Garage Assistant Curator Ekaterina Lazareva in conversation with Stephen Coates

Garage Assistant Curator Ekaterina Lazareva speaks to Stephen Coates from the X-RAY AUDIO project about the exhibition Bone Music at Garage.

Ekaterina Lazareva: How was the X-RAY AUDIO project initiated and developed?

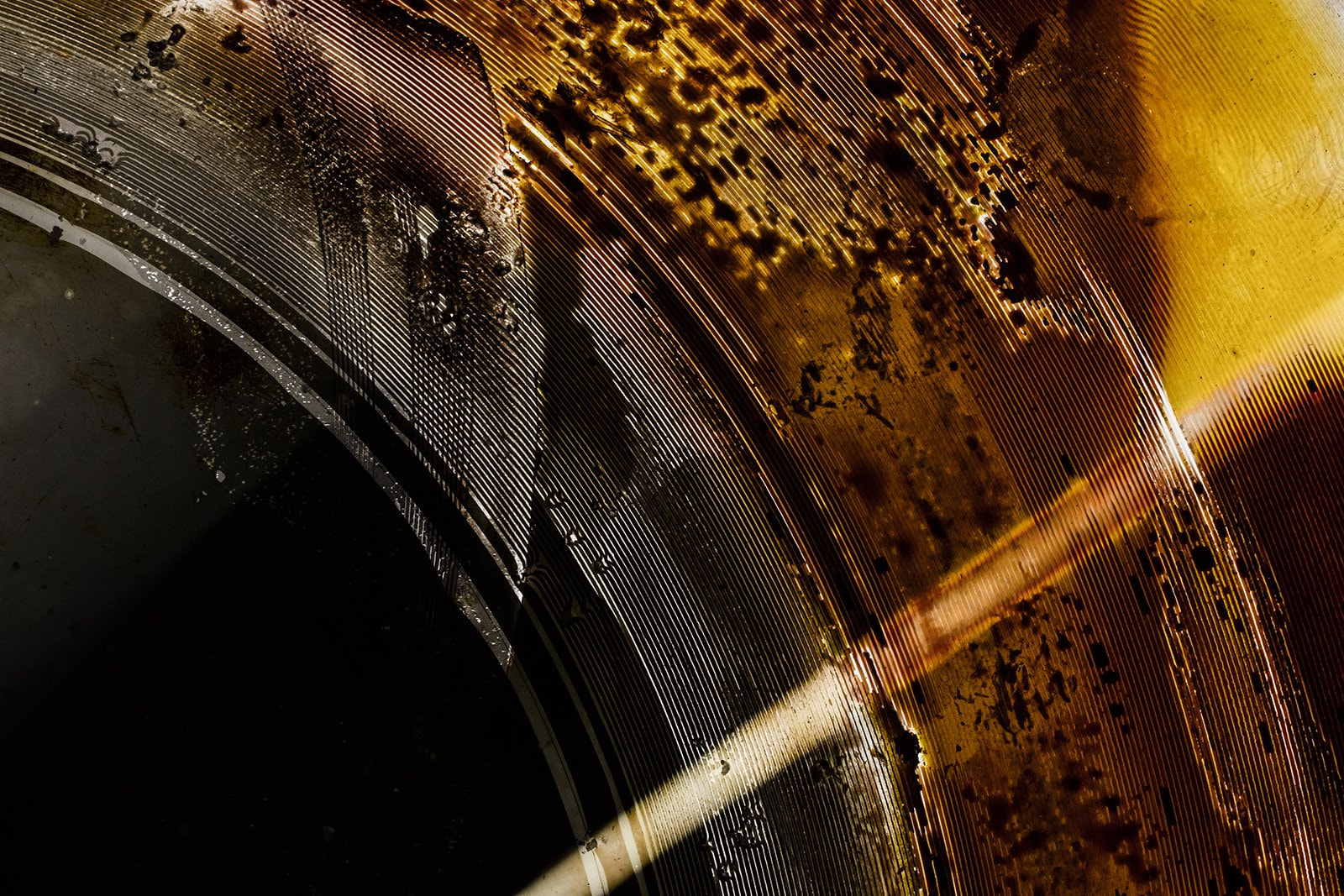

Stephen Coates: It began in 2012, when I was performing in St. Petersburg. During a visit to a flea market I found a strange object that seemed to be both an x-ray and a record. I thought it was ghostly and beautiful. I decided to try to find out its story and eventually that led me to meet an old Russian man called Rudy Fuchs. Rudy was one of the people who made these records in St. Petersburg in the 1950s. After more research and finding more records and meeting more people, we decided to make an archive of images and sounds from the records. And then we made a small exhibition in London with a live event where I told the story of the records and the people who made them as I understood it. The exhibition has now been held twice in London, in Birmingham, Newcastle, in Northern Ireland and in Trieste in Italy. And we made live events in Krakow, Copenhagen, Berlin, New York, and several other places.

EL: Will the exhibition at Garage present something new?

SC: Actually, it is mostly new. We are showing new examples of discs and new films and interviews. And at Garage we have brought the accidental secret aesthetic of the records to the surface. These things that were originally forbidden, a part of street-culture, and disposable objects will be presented as beautiful, high-culture artefacts. We’re also planning live events, including a musical performance, a round table discussion, and film screenings.

EL: As a musician, do you feel nostalgia for a time when music was so important?

SC: One song might have felt very valuable as you would have to work hard to find it. And the fact that some of this music was ideologically forbidden also made it more precious. Today, we live in a time when music is completely abundant, generally nothing is censored, you can get anything anytime you want it—and for no money if you don’t want to pay. That is very different to the time and culture in which these records were made. Perhaps the value of one song now can never be as high as it was in 1949 in Leningrad. I think for all of us this is a question worth thinking about: what is music worth now and what would I lose if it was taken away?

EL: Do you think that forbidden music was a Cold War weapon of subversion that somehow led to the fall of the Soviet Union?

SC: I don’t know how great an effect music had in bringing about change, but it played an important part. When you talk to people from that era and from the time of perestroika, they say how much music mattered to them and how cultural restrictions made them angry and passionate about change. This story is not only about the Cold War and censorship, it is also a story about human ingenuity and creativity, and about people being prepared to risk punishment for the sake of something they love. That’s a lot of things combined in a piece of plastic!