Garage Curator Valentin Dyakonov on Congo Art Works: Popular Painting

This summer Garage examines the phenomenon of popular art in two very different places, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Chukotka. Garage curator Valentin Diaconov describes how the exhibition came about.

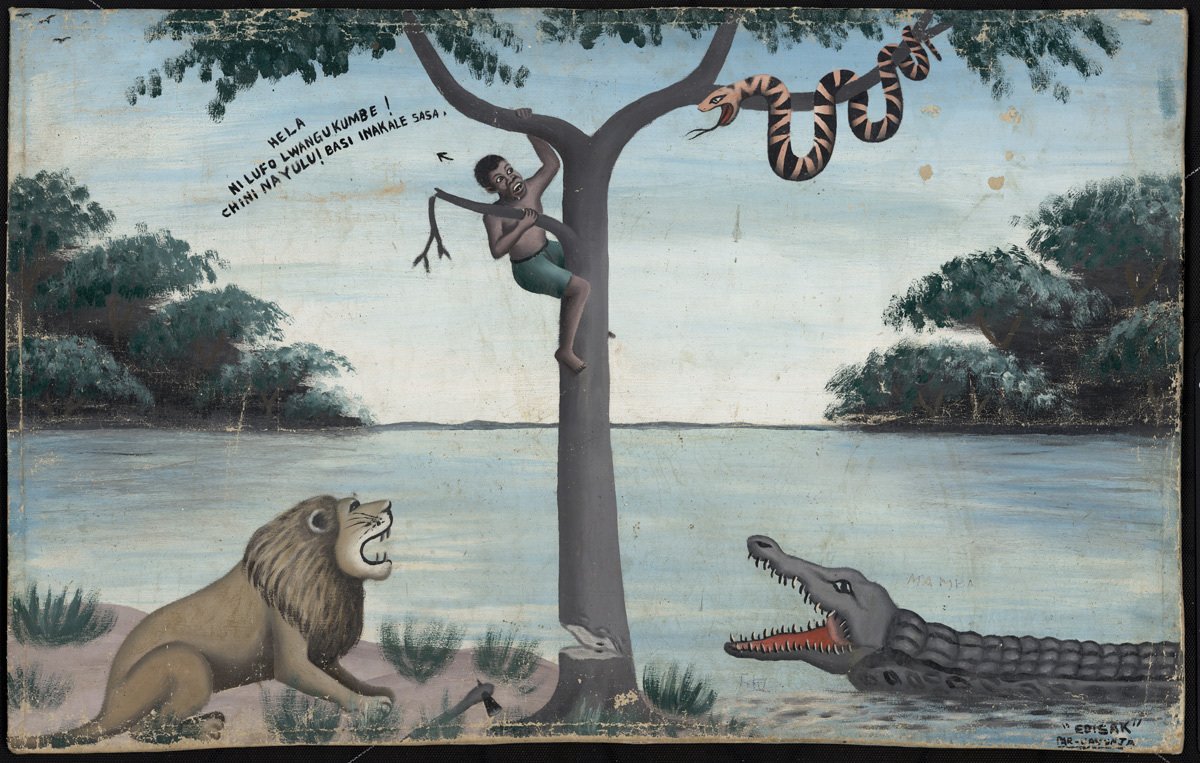

Life is tough on the little man. Climb a tree for a leaf—he meets a poisonous snake. The lion haunts him on the ground, and the crocodile lies in wait in the water. Congolese inakale are traditional proverbs in the form of drawings or paintings. The term can be translated as “tough luck”—something that the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has seen a lot of in the twentieth century.

Edisak

Inakale. Bunia, Ituri, DRC, 1992

Oil on canvas

Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren

First, Congolese workers were exploited by Belgian colonial officials focused on the production of rubber. Towards the middle of the century, after decades of discrimination and racism, Belgium slightly relaxed the regime. Independence was proclaimed in 1960, but was soon followed by the murder of the first Prime Minister of the DRC Patrice Lumumba and the drift towards totalitarianism under Joseph-Désiré Mobutu. The overthrow of Mobutu in 1996 sparked a civil war. Congolese popular painting, which developed as these events were unfolding, was first noticed by ethnographers working in the country. One of them, Africanist Bogumil Jewsiewicki, gathered a collection of 2,000 popular paintings dating back as far as the late 1960s and transferred it to the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA) in Brussels in 2013. Jewsiewicki’s collection served as the starting point for the exhibition Congo Art Works: Popular Painting, created by Congolese artist Sammy Baloji and anthropologist Bambi Ceuppens. Looking for authentic art that meant something for the people of the DRC, and was not merely exotic souvenirs for European collectors, they focused on examples of free creative expression in works produced before and after independence, reaffirming the right of Congolese people to be modern.

Chukotka Carvings

Although Russia is hardly ever referred to as a colonial empire, its history is awash with annexations. The Russian anthropologist Vladimir Bogoraz-Tan (1865–1936) compared the Cossacks who fought in Siberia on behalf of the Russian crown to the Spanish conquistadors in Mexico. The colonization of new territories did not stop after the Revolution: Chukotka became Russian in the 1920s, and in the 1930s the Soviet State launched a major campaign against the American presence in the region, which included forced industrialization, collectivization, and political repression. Chukotka’s earliest walrus ivory carvings were made as souvenirs for Russian and American sailors.

Courtesy of The Sergiev Posad State History and Art Museum-Reserve

Carvings produced during the Soviet era reflected the ideology brought in from Moscow. A common motifs of that time is the juxtaposition of old and new Chukotka: one side of the tusk shows the great achievements of civilization, for which the people of Chukotka should thank the new regime, while the other depicts traditional rites, which had lost their meaning in the world of apartments, collective farms, and airplanes. This appendix to the exhibition of Congolese popular painting shows how folk art from Chukotka evolved into a form that rarely reflected the everyday life of the local population. The Russian version of “popular art” is quite different to the Congolese. This exhibition was prepared in collaboration with four Russian museums: the Sergiev Posad State History and Art Museum and Reserve, the State Museum of Oriental Art, the State Historical Museum, and the Museum of Applied and Folk Art.

Valentin Diaconov, Garage curator

The material was first published in Garage Gazette 2017 issue.