. Once it was enough to present a few geometrical figures on the canvas to avoid any associations. Now this is too little. The self-defences of consciousness are so refined that even abstract forms are reminiscent of something real. That requires an even greater degree of detachment. Hence, there appears anti-art, pop art, which largely consists of the demonstration of real things, enclosed in an invisible frame. In a sense, this is the end of a long evolution from real depictions to the reality of bare facts.

It might seem we’ve already achieved that goal: the life of the spirit has ended, the worm of consciousness has been crushed. Still, that is an empty illusion. The ailing spirit’s attempts to jump out of its own skin are senseless and hopeless. When reflection revolves around itself endlessly, it only gives rise to ‘boring infinity’ and an insatiable thirst for the other. If any phenomenon needs to be taken on its own terms, then ‘modern art’ is only comprehensible to a mind that has been initiated into this mystery. All else is either a naïvely pedestrian adjustment to the last fashion, or the unconscionable phraseology of interested parties wishing to smuggle their wares under a false flag.

Yes, ‘modern art’ is more philosophy than art. It is a philosophy expressing the dominance of power and facts on lucid thinking and poetic contemplation of the world. The brutal demolition of real forms stands for an outburst of blind embittered volition. It is the slave’s revenge, his make-believe liberation from the yoke of necessity, a simple pressure valve. If it were only a pressure valve! There is a fatal connection between the slavish form of protest and oppression itself. According to all the newest aesthetic theories, art’s effect is hypnotic: it traumatises or on the contrary blunts or calms a consciousness that no longer has any life of its own. In short, it is the art of a suggestible crowd at the ready to run after the emperor’s chariot. In the face of such a programme, my vote goes to the most mediocre, derivative academicism, since that is the lesser evil. But it goes without saying that my ideal lies elsewhere, as the reader can guess.

People who delight at the revelations of the kind conveyed through Zervos have no right to find fault with the theory of the ‘big lie’ in politics, the mythologies created through film, radio, and press, the ‘manipulation’ of human consciousness by the powers that be, and so on. The modernist never opposed such methods. On the contrary, their idea is mass hypnosis, ‘suggestive persuasion’, raising a rather dark enthusiasm, and not reasonable thinking and a light sense of truth. Modernism is a modern superstition, slightly insincere, much like the one in late antiquity that gave rise to the belief in the miracles worked by philosopher Apollonius of Tyana.

However, such superstitions are now asserted with the most modern means. One recalls Lev Tolstoy’s words on ‘epidemic suggestions’, spread through the printing press.

With the development of the press, it has now come to pass that so soon as any event, owing to casual circumstances, receives an especially prominent significance, immediately the organs of the press announce this significance. As soon as the press has brought forward the significance of the event, the public devotes more and more attention to it. The attention of the public prompts the press to examine the event with greater attention and in greater detail. The interest of the public further increases, and the organs of the press, competing with one another, satisfy the public demand. The public is still more interested; the press attributes yet more significance to the event. So that the importance of the event, continually growing, like a lump of snow, receives an appreciation utterly inappropriate to its real significance, and this appreciation, often exaggerated to insanity, is retained so long as the conception of life of the leaders of the press and of the public remains the same. There are innumerable examples of such an inappropriate estimation which, in our time, owing to the mutual influence of press and public on one another, is attached to the most insignificant subjects.[3]

We must factor in the coefficient of ‘epidemic suggestion’ whenever we talk about the miracles of modernism. Whatever Tolstoy might have seen has long since been eclipsed by modern advertising. In the old art, it was important to depict the real world as lovingly and conscientiously as possible. The artist’s personality more or less stepped into the background with regard to its output and thus rose above its own level. In the newest art, exactly the opposite is true: the artist’s work is merely a sign, a token of his personality. ‘Everything I spit out is art’, said the famous German Dadaist Kurt Schwitters, ‘because I am an artist’. In a word, it doesn’t matter what you make. What’s important is the artist’s gesture, his pose, his reputation, his signature, his sacerdotal dance for the camera, his wondrous acts, proclaimed for the world to hear. He can heal by the laying-on of hands, they say.

This new mythology has little in common with the one from whose depths art was born. The art of real primitives is far superior. Everything in it has the charm of awakening minds and hearts, everything promises to flourish as desired. There is much to learn from the Old Masters of our old Europe, from the Africans, or from the artists of the pre-Colombian Americas. But what will you learn? That is the main question. Goethe said that there is no returning to your mother’s womb.[4] As charming as childhood is, so savage is the adult’s desire to lay down the burden of thought and return to infancy. If you don’t see the onset of night as a fatal feature of the modern world, you must be against an art that draws from the Middle Ages, Egypt, or Mexico dark primordial abstractions, the happy absence of personal thought, ‘conciliarity’, as the Russian decadents of the early twentieth century put it, that paradise of educated souls, fed up with their own intellectuality, their own odious freedom.

The language of forms is the language of the spirit. It’s the same philosophy, if you please. For example, you see the bowed heads, humble eyes, and hieratic gestures of people dressed up in worker’s overalls or peasant jackets, you know exactly what the artist wants to say. He is seducing you with the dissolution of individual self-consciousness in the blind collective will, the absence of inner turmoil, mindless bliss – in a word, a utopia far closer to the one Orwell draws up in his caricature of communism than to the ideal of Marx, Engels, and Lenin. I feel sorry for this artist. Blessed innocence! Pray to your god that your higher mathematics never find their real model in the actual world. Then again, I can already see your dismay when the man in the peasant jacket finally awakens from his century of slumber and, one would hope, decides he no longer wants to pose in the role of an Egyptian slave subject to monumental rhythms and the laws of frontality. By the way, for the majority of people, museums are not ‘so many lies’ (as Picasso put it), since these people hardly suffer under a glut of culture. They want to be individuals.

Caesar fawns over the consecrated crowd, but the communist has no need of a crowd blinded by myths. He needs a people composed of conscious individuals. ‘The free development of each is the condition for the free development of all’, it says in the Communist Manifesto. This is why I am against the so-called new aesthetic, whose outer shell of novelty hides a mass of old, brutal ideas.

May Lenin’s teachings always be our banner. Their subject is the historical self-activity of the popular masses, and all Caesarism along with the attendant atmosphere of miracles and superstition are hostile to our idea. We stand for the combination of living popular enthusiasm with the clear light of science and an understanding of the actual reality accessible to any literate person, with all the elements of an artistically developed culture attained by humanity ever since the individual emerged from blind obedience to inherited ways of life.

So let them tell us tall tales of the happy land of Archaia and of the new primitivism of the twentieth century. Modern primitivism, to speak with Hobbes, is ‘a robust but malicious boy’, somebody you don’t want to argue with in dark alleyways. May Kafka – an intelligent but ailing artist – rise from the grave to write a bold allegory on the modern worshippers of darkness, including his own, like that of Capek’s tale of the newt who rejects conventions and tradition. As for me, I’ve had my fill of the twentieth century’s primitivism.

This is why I am not a modernist.

[1] Zervos and Picasso 1968, p. 53.

[2] Zervos and Picasso 1968, p. 48.

[3] Tolstoy 1906, pp. 98–9.

[4] Trans. note: There is no such direct quote attributed to Goethe. The reference here is possibly to one of Goethe’s proverbs: ‘In mother’s lap, in comfort’s glow, / The child his life would make; / Yet if to man he e’er shall grow, / The child must stir and wake.’