Bambi Ceuppens questions the idea that Congolese popular painting is a colonial genre, arguing that it forms part of a much longer history of inscribing meaning onto surfaces, from rocks, sand, material objects, and bodies to wall paintings.

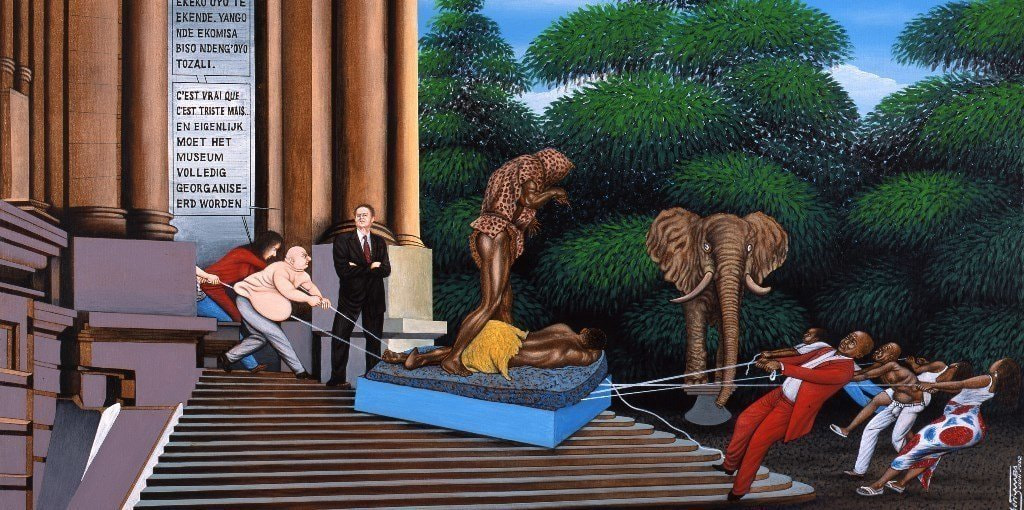

The identification of three-dimensional “ethnographic” masks and statues as “typically” African and two-dimensional popular paintings as “colonial” on the grounds that painting was introduced by Europeans tells us more about the Western appreciation of African masks and statues than about the history of African cultural production. Generally speaking, “real” African three-dimensional objects are identified with figurative representations and “real” African two-dimensional objects are associated with geometric motifs. In reality, many three-dimensional objects contain geometric motifs and figurative designs feature in sand drawings, rock art (which in Congo dates from at least the seventh century), and initiation houses. Historically, Congolese tended to inscribe figurative and geometric meanings onto flat services—such as rocks, sand (drawings), human skin (scarification), masks, statues, gourds—in a religious/ritual context, often linked to rites of passage. Rock art in caves which may have been used for initiation rites was not freely accessible and inscriptions on the inside walls of initiation houses were only accessible to the initiated, but tended to endure. By contrast, sand drawings are wholly ephemeral, and while they may be performed in the public sphere, their meaning may only be understood by the initiated. Contacts with Europeans at the end of the nineteenth century led to inscriptions which served a different purpose, be it for the benefit of local users or for European “customers.” In this context, the distinction between “traditional” and “colonial” inscriptions becomes complicated.

Like sand drawings, popular paintings are not created to last over time or to be transmitted from one generation to the next, but to serve in the context of a performance or another type of communication with human beings. Musician and educator Christopher Small introduced the term “musicking” to counter the idea that people listen to popular music passively and to do justice to the ways in which they engage with it actively through discussion, dancing, etc. Popular painting, like popular music, is both process and product.