Sekretiki No. 25. Fortune Telling Using the Book of Changes

In October 1964, a Chinese student, wise enough not to mention his name, wrote home from the Moscow State University dormitory. “I learnt two pieces of good news at once: China detonated an atomic bomb and Khrushchev has been removed as General Secretary. This demonstrates that the Western wind has finally died down. The wind from the East is gaining momentum. Genuine Marxist-Leninists are winning.” The student’s optimistic pro-Chinese forecast was cited by the Chairman of the KGB, Vladimir Semichastny, in his regular note on the mood in the country to the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

The student was right: the storm of change in Russia had come to an end, progress slowed to a crawl. In the period from 1966 to 1981, 44% of members of the Central Committee maintained their positions. Brezhnev practiced a bureaucratic version of Taoist inaction using the slogan “Trust in Cadres,” which allowed local party workers to establish family dynasties and develop a Soviet version of feudalism. Its dismantling would begin from the Central Asian border areas, but only after Brezhnev’s death.

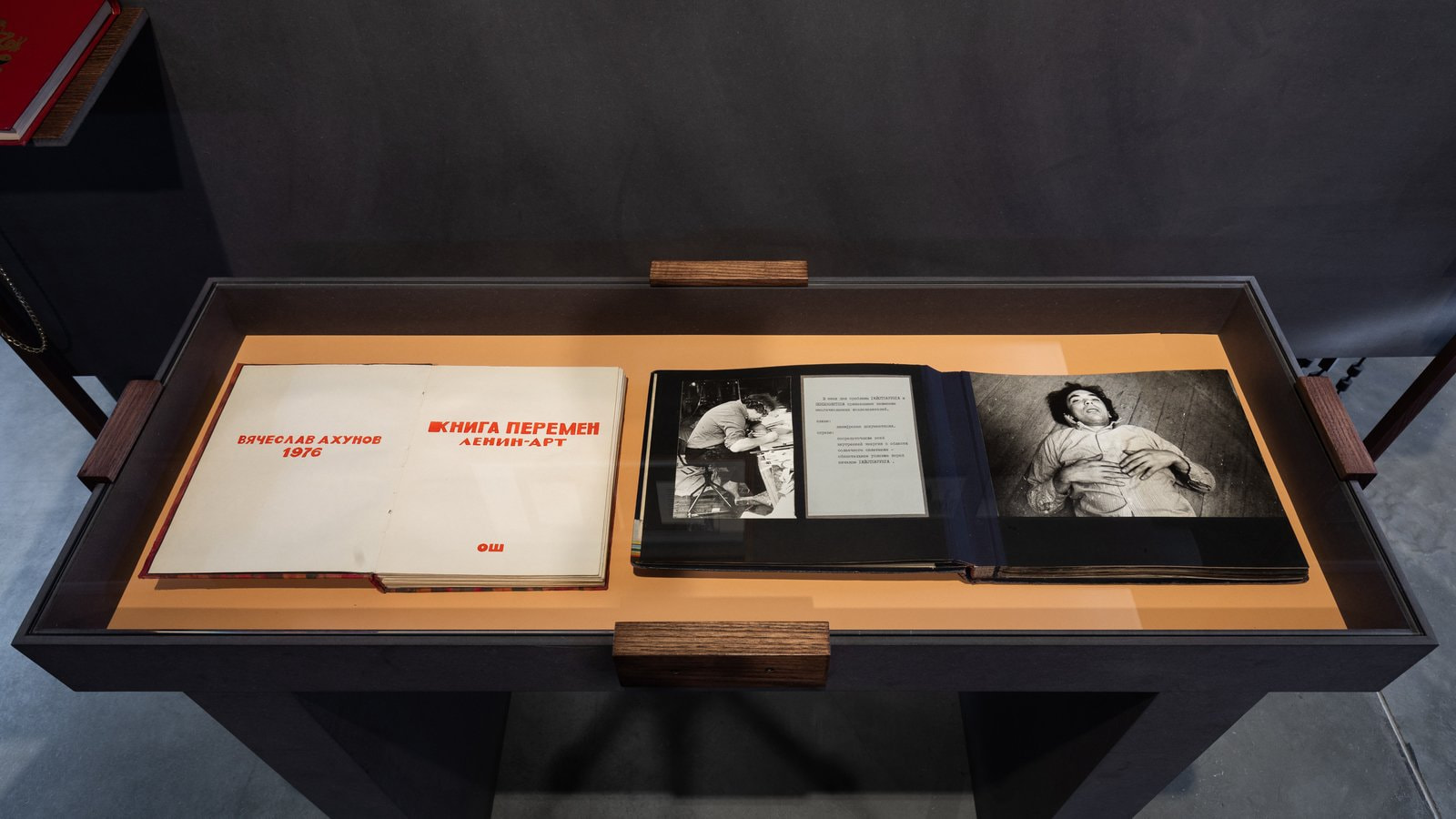

In October 1985, six fishing lines were tied to the rotating pipe of a metal coring collar dug into the earth on the Kievogorskoe Field, with the other ends attached to different trees at the edges of the wood. The action Capstan by the art group Collective Actions was a spatial expansion of the I Ching (The Book of Changes), which contains 64 hexagrams each consisting of six solid or broken lines. Each hexagram has an interpretation. This ancient book of Chinese philosophy had a wide circulation in the narrow circles of Soviet mystics and experimenters. Along with its practical function—fortune-telling—the book also had a symbolic meaning as something opposite to Marxist-Leninist ideology. Drawing on the idea of history’s rational development, the political project of the Soviet regime implied progression toward its grand finale, communism. The mental health of members of the underground was largely dependent on practices of “ritualized uncertainty,” in which the 64 I Ching hexagrams proved very helpful. The Chinese classic even inspired several variations, which used parody to emphasize the original’s value. Examples include the Sots Art Book of Changes by Vyacheslav Akhunov and the carnival version, The Book of Sequels by Igor Makarevich.

After the small group of viewers had received the “score” of the action, its author Nikolai Panitkov began to turn the collar. The weather suddenly worsened. As Andrei Monastyrsky, the founder of the Collective Actions, recalled, “white darkness fell upon us, as if the sky was playing our score.” As soon as the fishing lines began to tear one after another, composing various hexagrams—from Xiao Kuo (“preponderance of the small”) to Kun (“execution”)—the clouds dispersed and the wind stopped. Only the metaphorical wind of change kept pace. Two years later, it brought the long-awaited peace in relations between China and the Soviet Union, with the perestroika announced by Gorbachev finally coming into line with the “policy of transparency and reforms” launched by Deng Xiaoping in 1978.