In Igor Samolet’s project Architecture of Relationships, monumental modernist shapes and everyday things and narratives merge into a single whole—large objects displayed in the Communal Block of the Narkomfin Building.

Continuing the tradition of utopian hybrid spaces in the social construction projects of the 1920s and 1930s (garden city, communal house, kitchen factory etc.), they bring together the sublime and the everyday, the general and the particular, «expectations» and «reality».

The Narkomfin Building is a striking example of «transitional» architecture, which was designed to facilitate a smooth transition from bourgeois life in pre-revolutionary apartment buildings to, as Moisei Ginzburg wrote, «higher social forms of economy» in communal houses. He also called the building «experimental», emphasizing three experimental aspects in its design: social, architectural, and structural. Different apartment layouts, new building materials and technologies, and the partial communalization of everyday life were subject to research and later introduction into mass practice. The shared dining room, laundry, and roof terrace were to contribute to the creation of new social ties between tenants. Not all of the progressive ideas behind the project were destined for success: the compact and collective «new life» remained an ideological cliché, and the Narkomfin Building is a monument celebrating which celebrates it.

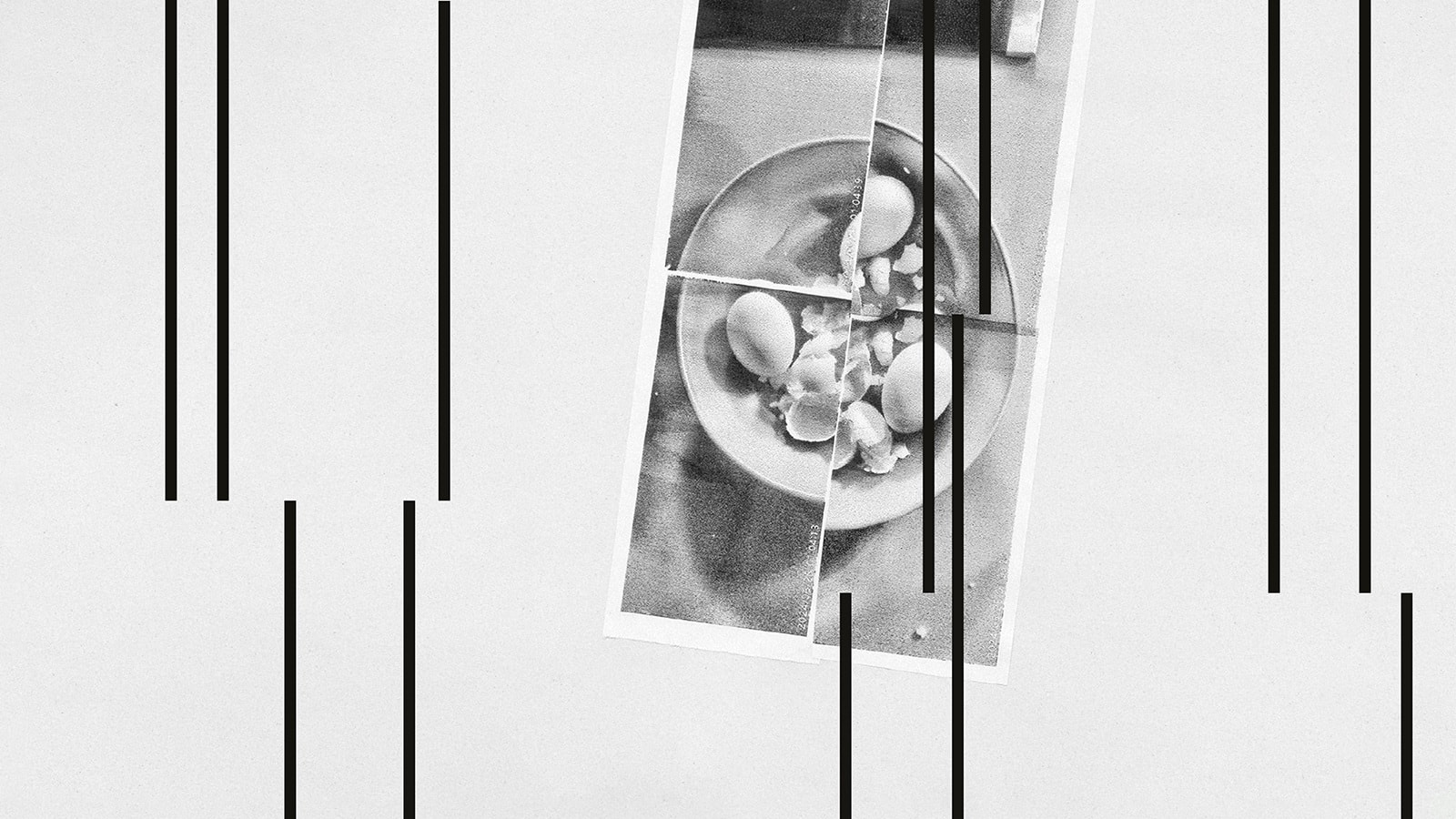

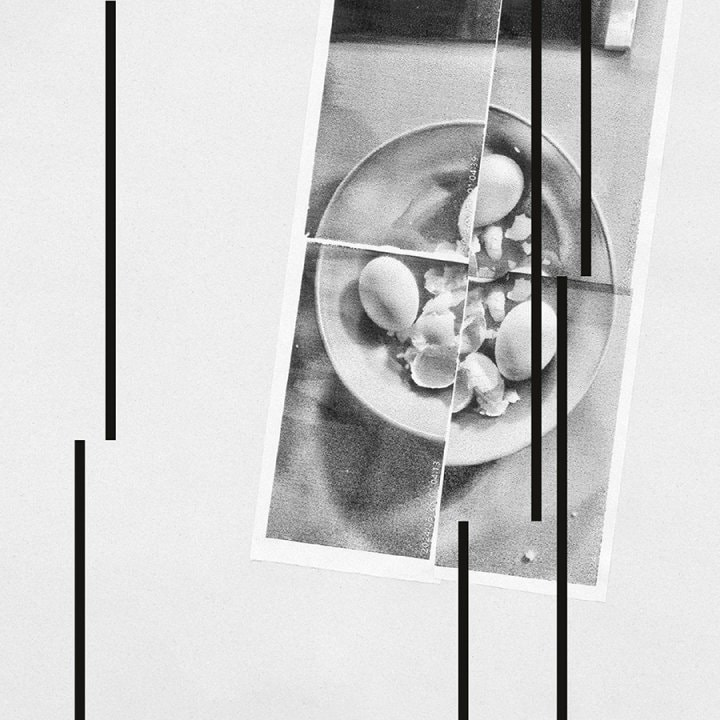

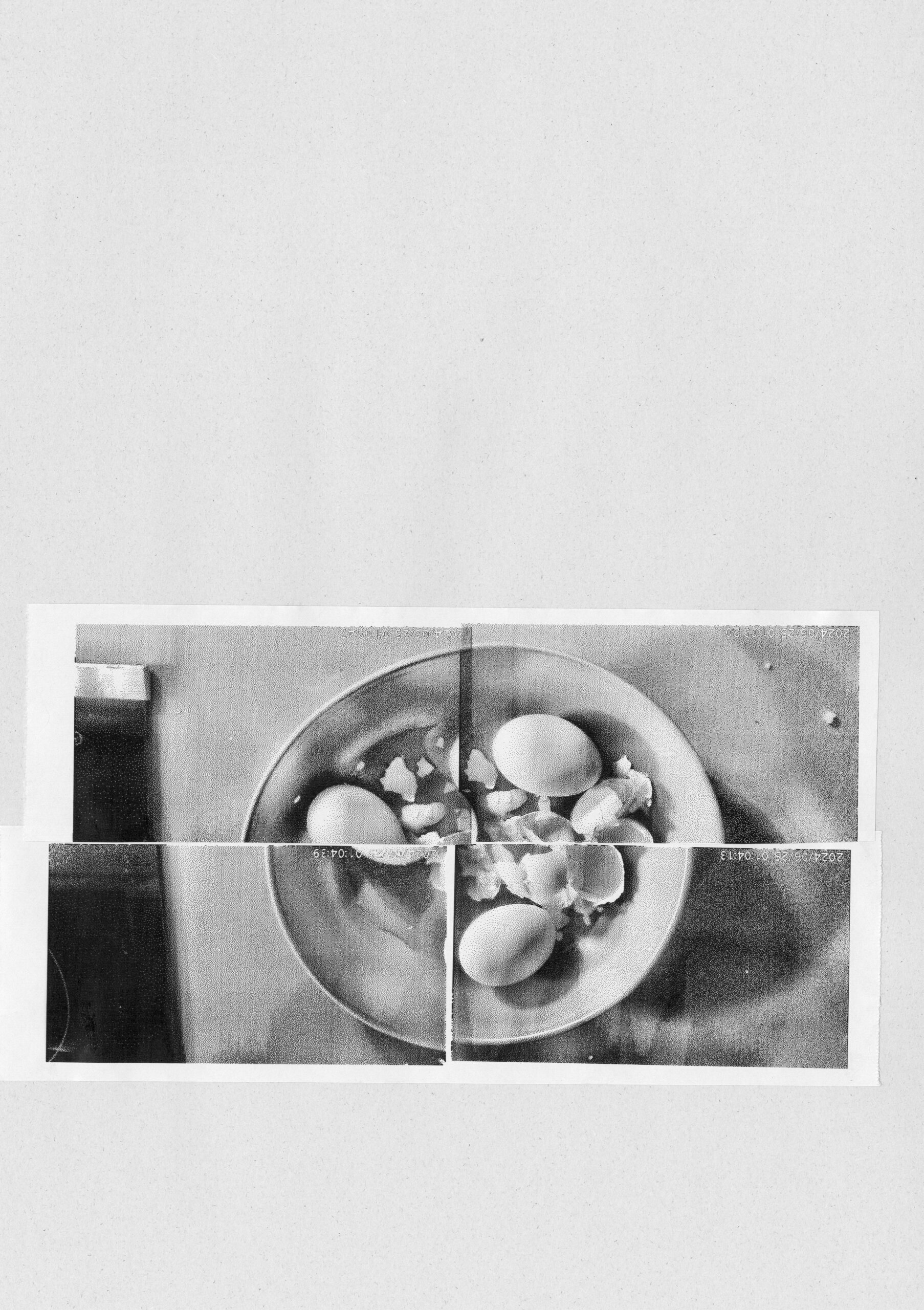

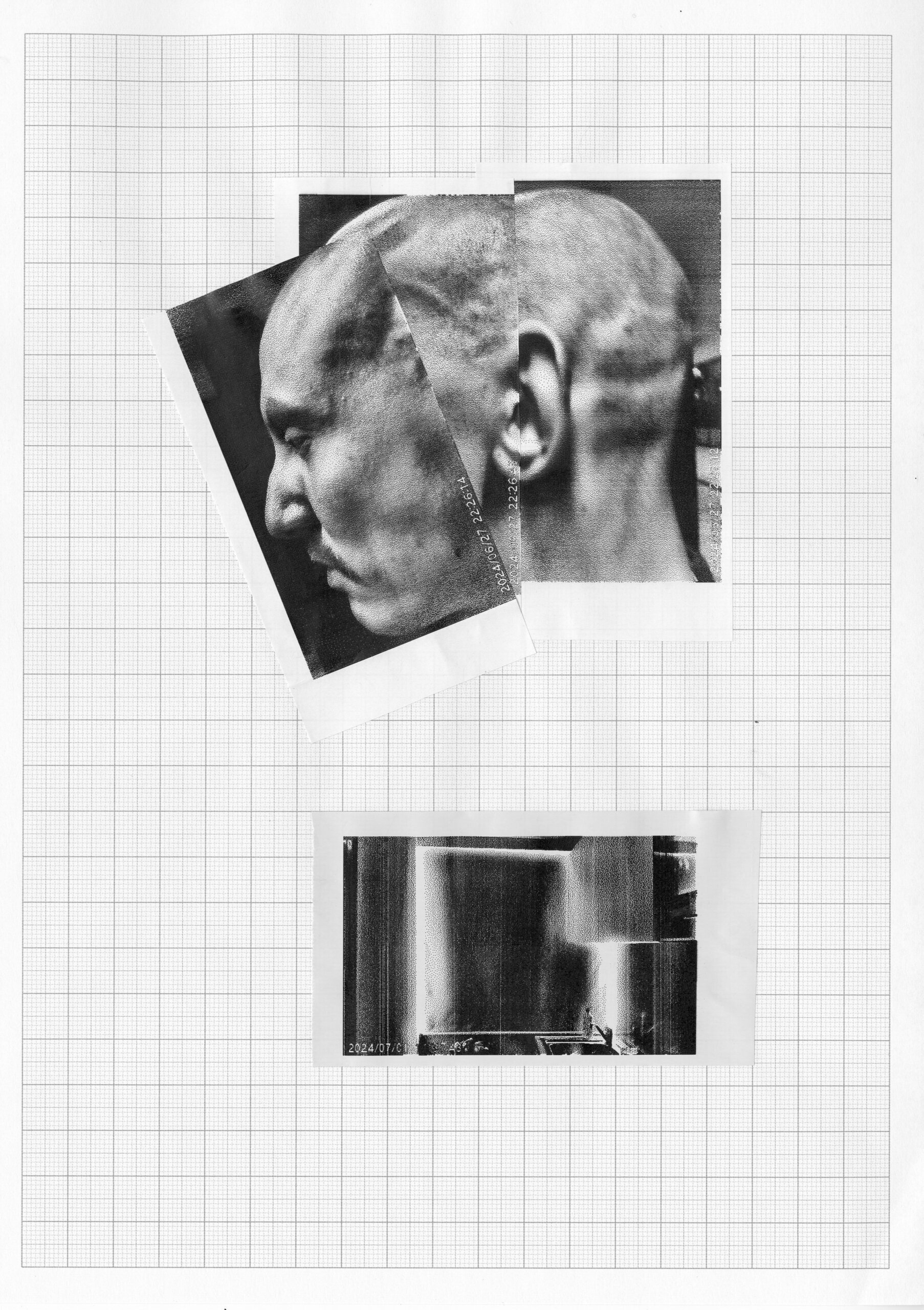

The austere forms of the monuments created by Igor Samolet symbolize the ambitious tasks once faced by the pioneers of Constructivism: to provide Soviet citizens with comfortable housing and workplaces; to build a social infrastructure and the «new» person by teaching them a new way of life and norms of behavior, thus anticipating the «bright future.» The furniture and household items—a cot or a washing machine— remind us of the necessity of satisfying basic human needs that do not always fit into the scenarios and housing conditions proposed by the architects. The bas-reliefs, made from instant-camera photographs Samolet took while living in the building, reference commemorative plaques on the facades, but their protagonists are Samolet’s friends rather than famous residents.

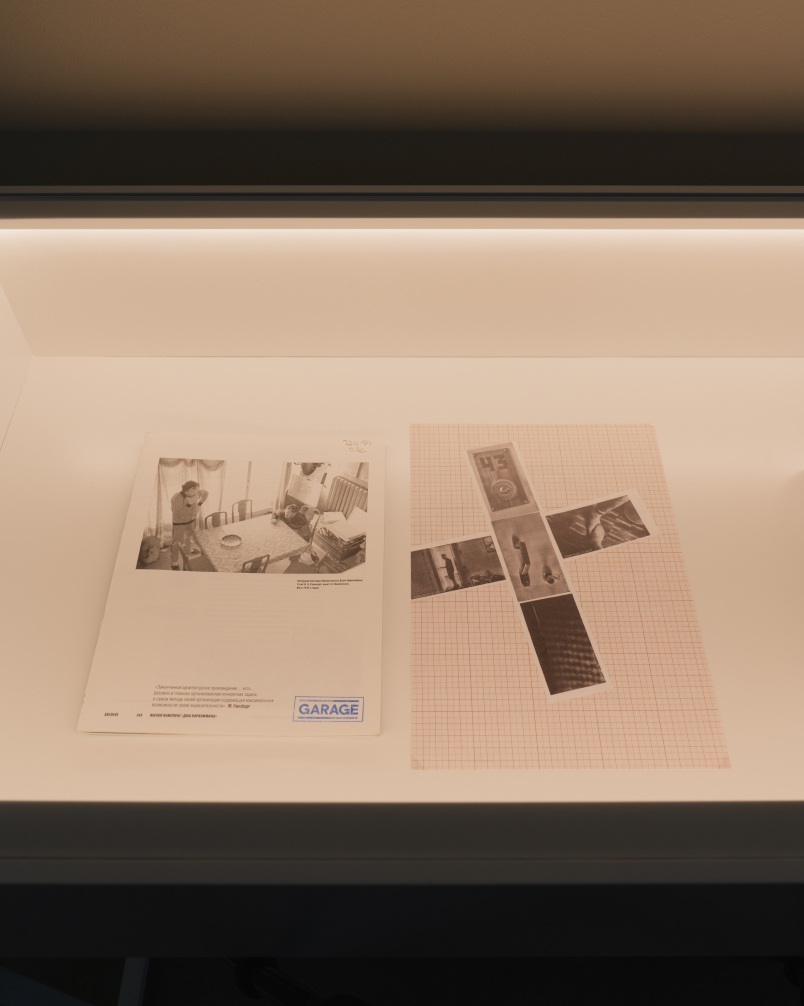

The P cell features graphic collages on drafting paper, assembled by the artist from his own black-and-white photographs, and a few surviving historical photographs of the residents of the Narkomfin Building.

The public program for the project includes mediations, workshops, and meetings with the artist.