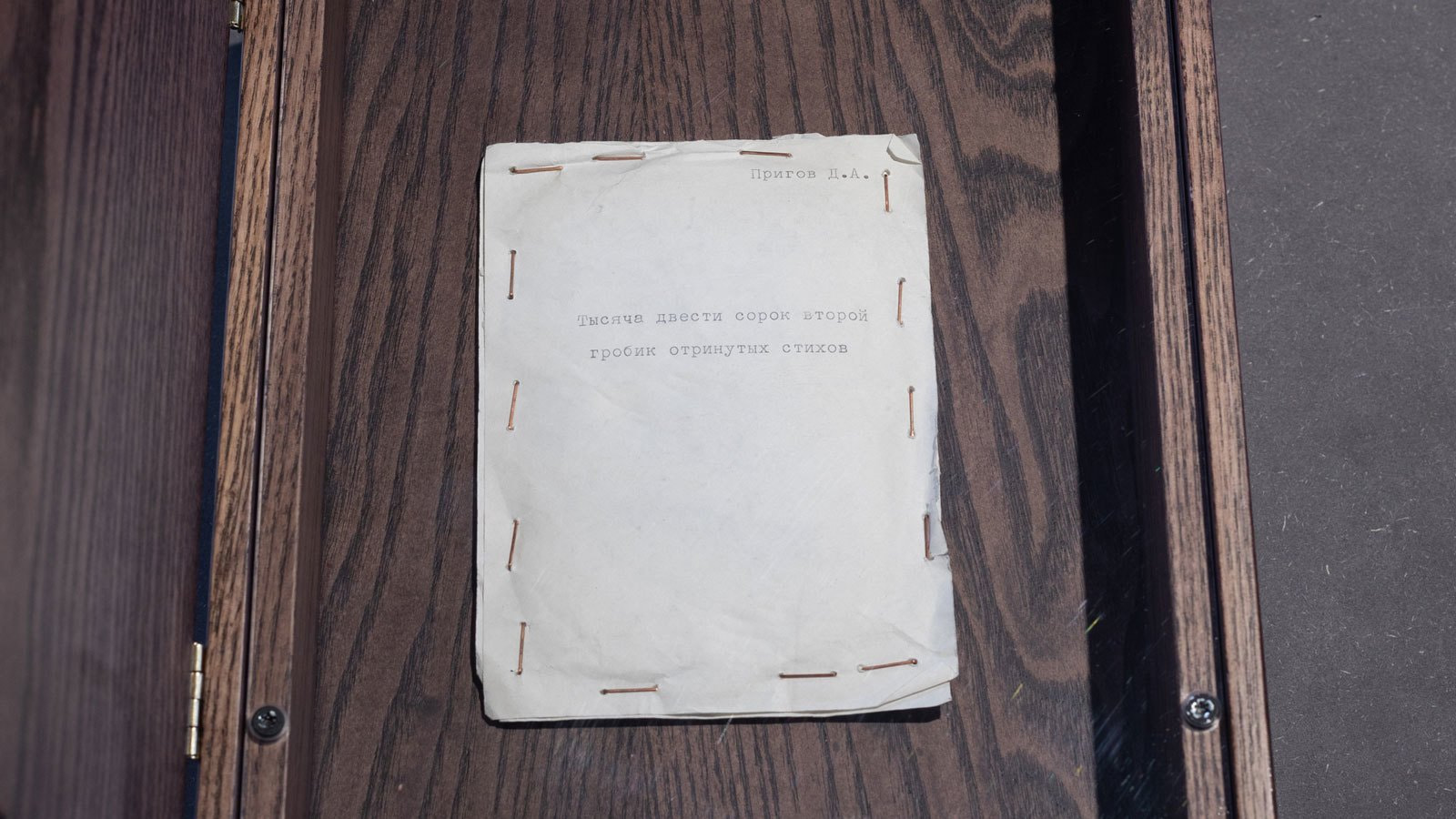

Sekretiki No. 5. Small Coffins of Rejected Verses by Dmitry Prigov

Sekretiki was a popular Soviet childhood game. It was all about strategy, but charged with daydreaming, aesthetic pleasure, and self-learned balance between creatively shaped solitude and mindfully practiced social engagement. First you find a secret place in a forest or a backyard, where you can spend time concealed from the view of others. You dig a hole the size of a fist and store your treasure (an odd pebble, a selection of colorful candy wrappers, a feather, a very personal drawing, a flower). You arrange them in a representative and aesthetically pleasing display, put a piece of glass on top, and camouflage the hole by covering it with moss or soil. Then you choose who you trust to share this secret: your fantasies and tastes, your valuables and values.

The archetypical components of collecting, arranging, hiding, and confiding in the structure of the game are similar to the creative methods employed in Soviet period nonconformist art. Made within the constraints of surveillance and an ideologically controlled social environment, many of these works of art (or the means of their display and distribution) explore the complex relationship between private and public. The human inclination toward secrecy as ritualized forms of keeping a secret or revealing it to selected confidants was turned into an aesthetic game. Its rules often included absurdity, double meanings, cryptographic language, and hide-and-seek tactics.

Some works invited participation, while others were constructed as time capsules with self-destruction encoded in their format to protect against intrusion. One can open the sealed sepulcher of Dmitri Prigov’s rejected poems, but there is no guarantee that the literary find will compensate for the ruined artwork. It is not polite to peep through a keyhole, but who said that art is about politeness or that our aesthetic inclinations are not driven by curiosity regarding the intimate.