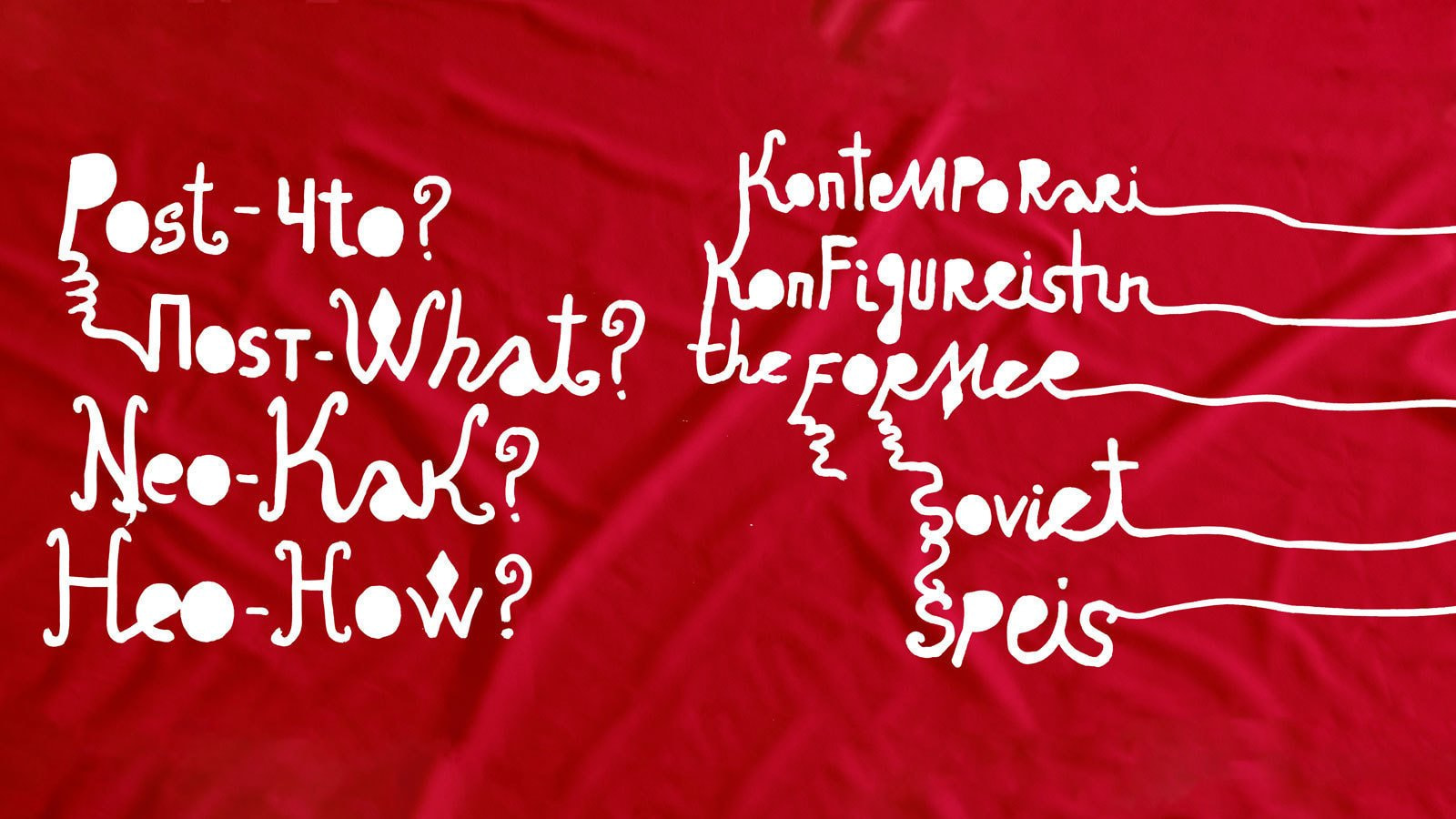

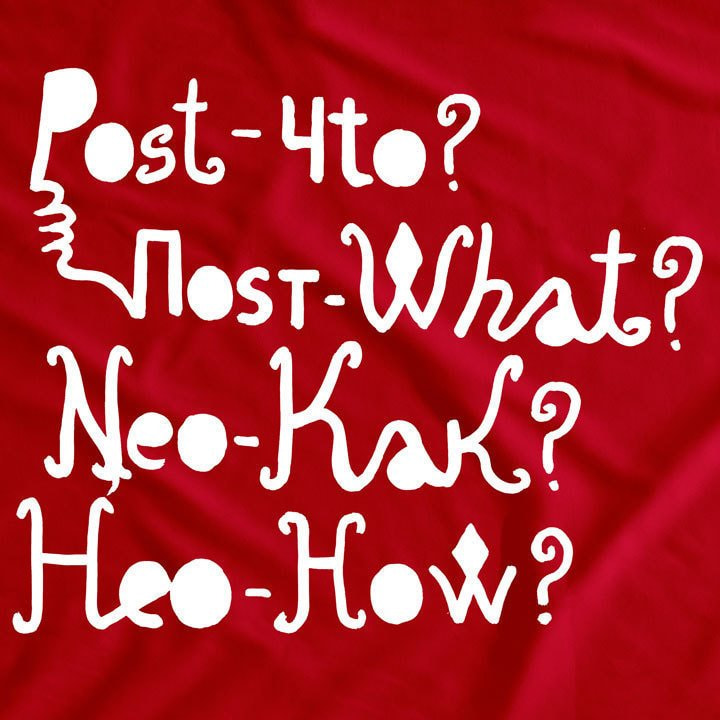

Inventing more and more terms for designating the former Soviet or, in a wider sense, former socialist space and individual is a thankless task, especially within the framework of the modern paradigm of knowledge production, where everything is measured in terms of the temporal logic of linear progression: premodern, modern, postmodern or, in our case, pre-Soviet, Soviet, post-Soviet. The prefix “post,” as is the case with postcolonialism, does not allow us to move outside “progressism” and loses temporal and conceptual meaning, as it reveals its inability to describe the real, dynamic, and ambivalent relationships inside the world of the abolished modernity of state socialism and its ties with the remaining world system and neoliberal capitalism, the sole legitimate modernity since 1989. Even among those whose studies focus on the subjectivities, ontologies, and chronotopes of the world that has replaced the system of state socialisms there is no consensus regarding what exactly they (we) explore. Some academics stick to the idea that Soviet remains the most important element of post-Soviet and that socialist ideology is the core of the postsocialist. Others rightly complain that the socialist world has become a void, a second-rate region, a type of a new/old periphery. Some convert politics into geography and geography into chronology and vice versa, further complicating the already complex tangle of notions and ideas dealing with socialist modernity and what grew from its ruins. Moreover, it is not clear what connects us today: is it language or nostalgia for the past, for the illusory simplicity and cordiality of human relations or the holism of pseudo-imperial greatness, which substituted or glued together ethno-national identities?

To navigate this intricate network, it makes sense to return to the moment of the shift from cold war discourses to the narratives of neoliberal globalization in its triumphant, and now sinister, guises. The impetus for the transition from decolonization to decoloniality (with the emphasis on epistemology) was the understanding that the state cannot be democratized and decolonized (Aníbal Quijano). It occurred at the exact moment when socialist modernity “suddenly” ended and Francis Fukuyama announced the end of history. At the same time, for the neoliberal and decolonial discourses of the future which emerged in the early 1990s in response to the end of the cold war, socialist modernity remained the proverbial elephant in the room, which no one paid attention to either in terms of knowledge production or in scenarios for the future.

The experience of this abolished, “erroneous” modernity is important for comprehending the present and future of humankind and other life forms on Earth, since it unveils specific intersections of ideological, racial, gender, affective, and other factors that are invisible and irrelevant for the global North and global South when considered separately. It also brings into being new, often centrifugal trajectories of the former Soviet republics and regions, connected to doomed attempts to overcome their inescapable marginality within the global system, while remaining a part of it. The lecture will focus on the key components of post-Soviet self-awareness, geopolitics, and the bodily politics of knowledge, being, and perception, while also articulating possible ways of building “deep coalitions” between former Soviet subjects. Not with the intention of going back to the model of a closed Soviet utopia but in order to enunciate a different political imagination marked by relativism and to return the future dimension to the world.

This presentation will be given via Skype.