Robert Longo: Quarantine Films

Film has always influenced my work. Cinematic elements—gestures, atmosphere, lighting, sets, the physical presence of the characters—have all contributed to the visual language of my work. Although I have made both film and performance art, I have spent the majority of my career producing work that is non-durational. Drawings and sculpture possess an incredible democracy that does not rely on the narrative structure of film. Yet, the power of cinema is undeniably singular and will continue to inspire me and my work.

All About Eve (1950), Joseph L. Mankiewicz

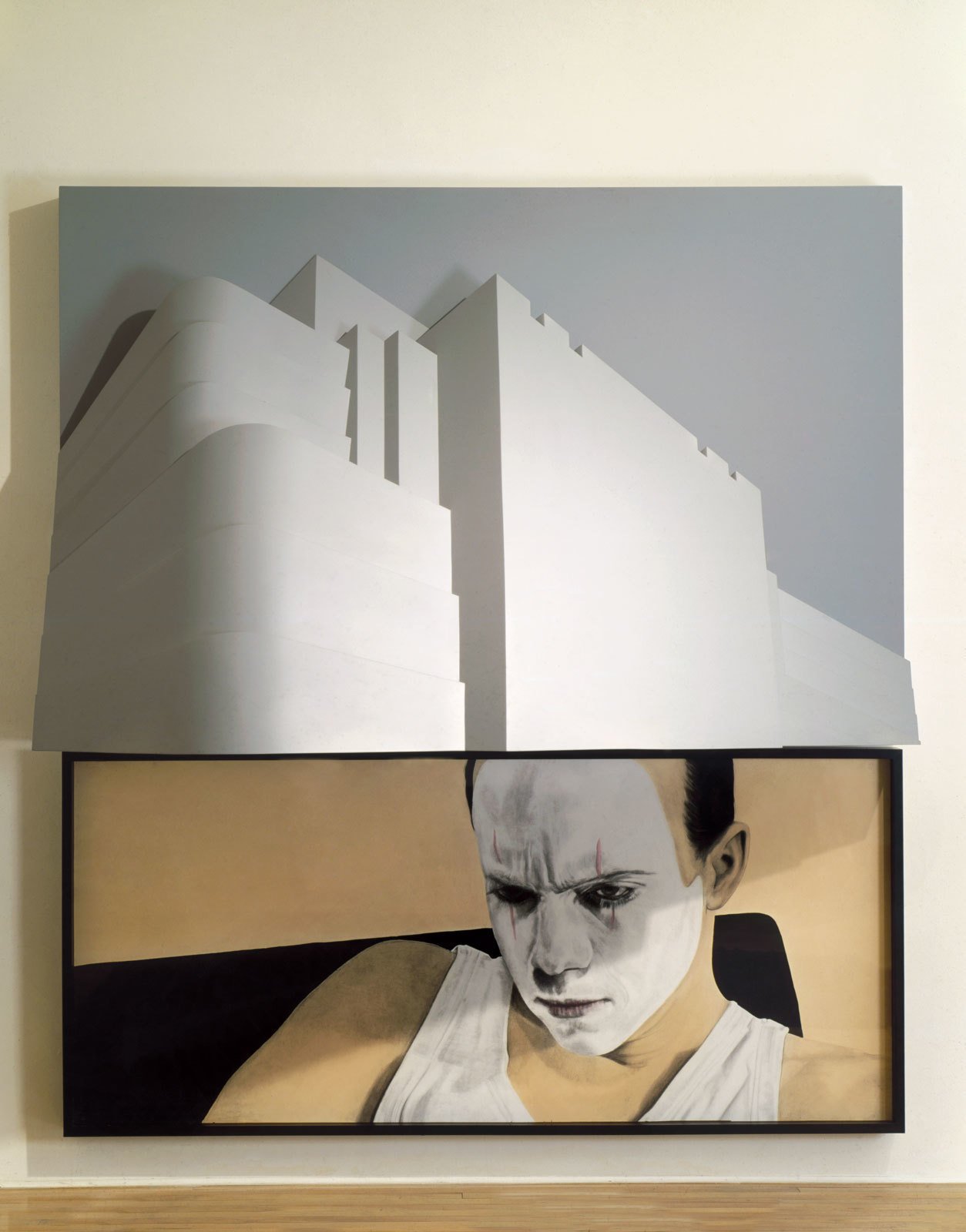

Image 1:

All About Eve (1950)

Dir. Joseph L. Mankiewicz

Image 2:

Pressure (1982–83).

Painted wood with lacquer finish, and charcoal, graphite, and ink on paper, 102 3⁄8 x 90 x 36 1⁄2” (260 x 228.6 x 92.7 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York

Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York

This Bette Davis classic tells a story of ambition, ego, and sabotage. Davis plays aging actress Margo Channing trying to stay relevant, while a younger actress, Eve (Anne Baxter), feigns adoration in an attempt to steal Margo’s upcoming role. I see the history of art as a series of rungs on an ever-extending ladder that each artist steps onto. As an artist, I hope to establish a rung that future generations will have the chance to step onto, to help them climb higher.

Bette Davis’ posture, the way she moves throughout the film, is mesmerizing and communicates so much of the character’s personality. The powerful physical presence of characters like Margo Channing have since lingered in my subconscious. I feel like she partly inspired my Pressure combine, which is composed of a sculptural element casting a shadow on the drawing below. The crux of the work exists within this oppressive interaction between the looming urban architecture and the slouching actor.

Beyond that sentiment, this film is simply fun. Davis’ character Margo is witty and sharp.

At one point, Margo quips to a successful playwright, “Lloyd, honey, be a playwright with guts. Write me one about a nice normal woman who just shoots her husband.”

The movie also features a young Marilyn Monroe. Apparently, it was the last time she used her authentic speaking voice on camera.

On the Waterfront (1954), Elia Kazan

Image 1-2:

On the Waterfront (1954)

Dir. Elia Kazan

Image 3:

Untitled (Potemkin, Black Square), 2015

Charcoal on mounted paper, 53 x 120 inches (134.6 x 304.8 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac; London, Paris, Salzburg.

Marlon Brando plays a man conflicted by loyalty to his brother and to a waterfront gang in Hoboken, New Jersey. The story communicates a feeling of solitude, and of being stuck. It is a story which, in a very basic sense, is rooted in its location, which is a very poignant feeling for me during this moment of isolation. Marlon Brando’s character is at such a dead end. He is truly doomed from the start.

The location of the waterfront is therefore so essential to the character’s story. Ships, which are intended to travel, are moored up at their docks, floating with no chance of forward motion.

The Night of the Hunter (1955), Charles Laughton

Image 1-2:

The Night of the Hunter (1955)

Dir. Charles Laughton

Image 3:

Untitled (North Cathedral), 2009.

Charcoal on mounted paper, 117 x 306 inches (297.2 x 777.2 cm).

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Image 4:

Untitled (Nathan Bedford Forrest Statue Removal; Memphis, 2017), 2018.

Charcoal on mounted paper, 70 x 120 inches. (177.8 x 304.8 cm).

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

The Night of the Hunter is one of the most quintessential Film Noirs. Robert Mitchum as the villain, posing as a preacher, is extraordinarily frightening. He possesses the perfect balance of charm and betrayal. Also, his Love / Hate knuckle tattoos are iconic. The tattoos and their accompanying “story of Good and Evil” monologue are referenced in Do the Right Thing (the tattoos taking the form of brass knuckles). The German Expressionist visuals of the sets, lit to create sharp angular shadows, have always stuck with me. The film’s flat minimal sets feel like those of a theatrical production, and they have greatly influenced my approach to composition.

Seven Samurai (1956), Akira Kurosawa

Image 1:

Seven Samurai (1956)

Dir. Akira Kurosawa

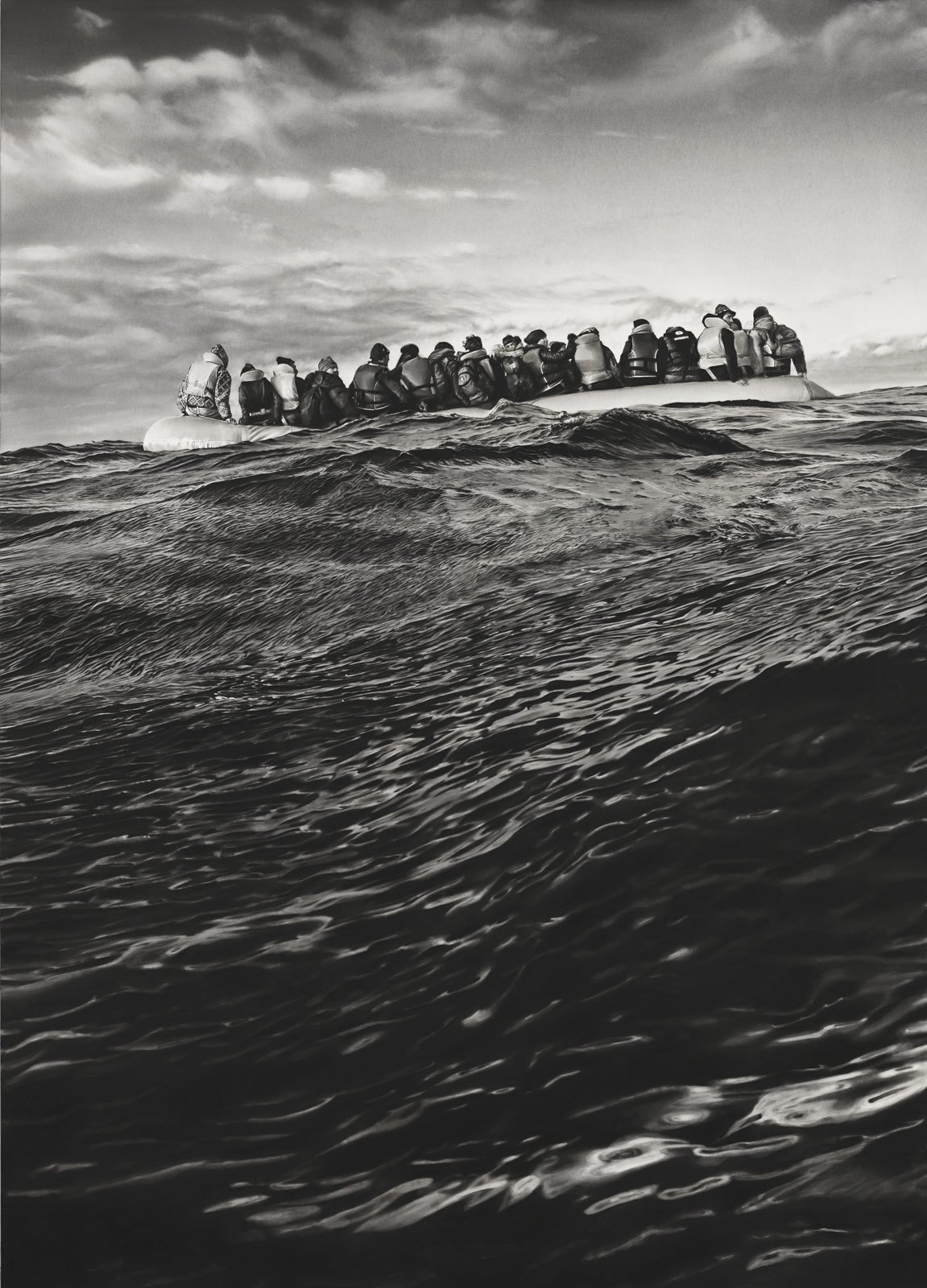

Image 2:

Untitled (Raft at Sea), 2016–2017.

Charcoal on mounted paper, 140 x 281 inches (355.6 x 713.7 cm).

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Image 3:

Detail of Untitled (Raft at Sea)

Kurosawa is one of the greats. He was both influenced by, and in turn influenced Westerns.

Seven Samurai directly inspired John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven (1960).

The story is an iconic archetype of small group of good defends vulnerable community against powerful evil empire, a tale as old as time.

I try to address images of sacrifice and humanity in my work. My charcoal drawing pictured here is based on an image I found in a Doctors Without Borders pamphlet of a group of sub-Saharan refugees on a raft in the Mediterranean Sea. I spoke to the photographer Santi Palacios, and he detailed the brutal circumstances. I bought the rights to the image and added 10 feet of water to create an empathetic sensation for the audience, as if they are in the water with them, fighting with them.

Nights of Cabiria (1957), Federico Fellini

Image 1:

Nights of Cabiria (1957)

Dir. Federico Fellini

Image 2:

Untitled (X-Ray of Bathsheba at Her Bath, 1654, After Rembrandt), 2015- 2016.

Charcoal on mounted paper, 70 x 70 inches (177.8 x 177.8 cm).

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac; London, Paris, Salzburg.

The film’s protagonist, played by Giuliette Masina, takes up a tremendous amount of space. She truly commands the camera. A Chaplin-esque prostitute, her mannerisms are charming and exaggerated. Fellini never shied away from amplifying strong female characters. Throughout art history, art about women has been fraught with the problem of the male gaze, the problem of reducing a woman to her objecthood rather than asserting her agency. I am interested in how male artists have grappled with this.

Since 2015, I have been making charcoal drawings based on the X-rays of art historical works, a series I call “Hungry Ghosts.” The conservators at many art institutions—the Museum of Modern Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Louvre, the National Gallery in London—have generously helped me to access images of X-rays and have provided me with an intimate view of the processes of artists such as Rembrandt, Manet, Van Gogh, Da Vinci, and Titian. Rembrandt’s Bathsheba at Her Bath (1654) tells the Old Testament story of King David seeing a bathing Bathsheba, and subsequently summoning her and sending her husband to war. In the final painting, Rembrandt presents Bathsheba melancholic, nude, and despondently awaiting her fate. My charcoal drawing Untitled (X-Ray of Bathsheba at Her Bath, 1654, After Rembrandt) reveals that, as shown by the painting’s X-ray, Rembrandt initially painted Bathsheba with her head raised into a more assertive position, her body covered. By presenting the interior view of the painting, I am able to address the artist’s internal struggle.

Sweet Smell of Success (1957), Alexander Mackendrick

Image 1:

Sweet Smell of Success (1957)

Dir. Alexander Mackendrick

Image 2:

Untitled (Statue of Marianne; Paris, France; December 1, 2018), 2019.

Charcoal on mounted paper, 85 x 131 1/2 inches (215.9 x 334 cm).

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

This film effectively epitomizes a specific time and energy in New York City. Telling the story of an aggressive pursuit of power, Mackendrick employed the visual language of classic Film Noir and German Expressionism, two movements which directly influenced my use of chiaroscuro in my work.

Black and white has always visually represented truth to me, perhaps because it is the aesthetic of journalistic photography. Many of my recent charcoal drawings are inspired by political images from mass media, such as this image of the Arc de Triomphe’s statue of Marianne, which French protestors smashed amid institutional frustrations in November 2018.

Yojimbo (1961), Akira Kurosawa

Image 1:

Yojimbo (1961)

Dir. Akira Kurosawa

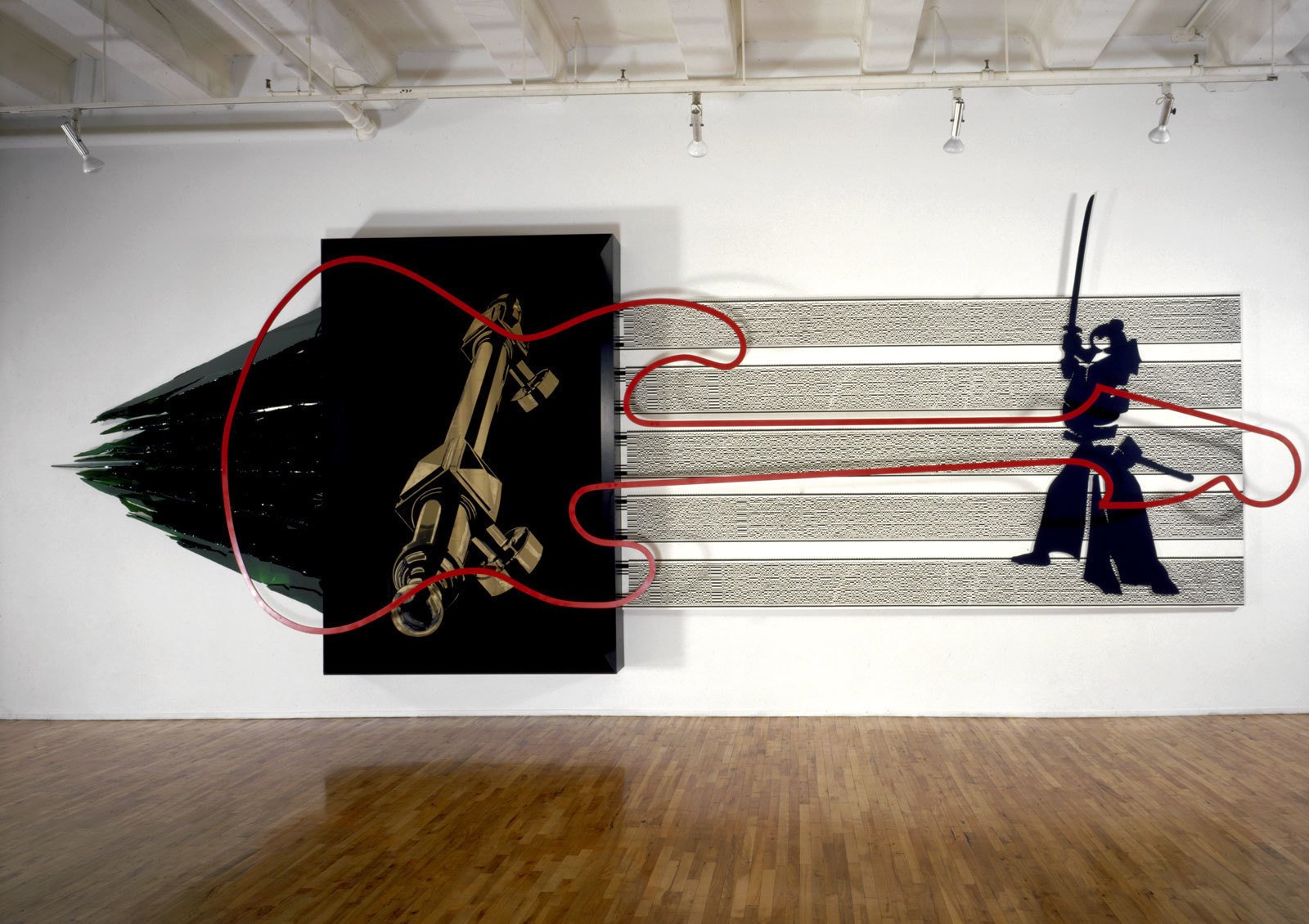

Image 2:

Samurai Overdrive, 1986.

Plexiglass, brass, steel, wood, silkscreen on canvas; 126 x 354 x 13 inches (320 x 899 x 33 cm).

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Kurosawa’s quintessential samurai movie (remade by Clint Eastwood as A Fistful of Dollars in 1964), the samurai Yojimbo—which translates to “bodyguard”—follows a nameless samurai caught between the silk and sake merchants of a Japanese village. The samurai ends up pitting the two against one another, ultimately revealing the flaws of the money hungry community.

During one scene in the film, a young gangster shows up with a pistol to a sword fight, thereby throwing the balance of power. This scene influenced my Samurai Overdrive combine, where a samurai character disconnects a field of technology, represented by blocks of computer text.

The Misfits (1961), John Huston

Image 1:

The Misfits (1961)

John Huston

Image 2:

Untitled (Torn Flag), 2018.

Charcoal on mounted paper, 70 x 93 inches (177.8 x 236.2 cm).

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

The Theater of Westerns is rooted in classic Americana, the American Dream. The Misfits presents a story of—well—misfits: an aging cowboy (Clark Gable), a divorcee ex-stripper (Marilyn Monroe), a WWII vet (Eli Wallach), and a former rodeo rider (Montgomery Clift). The characters meet and begin capturing wild horses. The good guy cowboy in a white cowboy hat was an icon of American culture for decades.

But in the early 1960s, that American hero icon began to fall apart.

What is most intriguing about this film is the blurriness between the film and reality. Not only are the characters a bit of a mess, but the actors themselves soon unravel. Just after filming, Marilyn Monroe and the film’s screenwriter Arthur Miller divorced. A year and half later, Monroe died. Clark Gable died two weeks after filming. It’s a very bizarre unintentional breaking of the fourth wall. I consider my work to exist between representation and abstraction: between reality and mythology.

La Jetée (1962), Chris Marker

Image 1:

La Jetée (1962)

Dir. Chris Marker

Image 2:

Installation View, “Men in the Cities,” Triptych.

The Pictures Generation, 1974– 1984 Great Hall, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; New York, NY; 2009.

Photographer: Eileen Travell.

© Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

While I was in school at SUNY Buffalo, I worked for structuralist filmmakers, like Hollis Frampton and Paul Sharits, and their work greatly influenced my understanding of composition and narrative. During this time, I also first encountered La Jetée, Chris Marker’s masterpiece of essay filmmaking. Marker composed this piece almost entirely of still images, detaching it from place and time. This film greatly influenced my Men in the Cities drawings, in which I isolated figures against their backgrounds, thereby presenting them as abstract symbols void of location. This film has had a tremendous impact on my visual memory.

Contempt (1963), Jean-Luc Godard

Image 1:

Contempt (1963)

Dir. Jean-Luc Godard

Image 2:

Untitled (Gabriel's Wing), 2015.

Charcoal on mounted paper, 70 x 120 inches (177.8 x 304.8 cm).

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

A film about making a film, the story parallels The Odyssey, and tells the story of a screenwriter struggling to work with a cocky American producer (Jack Palance) and a director (played by the legendary German Expressionist director Fritz Lang), while fighting with his wife (Brigitte Bardot). The plot is ultimately about a misunderstanding, leading to the screenwriter telling his wife to leave with the American producer, resulting in tragedy: a deadly car crash.

However, above all, Contempt is simply beautiful. Bardot, Capri—it’s all gorgeous, and sometimes beautiful is all art needs to be.

The Wild Bunch (1969), Sam Peckinpah

Image 1:

The Wild Bunch (1969),

Dir. Sam Peckinpah

Image 2:

Untitled (Eric), from the series "Men in the Cities," 1979–83.

Charcoal and graphite on paper, 96 x 60 inches (243.8 x 152.4 cm).

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Image 3:

Untitled (Vietnam, 1968), 2017.

Charcoal on mounted paper, 80 x 120 inches (203.2 x 304.8 cm).

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Image 4:

Untitled (Bullet Hole in Window, January 7, 2015), 2015–2016.

Charcoal on mounted paper, 76 x 143 inches (193 x 363.2 cm).

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac; London, Paris, Salzburg.

Image 5:

Detail of Untitled (Bullet Hole in Window, January 7, 2015)

People die in the most violent ways in this film, in more violent ways than I had ever seen before. There’s a real animated dance of death choreographed here. Westerns like this one helped inspire my Men in the Cities series, in which I depicted my friends in the obscurity and void between dancing and dying.

In making this film, Peckinpah was inspired by the daily broadcast of violence of the Vietnam War. Coming of age during this time, I became particularly numb to the onslaught of violent images. My draft number was 11, and suddenly America changed for me from the good guys to the evil empire. I felt disillusioned, and so began my efforts to slow down the image storm we all experience daily. I seek to isolate images from television, newspapers, the Internet, and to arduously construct them out of charcoal, asking the audience to slow down and truly see what they are looking at.

The Godfather (1972) and The Godfather Part II (1974), Francis Ford Coppola

Image 1:

The Godfather (1972)

Dir. Francis Ford Coppola

Image 2:

Untitled (Vatican Bishops), 2015–2016.

Charcoal on mounted paper, 93 1/4 x 140 inches.

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac; London, Paris, Salzburg.

The Godfather and The Godfather Part II are the ultimate archetypes of morality, family, and loyalty. Rather than depicting a morality that exists plainly as good or evil, the film presents morality which exists in a gray area.

At the end of The Godfather the baptism of Michael Corleone’s godson occurs at the same time as murders he has ordered. It is a powerful image of hypocrisy or perhaps loyalty.

My large-scale charcoal drawing Untitled (Vatican Bishops) presents a nearly life-sized crowd of Bishops and with it a dilemma: do you see yourself standing amongst these consecrated figures or do you imagine yourself alienated from them?

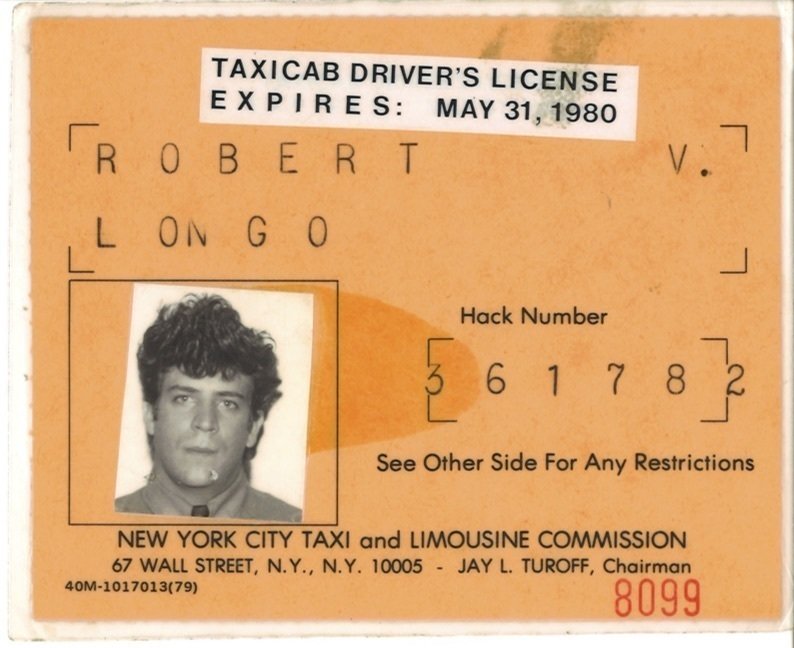

Taxi Driver (1976), Martin Scorsese

Image 1:

De Niro obtained his cab license while preparing for his role in Taxi Driver (1976) Dir. Martin Scorsese

Image 2:

Longo’s New York City TaxiCab Driver’s License, 1978–79.

When Cindy Sherman and I moved to New York City in 1977, Taxi Driver was one of the most exciting things to come out (that and punk music). I associate this movie with those early years in NYC. I actually worked as a taxi driver until 1979, when I had enough money to support my practice and pay my rent.

Apocalypse Now (1979), Francis Ford Coppola

Image 1:

Apocalypse Now (1979),

Dir. Francis Ford Coppola

Image 2:

Untitled (Riot Cops Engaged), 2018.

Charcoal on mounted paper, 70 x 146 inches (177.8 x 370.8 cm).

Courtesy of the artist; Captain Petzel, Berlin; Metro Pictures, New York.

To call Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now a highly visual film is of course an understatement. The yellow light—the color of decay—and colored smoke: orange, green, and purple (the third to foreshadow a character’s death).

But there is one particular scene that comes to mind: a night sequence toward the end of film where every shot is illuminated by gunfire and flares. Lighting a scene, seemingly exclusively, with tools of war is an unbelievably immersive tactic, and creates an incredible amount of tension.

The light in my work is always the white of the paper. So, in creating action via light, I must approach the image backwards. In traditional painting, the artist works from dark to light, whereas I work from light to dark, carving the image out of the archaic medium of charcoal, which is essentially dust.

Do the Right Thing (1989), Spike Lee

Image 1:

Do the Right Thing (1989),

Dir. Spike Lee

Image 2:

Untitled (Defaced Jewish Cemetery; Strasbourg, France; December 14, 2018), 2019.

Charcoal on mounted paper, 96 x 144 inches (243.8 x 365.8 cm).

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Image 3:

Untitled (1st Amendment), 2018

Charcoal on mounted paper, 70 x 99 inches (177.8 x 251.5 cm).

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Spike Lee’s masterpiece is still an epic punch in the gut, three decades later. By focusing on the racial tension in a single neighborhood over the course of single oppressively hot day, Lee’s portrayal of racism feels particularly brutal, inescapable. And 30 years later, black people are still getting killed while jogging. It is essential that we acknowledge the continued pervasiveness of racism.

Rage has been a real motivation for me in my work, especially as of late.

In December of 2018, amongst my stacks of old newspapers I saved to read, I discovered an image on page 9 of The New York Times. The striking image showed a group of tombstones in a Jewish cemetery near Strasbourg, France. The headstones had been vandalized with swastikas, nearly identical on each one, clearly all by the same Neo-Nazi’s hand. A member of my studio translated the worn, obscured Hebrew text beneath the spray paint as an effort to reinstate some humanity: the tombstone on the right belongs to a widow, in the center lies on an honest man who lived a long life, and on the left lies a religious man who died on Shabbat. In making this work, I hope to restore some love regardless of any effort of hate. As an artist, I feel a moral imperative, and I hope to make work that helps people to see better and to take a position.

Boyz n the Hood (1991), John Singleton

Image 1:

Boyz n the Hood (1991)

Dir. John Singleton

Image 2:

Untitled (St. Louis Rams / Hands Up), 2016.

Charcoal on mounted paper, 65 x 120 inches (165.1 x 304.8 cm).

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

This film is a genuine peek into a specific black experience in South Central L.A. in the 1980s. It is a powerful, early portrayal of hip-hop culture, and an important coming-of-age story. The film came out only months after the brutal attack of Rodney King, and provided an intimate, human view of gang violence. Cuba Gooding Jr. plays Tre Styles, who with the support of his father, is able to remove himself from committing a gang-motivated killing. Films like this one remind me of the importance of supporting visibility of the black man’s experience in America.

My drawing Untitled (Hands Up) depicts Kenny Britt, #81 wide receiver for the St. Louis Rams entering the field during the introduction ceremony on Sunday, November 30, 2014. Britt initiated the “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” gesture alongside four of his St. Louis Rams teammates (the Rams receiving corps). The five Rams players held up their hands while entering the field as a gesture of support for and solidarity with, the Ferguson community and protesters after the shooting by a police officer of unarmed teenager Michael Brown on August 9, 2014. The image of Kenny Britt reminded me of the equally historically important image of John Carlos and Tommie Smith on the podium at the 1968 Olympics, bravely holding their black-gloved fists in the air. It was a powerfully brave moment in American history.

No Country for Old Men (2007), Ethan & Joel Coen

Image 1:

No Country for Old Men (2007),

Dir. Ethan & Joel Coen

Image 2:

Untitled (Ferguson Police, August 13, 2014), 2014.

Charcoal on mounted paper, 86 x 120 inches (218.4 x 304.8 cm).

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; Petzel, New York.

Collection of The Broad Art Foundation.

There is a quiet violence in Javier Bardem’s character. A true relentlessness.

Music is essentially nonexistent in the film, adding to the film’s unbelievable tension so that even the crinkle of a candy wrapper in the Coin Toss scene is unexpectedly disturbing.

In my work, I often think about how to adjust the hierarchy of elements to pack the most punch, how to quietly sneak up on the viewer.

When I first saw images of the riots in Ferguson, Missouri, after Michael Brown’s murder on August 9, 2014, I thought the image was from Ukraine. I couldn’t believe I was looking at an American street. The police militarization enraged me. My Untitled (Ferguson Police, August 13, 2014) drawing shows a line of heavily armed, militaristic riot police in the foreground, while signs for McDonald’s and Exxon quietly loom in the background, reminding the viewer that this disturbing scene is indeed in America.

Get Out (2017), Jordan Peele

Image 1:

Get Out (2017),

Dir. Jordan Peele

Image 2:

Untitled (Statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee Covered; Charlottesville, Virginia; August 2017), 2018.

Charcoal on mounted paper, 120 x 95 1/4 inches (304.8 x 241.9 cm).

Courtesy of the artist; Captain Petzel, Berlin; Metro Pictures, New York.

Peele’s Get Out is truly one of the most effective feats of filmmaking of the decade. His treatment of audience expectations is gripping. What we anticipate to be ramping up to a typical “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” trope completely turns upside down, and takes us with it.

This film is truly sinister, surreal, and ultimately hilarious.

I want to believe that art has the capacity to help people understand things, or at least to look at things a little bit differently.

It can be too easy to forget that America was born out of the most atrocious crimes. And one of the biggest failings of this nation is its continued refusal to truly address slavery and make reparations. My large-scale charcoal drawing may appear at first to be simply a rendering of a plastic tarp. It is actually a depiction of the covered statue of Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, Virginia. On August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville, a group of white nationalists protested the proposed removal of a monument to Robert E. Lee, the top Confederate general, still revered by many Americans. The rally turned violent, leading to 34 injuries and one woman dead. The monument to Lee remains standing. I think people forget that the monument is still there.

Joker (2019), Todd Phillips

Image 1:

Joker (2019),

Dir. Todd Phillips

Image 2:

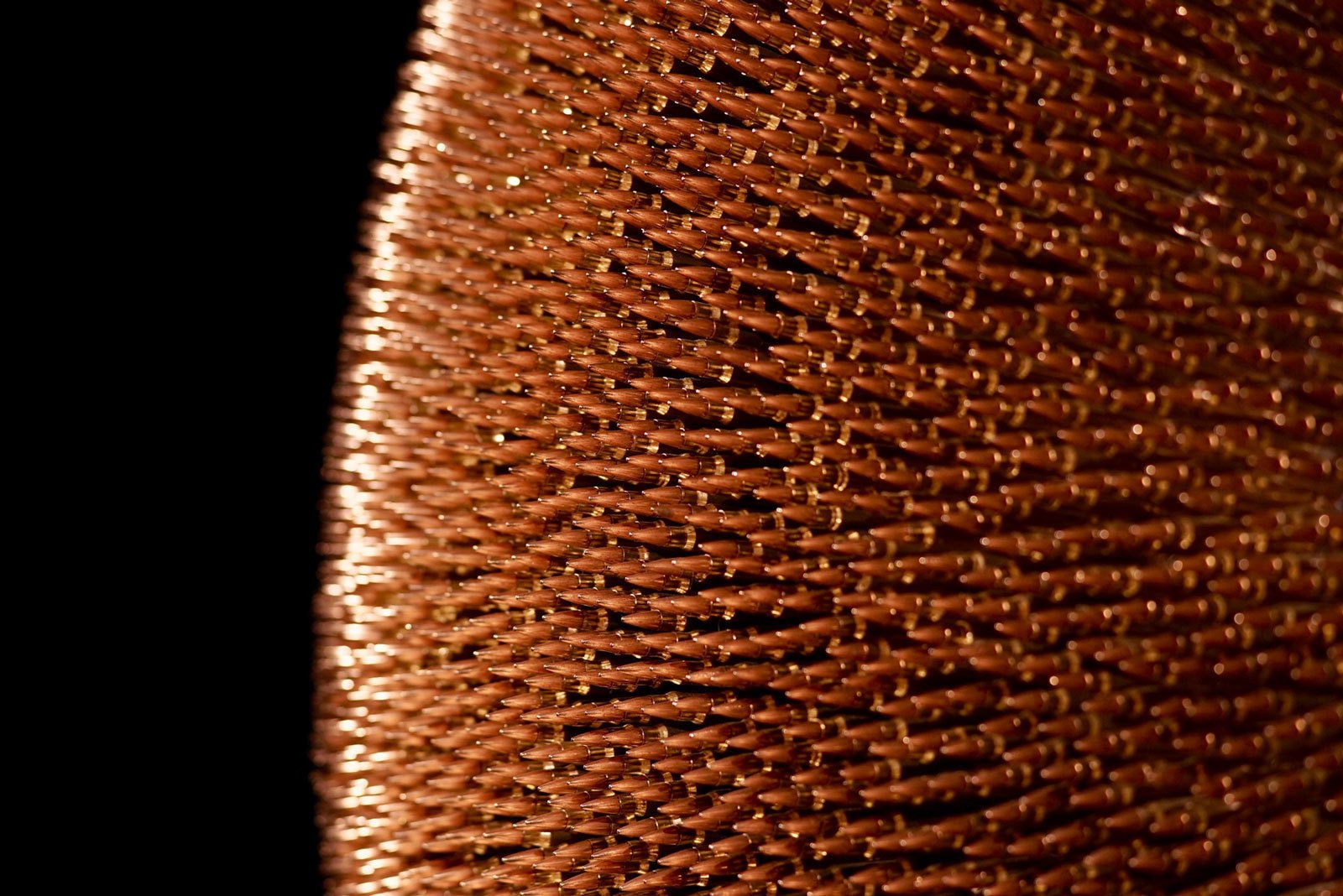

Detail of Death Star 2018.

Image 3:

Death Star 2018, 2018.

40,000 .308 FMJ 150 grain brass, copper, lead bullets; cast aluminum; steel Ibeams; steel chain, 254 1⁄2 x 254 1⁄2 x 144 inches (sphere measures 77 inches diameter).

Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York;

Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac; London, Paris, Salzburg.

This film was so poignant and troubling, and it’s been a long time since a film’s reception has been so controversial. Joaquin Phoenix was spectacular, and that dance down the steps was incredibly disturbing. But what interests me the most is how the film addresses mental health in this country along with the ease with which a person dealing with mental illness can get access to a gun.

I’ve supported common sense gun reform in America for a long time. In 1993, I made a sculpture made of 18,000 38-caliber bullets covering the surface of a 36-inch diameter sphere, suspended by a steel armature. This was my first work entitled Death Star, and the 18,000 bullets corresponded to the approximate number of gun-related deaths in the U.S. in 1993. The idea began when my 15-year-old son came home and excitedly announced that one of the kids at the local basketball court had during a fight pulled a gun. His excitement alarmed me, and I feared my children may be seduced by guns as seemingly “cool” objects. I started investigating guns and making work that amplified and isolated the form of the gun and the bullet, forging a new visual impact. This became my series called “Bodyhammers.” Since 1993, the gun violence crisis in America has dramatically worsened, and in 2018, I made a new version of this same work. With each bullet corresponding to the approximate number of gun-related deaths in the U.S., in 2017, my 2018 Death Star consists of 40,000 30-caliber AR-10 rifle bullets and takes on a new, more oppressive scale: a 72-inch diameter. When the audience first encounters the object, they are not quite sure what it is. It looks innocuous, a disco ball perhaps. Yet, upon closer inspection, when the bullets come into focus, the effect is arresting. Making art out of disaster in and of itself is a tradition I feel comfortable participating in, but it is not enough. I donated 20 percent of the sale of Death Star 2018 to Everytown for Gun Safety, a U.S. based nonprofit advocating for gun control.