Sekretiki No. 1. Happenings and Physical Culture in the USSR

The athletic body was a long-established symbol of communist self-discipline, and sport was seen as the ideal tool for achieving mass physical participation in a militarized society. The social context of the 1960s—with a population that had seen conscription decrease under Khrushchev, at the same time as consumer choice in goods and ideas increased—provoked new attempts at propaganda designed to generate a popular sense of militarized patriotism and collective ownership of one’s body as an economic instrument. The national sports programme Ready for Labour and Defence (GTO), initiated by the Communist Youth League (Komsomol) in 1931, underwent significant reforms in 1972 to become a mass movement for all age groups. By 1976, 220 million people had been awarded GTO badges after having passed tests in running, throwing dummy grenades, doing push-ups or just having pretended to enjoy it as a tongue-in- cheek formality organized annually at the workplace.

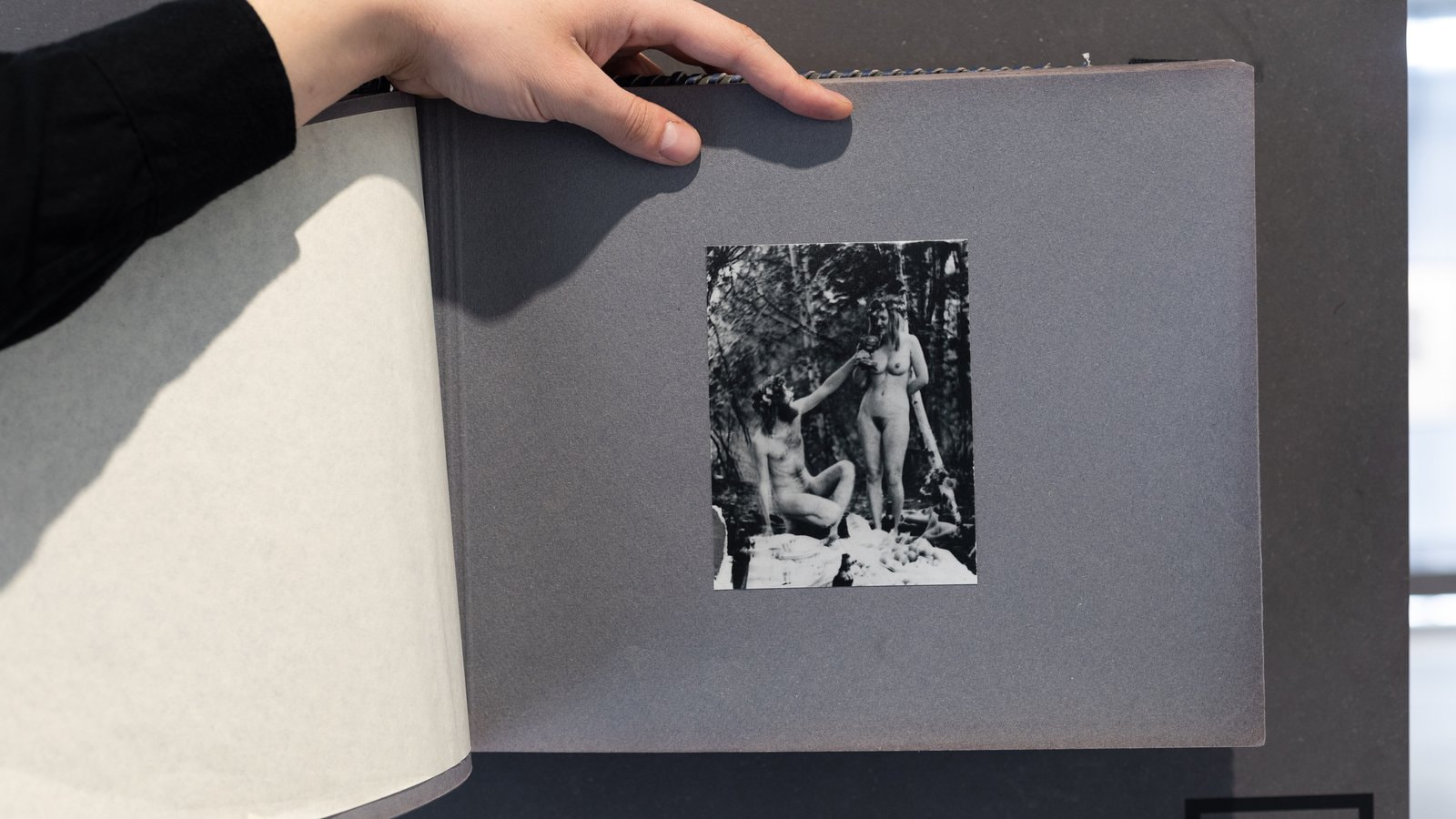

A different understanding of the body and its ownership was cultivated at a number of remote beaches near Riga, practically unpopulated due to the neighboring army base. Favored by nudists since the 1930s, they were a perfect playground for Andris Grīnbergs’ early happenings, in which pagan rites and a martyrdom aesthetic was mixed with Polish theater director Jerzy Grotowski’s ideas about performers and spectators co-creating events as “an act of the most deeply-rooted love between two human beings.”

Grīnbergs’ two-day-long happening Wedding of Jesus Christ (1972) took place shortly after like-minded enthusiasts at the Lithuanian Academy of Art had organized an unauthorized staging of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar, the musical’s unacknowledged European premiere. Many performers were subsequently targeted by the KGB.

The Soviet system discriminated not only against specific individuals but also entire art forms, denying them the status of a professional art. Performance art belonged to these genres and, consequently, existed as a hybrid “in-between” of diverse practices, such as acting, dance, poetry-reading, musical performance, and photography. All of them were present in Grīnbergs’ happenings and provided participants—musicians, photographers, writers, actors—the opportunity to experience the cross-disciplinary approach not only as a new form of creative freedom but also as the liberation the body.