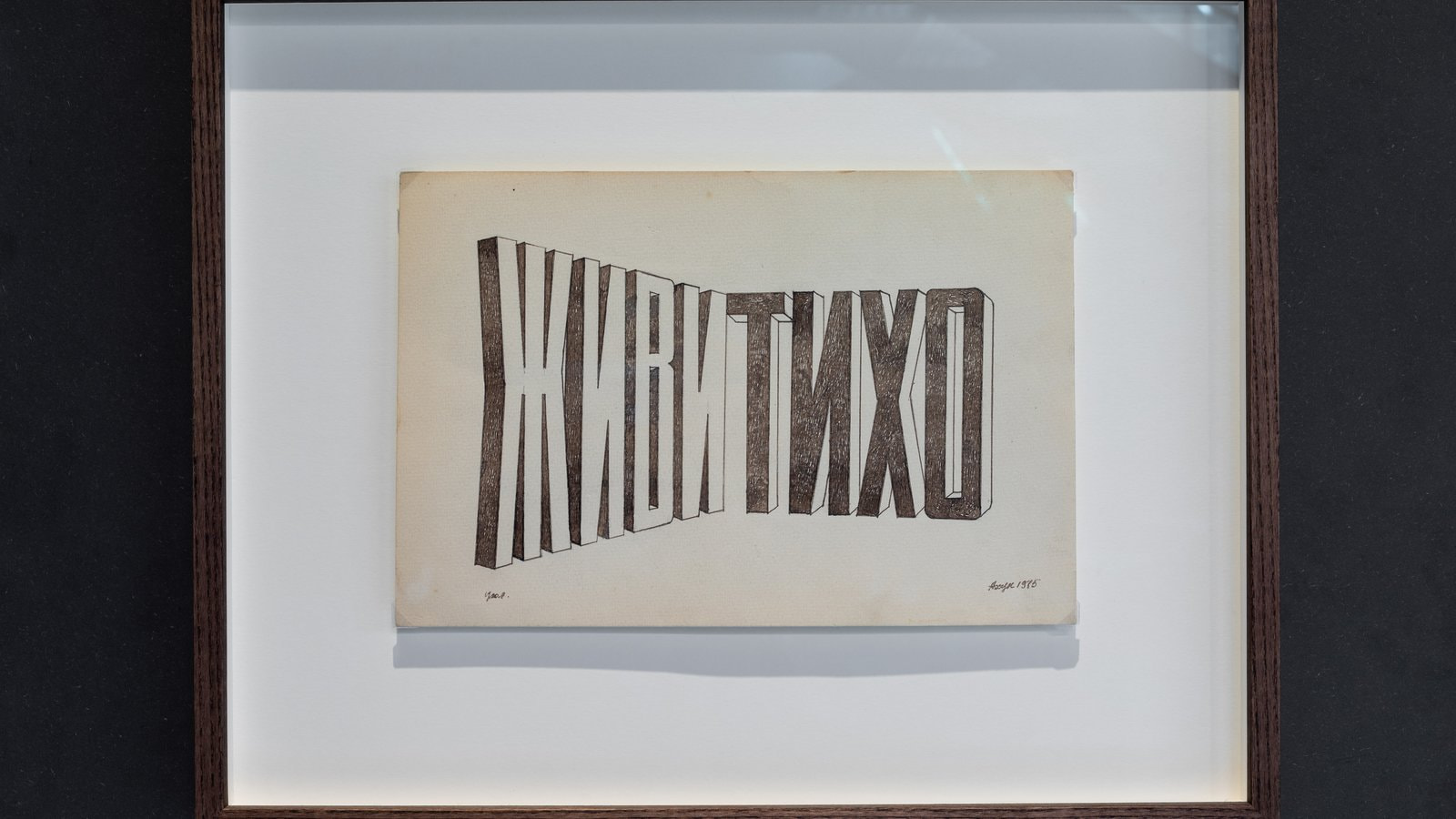

Vyacheslav Akhunov is a major figure in Central Asian art. He uses a diverse range of techniques, and even so his entire body of work is, to varying degrees, a critique of power. The absurdity and abnormality of Soviet life is also reflected in Breathe Quietly and Live Quietly. The artist suggests that the everyday life of the Soviet people, with their desires, dreams, and passions, was held back by ideological directives imposed by the authorities. The norm of living in totalitarian societies is not just about “living quietly” but also about trying to “breathe quietly.” There are two versions of each work: a drawing, as shown here, and an installation which occupies the exhibition space to the ceiling, thus pushing to the limit the metaphor of the presence of ideology and power in private life.

With manic consistency and meticulousness, Vyacheslav Akhunov reproduces and juxtaposes various Soviet memorabilia, from photographs of leaders and members of the Politburo to slogans, documents, song lyrics, flags, and other objects representing communist ceremonial. One of the artist’s most notable projects, which he has worked on much of his life, is the series Mantras of the USSR. For decades, Akhunov has been collecting artefacts, such as newspaper clippings, old folders, archive records, and canvases, and covering them with excerpts from textbooks on scientific communism and dialectical materialism in his compact handwriting. The project consists of thousands of such objects.

Akhunov remembers Patterns as his “first independent work.” Here is his story: “At our institute, after lunch, there were lectures on Marxism-Leninism, scientific communism, art, dialectical materialism, and the history of the Communist Party. And as if we were in the army, they forced us to write notes. Out of laziness, I began to write them on paper patterns, and then I realized that wearing a dress made from these patterns would look very ideological. So I covered the patterns with lectures on Marxism-Leninism.” This work represents a collision of the multiple meanings and cultural realities of the time. Magazines with patterns were especially popular in the Soviet Union, as it was extremely difficult to get good clothes due to the severe shortage of consumer goods. People often sewed garments for themselves. And whereas these magazines are in a sense a symbol of the deficit of goods in the Soviet Union, the uniform “bootleg” recordings on them testify to the amount of time wasted on the endless memorization of “party testaments.”

Famous for their humorous and irreverent actions, in 1982 Mukhomor (Toadstool) group (Konstantin Zvezdochotov, Sven Gundlakh, brothers Vladimir and Sergei Mironenko, and Alexey Kamensky) created instructions for a performance. The artists’ friend, Andrei Degtaryev, was invited to take part. He arrived at Begovaya metro station at the appointed hour and received a train ticket and a map of the area from a stranger. In the country, 30 kilometers away from Moscow, Degtyarev used the map to find a freshly dug hole where there were two boxes with the following instructions: 1) reveal the next sheet only when you have fulfilled the previous instruction; 2) take off all of your clothes; 3) put on the clothes in the boxes; 4) put your clothes in the boxes and bury them; 5) return to Moscow with the train ticket provided. The boxes contained tarpaulin trousers, a padded jacket, and artificial leather boots. Degtaryev was planning to go to a birthday party after the action and was dressed smartly, in a corduroy three-piece suit (which was hard to come by, like any quality clothing). But that didn’t prevent him from carrying out the instructions. Watching with a spy glass from a distance was Nikita Alexeev, invited by the members of Toadstool group. Gundlakh suggested the following interpretation of the performance: “Among other things, we raised the question: How many people are needed for artistic act to take place?” Incidentally, Degtaryev’s clothes were returned to their owner a few days later.