Comb in the Grass: Small Descriptive Models That Have Turned into Action

The project by Alexandra Sukhareva (b. 1983, Moscow) focuses on the Siege of Leningrad (September 8, 1941– January 27, 1944). In this research, the artist’s key concern is to explore the variety of channels and spiritual outlets through which people sought something to rely on in the face of the uncertainty.

The 872 days of the siege—or the blockade as it is also known—traumatized an entire generation, causing many events to be repressed in the collective memory. With sporadic access to information from the outside world in the first months of the blockade, the city's inhabitants began to look for alternative ways of understanding and constructing reality, which brought about a major shift in people's daily preoccupations and rituals. Sukhareva’s research focuses on documents of human experiences that show how hope can produce a different kind of reality, exploring the way we process information at the time of social convulsions.

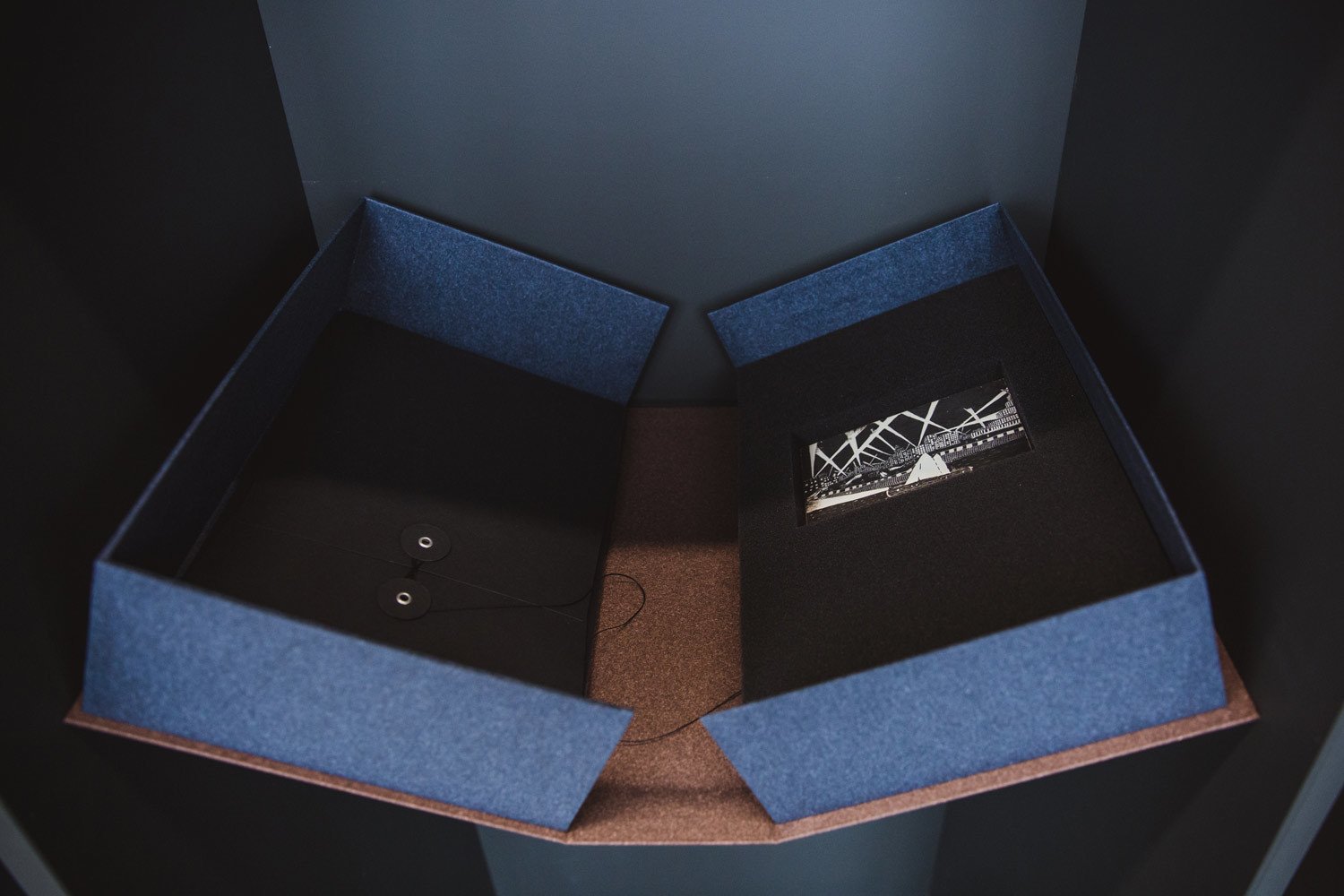

Since the launch of the project, Sukhareva has conducted extensive research in public and private archives and institutions, including the State Hermitage Museum; the Museum of the Defence and Siege of Leningrad; the Roerich Family Museum and Institute; the Central State Archive of Political and Historic Documents in St. Petersburg; the Moscow Theosophical Society; the Museum of Sadriddin Ayni in Samarkand; and the State Museum of the History of the Temurids in Tashkent. Many of the materials found in the process of research are gathered here in the shape of six folders or “volumes,” as Sukhareva refers to them. Each volume contains a selection of documents relating to one subject, person or event. Two of them will remain closed at this stage of the project and will be filled with the continuation of her research in the future. During the exhibition, Sukhareva will lead a number of tours and talk about her research and the story behind each volume.

The first volume tells the story of Olga Obnorskaya (1892–1957), a member of the group of theosophists who lived in the village of Guarek, near Sochi, in the 1930s. Obnorskaya was a medium and continued hearing voices and seeing visions after she left Guarek, including while living in besieged Leningrad. The second volume examines objects that belonged to Helena Roerich (1879–1955): her brooch and a weathered silk rose, which were among the objects that witnessed and survived the siege in the house of Lyudmila Mitusova. The third volume is centered around a drawing made by schoolboy Misha Mironov, who walked out of the besieged city in 1941 in an attempt to be reunited with his relatives in Moscow and was never heard from again. The fourth volume opens with a late-eighteenth-century Masonic image that entered the collection of the State Hermitage Museum in 1941. The meaning of the image is not clear even today, but it is surprisingly contemporary.

The exhibition also features an object the artist describes as “impossible:” a Ouija board that people used to talk to spirits.

The object does not seem to belong in the Leningrad of the early 1940s, however the artist inserts it into the context of her research, creating a distortion of the historical narrative that allows the trauma to manifest itself.

Initiated in 2016.

1.

Olga Obnorskaya was a talented medium. During her stay in Guarek, she wrote down her first “dictations," which were similar to those received by the well-known occultists Alice Bailey and Helena Blavatsky. She continued to receive them for the rest of her life, including in the besieged city of Leningrad in 1942, and signed them “K.H." or “Teacher M.” The voice she referred to as “Teacher" seeped into the verbal reality of the besieged city, interrupting the linguistic dystrophy provoked by the blockade. Most of Obnorskaya's writings were destroyed during the searches of her home at the time of her arrest in the mid-1950s.Olga Obnorskaya lived in a theosophist settlement in the village of Guarek. After the destruction of the post-revolutionary period, the Caucasus region played an important role in preserving a wide range of spiritual movements. The Tolstoyan agricultural communes, theosophist collectives, anthroposophist and anarcho-mysticist groups that settled in the region largely consisted of intellectuals who had given up their careers and life in the city to work the land and try to attain the ideals of harmonious communal living through spiritual growth and physical development. Although they were driven by very different ideas, these groups influenced each other, exchanging views and practical experience. What was the result their experiment? Was it a truly common experience? What obstacles did they find in their way? In the 1930s, over 40 people were accused of promoting a boycott of the Soviet way of life, as part of the so-called Sochi case. As a result, the story of a common undertaking broke into a number of personal histories.

This volume includes previously unpublished photographs from a number of personal archives in St. Petersburg and Moscow, as well as excerpts from Olga Obnorskaya’s writings and artist’s reconstructions. It was compiled with the assistance of Andrei Gnezdilov, Elena Shestopalova, and the Moscow Theosophical Society.

2.

Before leaving Petrograd for Central Asia, and onward to India, the Roerich family left almost all of their possessions with their friends, the Mitusovs. The weathered silk rose that Helena Roerich had previously worn on her dress became a witness-object, one of the few things in Lyudmila Mitusova’s house that survived the Siege of Leningrad. The life of such objects during the siege conformed to the logic of reduction of “excess:” they were objects of exchange, whose value was determined by the need to survive. The objects discussed in this volume were not converted into currency. Hard to sell or use as fuel for the stove, they existed outside the blockade economy. What were they? And what might they become?

Literary critic and blockade survivor Lidiya Ginzburg recalled: “Our daily routes pass houses that have been destroyed during the bombardments, each in a different way. Some of these ruins bring Meyerhold’s theatrical structures to mind." Such shifts of focus, allowing people an aesthetic experience of the unimaginable, horrifying side of objects, are often produced by extraordinary events. In this case, the event was the war, which ruptured peaceful life and broke the usual connections between objects and their meanings. As everyday rituals changed, so did the shape of objects, the properties encrusted in their surface.

The thick woolen blanket that once “burned with fire that did not consume” in a Mongolian desert enters into a tense inverse relationship with the blockade mode of life, with its primitive fire pits inside furnished apartments.

This volume features barite paper photographs of Helena Roerich’s silk rose from Lyudmila Mitusova’s house, which is now the Roerich Family Museum and Institute, as well as photographs of a table mirror and a woolen travel blanket. It also contains excerpts from Helena Roerich’s letters and photographs of her in Kullu, India, in 1942, wearing a similar silk flower.

3.

The drawing of a black sky crossed by spotlights and the white triangle of a boat’s sail in the foreground was made by Misha Mironov (1926—1941 ?) in 1936, and is titled Future Moscow.

The fragment of a figure caught in the spotlight to the right belongs to the famous phantom image of Lenin atop the Palace of the Soviets, a grandiose project which was never built. The drawing would have been nothing more than an example of propaganda imagery reworked by the unconscious, had it not been for a strange turn in the artist’s life that made the image an eerie premonition. Left alone in besieged Leningrad in 1941, Misha recklessly decided to walk to Moscow in order to travel onward to Inta to find his mother, who had been arrested, or to Central Asia to reunite with his sister, who had been evacuated. Captured by German soldiers and later detained by the Red Army, he eventually made it to Moscow and then went missing, leaving behind only words and drawings.

This volume features a copy of the 1941 drawing Future Moscow and Misha Mironov’s letter of October 5, 1941.

4.

The fourth volume opens with a Masonic watercolour dating to the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century. It is from the collection of the State Hermitage Museum, where it is catalogued as “A drawing of Masonic symbols, Russia (?), late 18th—early 19th century, watercolor, ink.” We know that it was acquired in 1941, but its provenance remains unknown. Art historian Galina Printseva describes the drawing as follows: “A sheet of paper, folded in half, featuring an image of a symbolic painting of a cave, where a beheaded man sits at a table on which there are Masonic objects. Above him is a burning forest, to his left, a steep waterfall. A black frame is painted around it. The inscription on the first page reads ‘Tableaus’ Above the scene in the cave is the word “Vengeance.” Just like contemporary art with its catastrophic sensibility, the drawing gives a sense of trying to solve an impossible riddle.

This volume features a copy of the Masonic drawing provided by the State Hermitage Museum and related documents discovered in the course of the research.

Two volumes remain closed to the public at this stage of the project.