A spotlight on russian art

An extract from “Sotheby’s Auction. Russian Avant-Garde and Soviet Contemporary Art”, Chapter 2 in Exhibit Russia: The New International Decade. 1986–1996, published by Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in 2015, memories of Simon de Pury, one of the main organizers and the auctioneer of the Moscow event in 1988.

I was the curator of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection in Lugano, Switzerland, from 1979 to 1986, and it was through this role that I first went to the Soviet Union. Vladimir Semenov, the Soviet ambassador in West Germany, approached us to present the Collection in Moscow and Leningrad, which eventually led to four exhibitions. Between 1982 and 1986, I was constantly traveling back and forth for these projects, so I got to know many of the museum directors—Madame Antonova at the Pushkin, Piotrovsky’s father[1] at the Hermitage—and also the Minister of Culture.

When I started at Sotheby’s in 1986 I was still advising Baron Thyssen one day a week and had occasion to accompany him on a trip, again to Moscow. In those days, the hotel would always keep your passport until you were leaving, and when we arrived at the airport I realized I’d forgotten to collect it from reception: there was no choice other than to return to the city. An official from the Ministry of Culture accompanied me back to the hotel and then to the airport again, so I spent a decent amount of time with him. At one stage, I casually enquired if he thought there would be a chance that Sotheby’s could organize an auction in Moscow. I was expecting him to laugh, but to my great surprise he was open to the idea and asked which artists I thought should be included, to which I responded that there should be partly pioneers of Russian art and partly unofficial artists, such as Ilya Kabakov, Erik Bulatov, and Oleg Vassiliev. He said he thought it was an interesting idea and remarked that my choice of artists was very similar to those Mr. Jolles liked.

Paul Jolles (1919–2000) used to be the Secretary of State for Commerce in the Swiss government and then the worldwide chairman of Nestlé. Wherever he went, he would spend his spare time in the evenings visiting artists. In Moscow I often accompanied him. I was fascinated. They didn’t have support, barely any materials, or studios. They had no right to exhibit and no chance to travel, but there was a great solidarity and camaraderie between all of them. Later, when the official said that the Ministry would agree to work with these artists, I had to do something that was nearly as difficult, which was to convince people at Sotheby’s that there was a point in organizing an auction in Moscow at that time.

I spoke with Lord Gowrie,2 and then to Michael Ainslie, who was the CEO of Sotheby’s worldwide. These were the early days of perestroika and things were opening up, so there was a huge interest in what was happening after years of the Cold War, of witnessing the changes. I was happy that Sotheby’s eventually decided that they would go ahead with the sale, which then meant several trips to select the works for auction.

We worked mainly with two people from the Ministry of Culture, Sergei Popov and Pavel Khoroshilov. We put together a list, and they got works from the artists, assembling them in a church in Moscow. We selected from this group and also made studio visits with people like Vladimir Nemukhin and Vladimir Yankilevsky, Dmitry Krasnopevtsev, and Vadim Zakharov, who was the youngest artist in the auction.

My motivation was to show to the world what was going on behind the Iron Curtain, because most of the artists were working in total isolation—let’s not forget that this was pre-Internet. I felt an auction would be a great way of putting a spotlight on what was happening and increasing an appreciation of Russian art. Of course, I also worried that after having obtained the works, we had to sell them. It was clear that at that time there were no Russian collectors who would be candidates, so we organized a trip to Mos - cow for collectors from America and Europe, so they could see artists’ studios for them - selves and find out more about their work. This was about one week long. Peter Batkin, who was a sales clerk at Sotheby’s at the time, was in charge of organizing the tour. He did a fantastic job, really thinking outside the box and making everything function behind the scenes.

There were many funny stories from this trip. One American collector, who visited the studio of Igor and Svetlana Kopystiansky, was offered a painting in exchange for his Nikon camera, which he refused. Two days later, during the auction, this work and another by Svetlana fetched huge prices. It was Elton John who bought them. The collector was so upset!

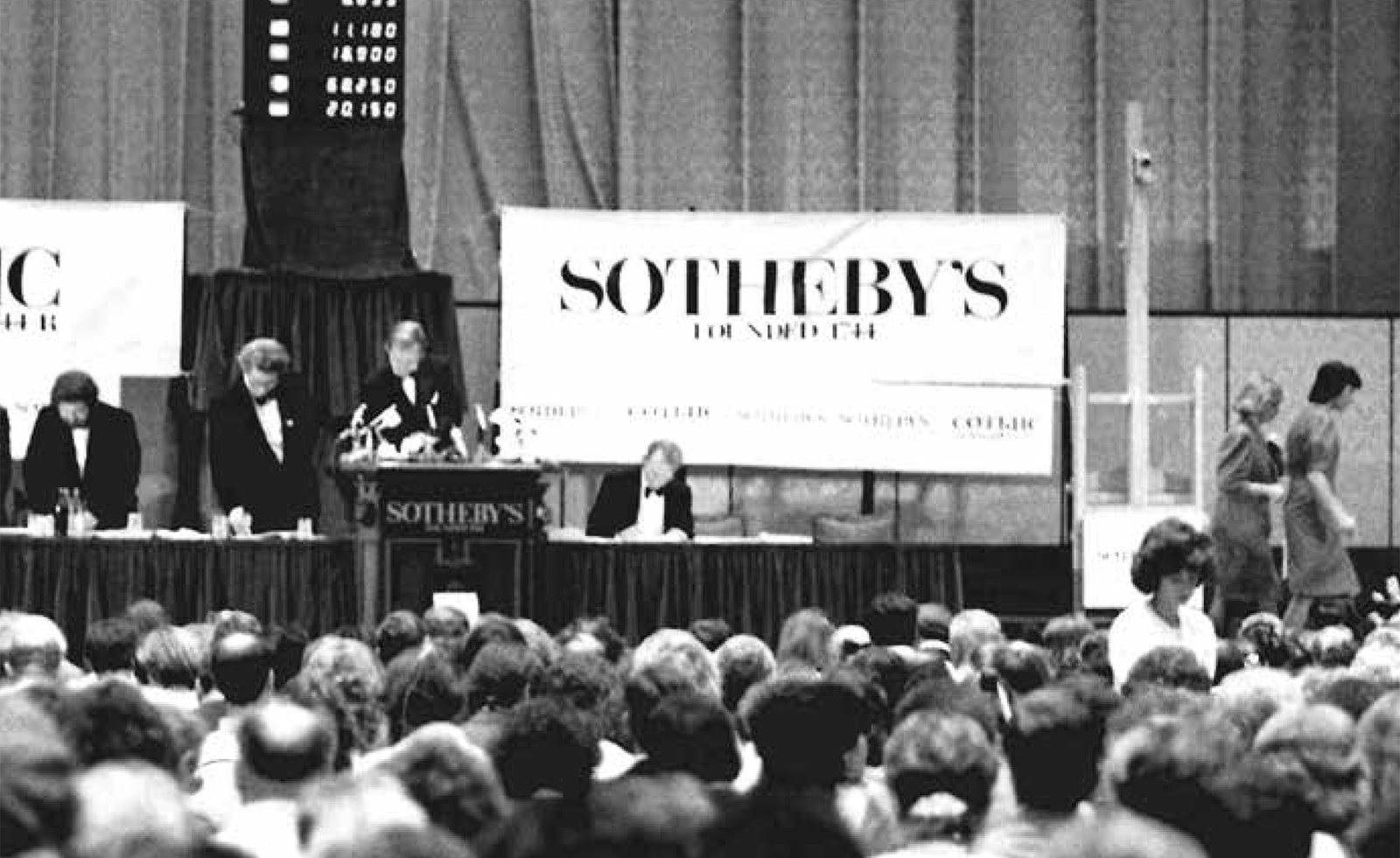

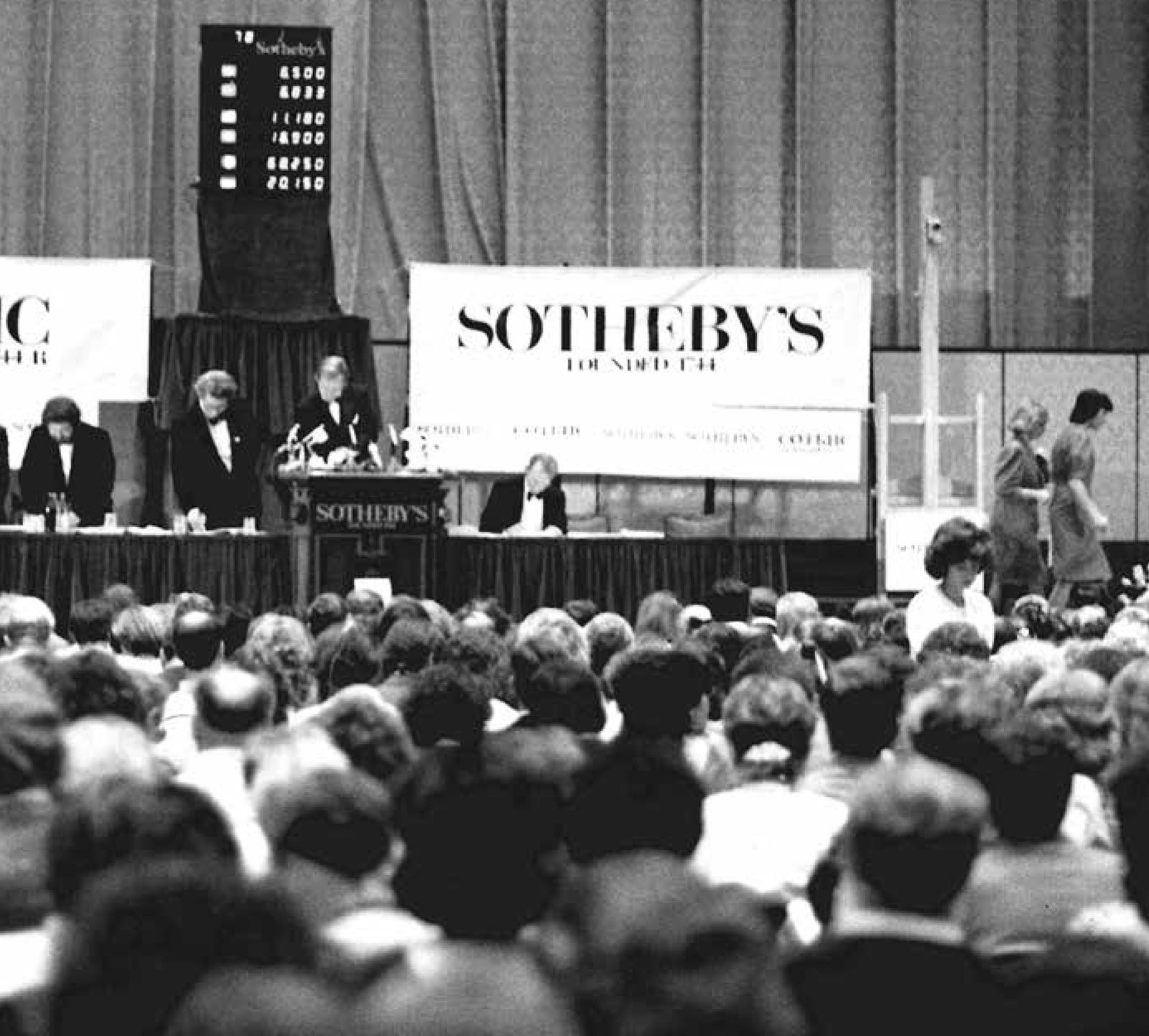

Day of sale, July 7, 1988, Sovincentr, Moscow

Day of sale, July 7, 1988, Sovincentr, Moscow

© Sotheby’s

The auction took place at Sovincentr in the Mezhdunarodnaya Hotel. TV stations came from all over Europe, and the auction room was packed. There were tensions up to the last minute, such as rumors that a member of the Politburo who was an adversary of Gor - bachev was exerting pressure for the whole thing to be canceled —even after all the collec - tors had flown in —but luckily nothing material - ized from that. The other total nightmare was that we needed people to be on the telephone during the auction but none were working on the day. We had this whole phone bank with my colleagues at the ready, but five minutes before the auction they were dead. That’s the only time I was really nervous, because the top management of Sotheby’s were all there, including Alfred Taubman, the owner. I thought, “OK, well, this is it.”

At that stage, Batkin saw that I was in a bad state and gave me a glass of vodka, which I took in one gulp and went out to the podium to start the auction. Then a total miracle happened. I suddenly saw all my colleagues eagerly dialing: the phone lines had started working. And so it began.

The first cycle was the Russian avant-garde, followed by the unofficial artists. The first lot went off like a bomb. People were bidding like crazy, and it reached three, four, five times more than we had expected. After every fall of the hammer the entire audience was applauding fanatically. It was like being at a football match each time a goal is scored. When it came to the unofficial artists, it was unbelievable, particularly with the record for Grisha Bruskin’s painting, which was much more than we could have ever expected in our wildest dreams. It was funny, because after the auction he was in a state of shock, and he dropped his glasses, which broke on the floor. As he was worriedly trying to pick up the pieces, his wife said, “Don’t worry Grisha, you are a rich man now. I will get you new glasses,” but he didn’t seem to believe it was possible.

I think the auction was a pivotal moment because everybody who witnessed it saw the prices that these artists’ works could command, even when they were the so-called outcasts of society. The event was not without its contentious moments, however, even from the artists. The night of the auction, they did a parody of the whole thing, creating an impromptu performance: imitating me taking bids, imitating the crowd, and making com - ments about the absurdity that this art was suddenly worth money when it was worth nothing before. Nonetheless, the realization on the part of the Soviet officials that all these foreign collectors were paying such big prices for the works meant the beginning of the end of the Artists Union and the whole system that divided the opportunities for official and unofficial artists.

The most problematic issue that arose after the event was to do with payments. The agreement was that as soon as Sotheby’s received funds from the purchasers they gave money to the Ministry, which was supposed to pay the artists. But week after week went by, and we would hear the artists had not been paid. The Ministry kept saying it was in pro - cess, but gradually the press started enquir - ing, and what had been a PR triumph risked turning into a PR nightmare. That’s where Lord Gowrie played a very important role as Minister for the Arts in Thatcher’s government: Mr. Gorbachev was coming to England on an official state visit, and Gowrie was able to get the problem onto the agenda. The day before Gorbachev was to leave for London, suddenly all the artists got paid.

Excerpted from an interview with Kate Fowle, April 8, 2015.

Simon de Pury Chairman, Sotheby’s Switzerland and later Sotheby’s Europe (1986–1997).

[1] Mikhail Piotrovsky has been director of the State Hermitage Museum since 1992. His father, Boris Piotrovsky (1908–1990), was director of the Hermitage from 1964 to 1990.