Sekretiki No. 28. The Question of a Nature Retreat

By 1964, the artist Oskar Rabin had saved enough money to move to a cooperative apartment in Chertanovo and move his family from the legendary barrack in Lianozovo that had been an important public platform for the underground art of the Thaw era.

Together with his wife, Valentina Kropivnitskaya, and their children, Rabin moved to the concrete jungle, immediately raising the need for a natural “retreat.” Through Vladimir Nemukhin, an artist closely linked to the Lianozovo group, they found one on the Oka River. It was a dacha in the village of Priluki, where likeminded artists such as Dmitri Plavinsky, Lydia Masterkova, Nikolai Vechtomov, and Boris Sveshnikov also rented homes. Nemukhin called Priluki, where everyone spent the summer, “the Barbizon of unofficial art.”

Ten years later, Andrei Sakharov was commissioned by the New York magazine Saturday Review to write a futurological forecast. Entitled “Tomorrow: The View from Red Square” (published in Russian in 1988), it envisaged the emergence of the Internet (or UIS, the Universal Information System) and the splitting of the planet into two territories. “The PT [Preserve Territory], larger in area, will be set aside for maintaining the Earth’s ecological balance, for leisure activities, and for man to actively re-establish his own natural balance.” In other words, it will be a huge “retreat,” while the “Working Territory” will be marked by high population density and urbanization.

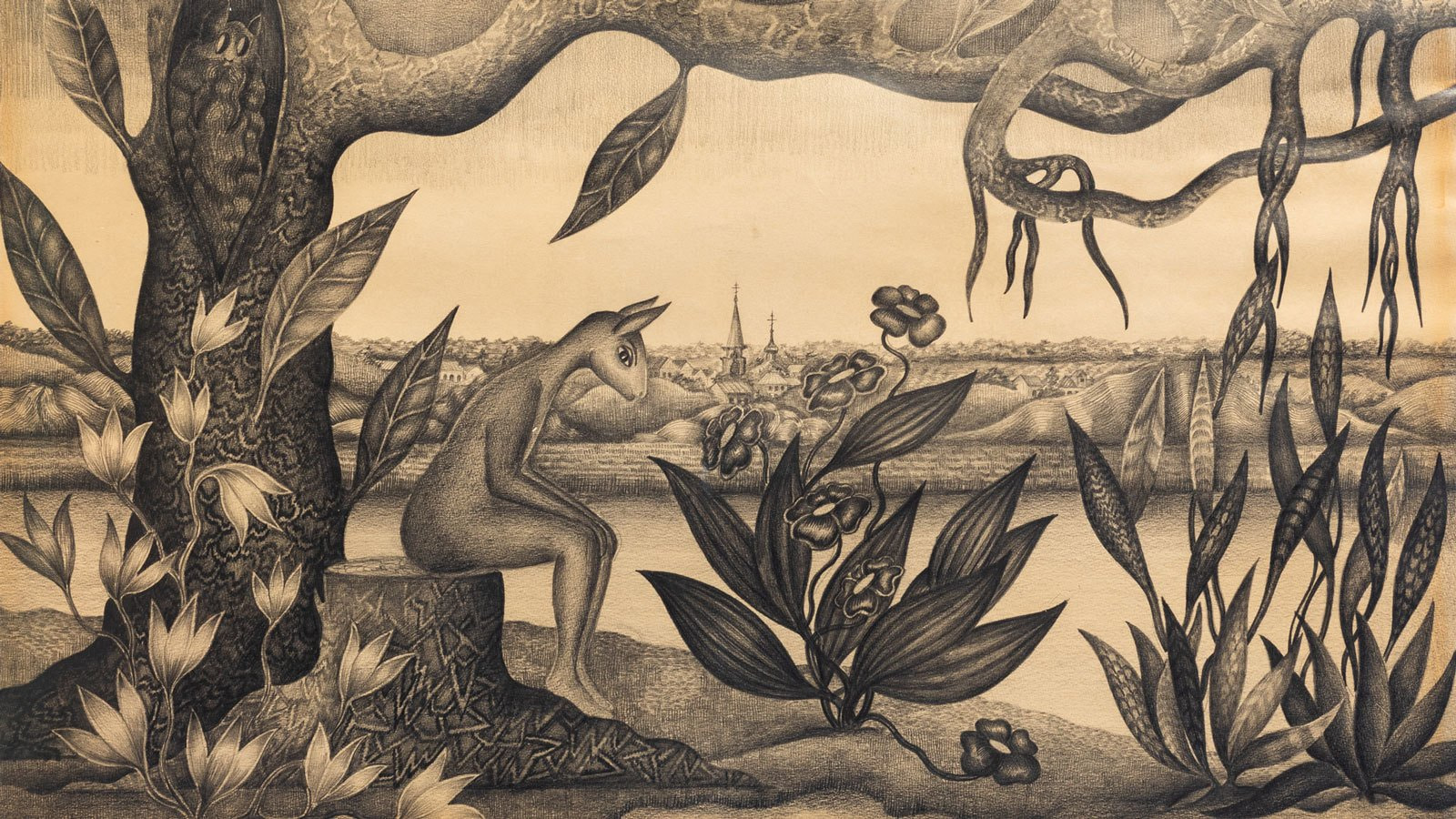

Valentina Kropivnitskaya

Log. 1977

Private collection

Valentina Kropivnitskaya’s drawings look like a report from the utopian thickets of the Preserve Territory. There are two different versions regarding the kind of creatures which inhabit it. Since Sakharov warned humanity about the nuclear threat, might these mutants have been brought to life by the collision of the two superpowers of the bipolar world? Alternatively,

they might be humans desperately wishing never to return to the “Working Territory.” With masks on their faces, they pretend to be something between human and animal. With an animal head one can stay in the “retreat” forever.

Sakharov spent his $500 fee for the article in a Beriozka store, where Soviet citizens could buy quality imported goods, albeit by a complicated route. Like yoga, abstract art, and the majority of religious affiliations, in the Soviet Union the Beriozka was a sekretik of a sort. The press occasionally wrote about these stores and the system of stripes on Vneshposyltorg checks with which Soviet citizens working or receiving payments from abroad were paid (no stripes was the best option, a blue stripe prohibited access to most products). You couldn’t just walk into the store from the street. Plainclothes police officers at the entrance made sure potential shoppers had currency or checks. As a result, Sakharov—a technocrat and traitor to the motherland according to the Soviet press—was now on the same consumer level as loyal specialists allowed to travel abroad. But instead of spending the money on himself, Sakharov bought food to send to political prisoners in the Mordovan camps (political repression, rather than prosecution for real crimes, was another grim sekretik of the Brezhnev era).