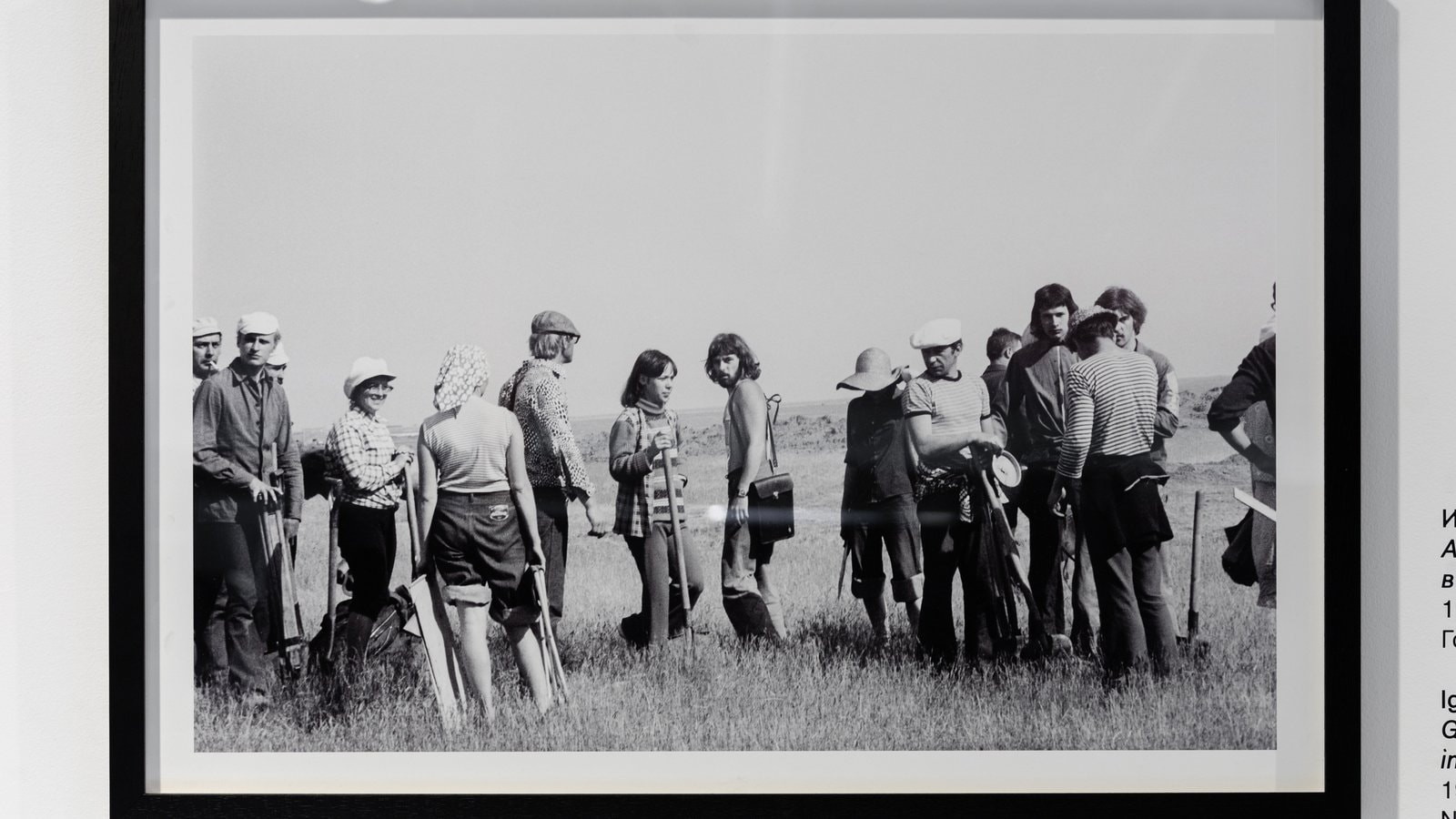

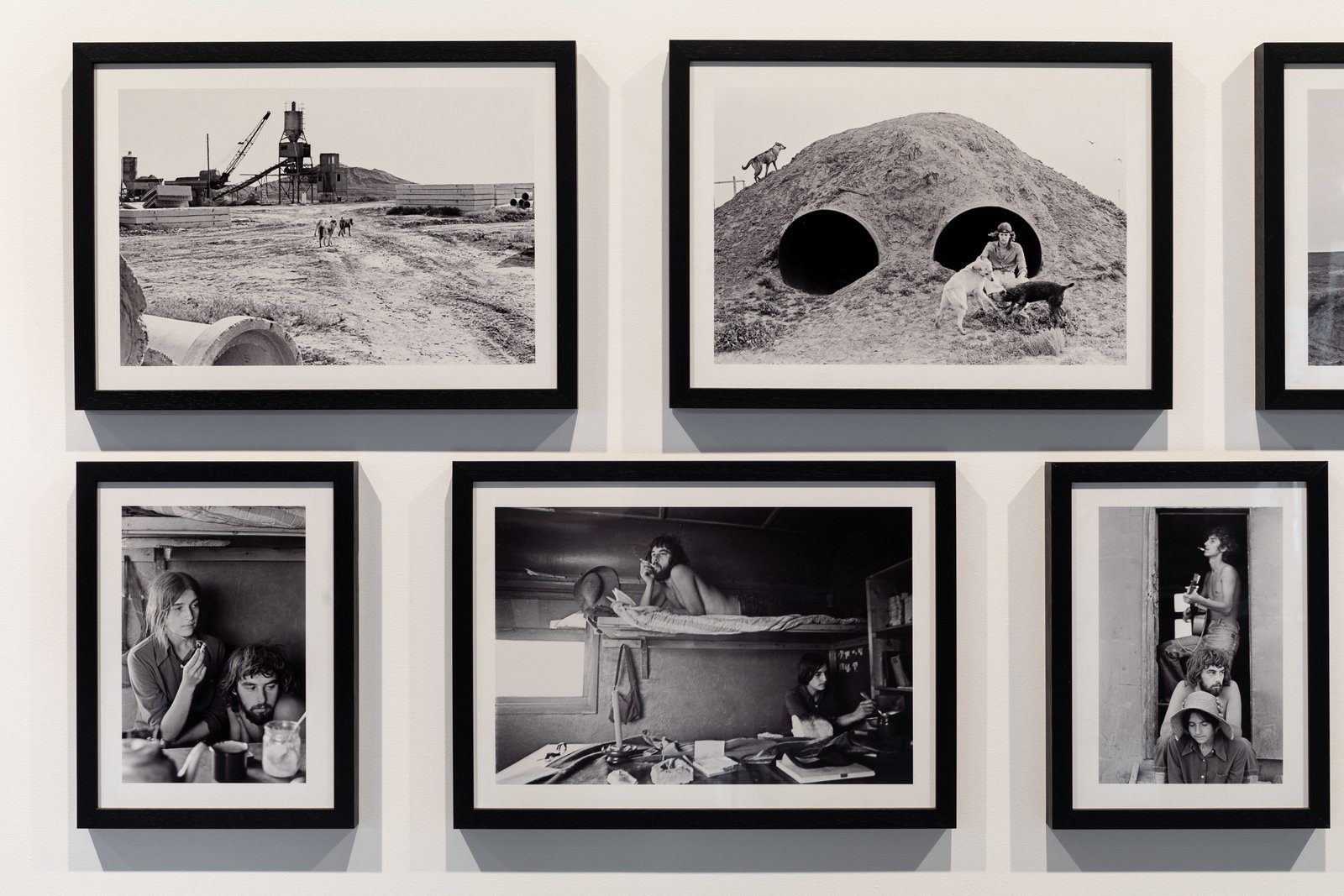

Sekretiki No. 6. Nonconformists at Archeological Digs

Igor Palmin,

From the series The Enchanted Wanderer and The Disquiet, 1977 (printed 2019)

Courtesy of the photographer

In unofficial cultural circles, scientific expeditions organized by universities and institutes were a well- known option for a brief and adventurous escape from the ideologized environment of Soviet everyday life. With informal conversations and guitar-poetry by the campfire in the evenings, and the fact that excavation sites in remote regions were far from the controlling gaze of the authorities, such expeditions attracted those whose declared aim was the avoidance of and non- engagement with anything Soviet.

Palmin’s original idea was to photograph the whole band of exotic countercultural figures who had joined the expedition, but only a few were willing to pose. One of them was the young Moscow hippie Sergei Bolshakov, a drop-out from Moscow Engineering Physics Institute, who had feigned insanity to escape compulsory military service and was closely linked with the Moscow circle of nonconformist artists. The photographer first met him in 1975, when photographing the nonconformist exhibition in the House of Culture at the Exhibition of National Economic Achievements (VDNKh). As a member of the artist group Hair, Sergei was one of those behind the embroidered hippie flag, which was removed from display by the KGB on the day the exhibition opened. The final shot of Palmin’s series, with Sergei departing toward the horizon in the company of stray dogs, recalls the slogan on the confiscated flag: “Country Without Borders.”

A plaster copy of an African ritual mask, sandwiched between a comedian’s bald-head wig and a mass- produced bust of the Red Army Marshal Kliment Voroshilov, is not an obvious or predictable encounter. The mutant creature brought to life by overlapping cultural narratives belongs to the world of Prigov’s storytelling. There are meanings running in all directions, searching in vain for a butterfly effect that could explain their sudden togetherness. The totality of each separate medium or social sign system is undermined by being combined with others.

The sculptural collage of found objects, created as a spoof of Soviet power and revealing its ritualistic and religious nature, is more than mere political critique. Its absurdity contains a mystical horror related to the cultural crises of the globalized world, where to endure doubt is the ultimate human condition and the starting point for a new type of anthropology with which to study our habits and social instincts.