Auguste Perret (1874–1954) pioneered the implementation of reinforced concrete in architecture and kept on using this material throughout his life, claiming that “my concrete is more beautiful than stone”.

Perret combined modern construction solutions with the principles of French classicism by adding the sixth—concrete—order to the existent five classical ones. As he strongly believed that “decoration always hides an error in construction”, Perret kept concrete surfaces open—to reveal interesting textures resulting from the use of formwork and an attractive color pattern made possible thanks to adding various natural components to the cement mix. Accurate engineering calculations allowed him to achieve maximum space with minimum materials. Perret’s style is associated with proportionally harmonious, clearly readable, and well lit spaces: he considered these qualities to be crucial for creating a psychologically comfortable human environment.

Perret entered into an ardent debate with Le Corbusier (who worked in his older colleague’s studio in 1908) who, he believed, merely pretended to value functionality over everything else and in fact sacrificed the durability of an architectural construction and the comfort of its inhabitants for his formal experimentations. For instance, external walls without cornices will soon require a repair, chimneys that are too thin and short will not be able to disperse the smoke, and, most importantly, ribbon windows so beloved by Le Corbusier provide certain spaces with too much light and others with too little. Perret preferred vertically elongated windows which he considered an integral element of an apartment building, allowing for an ideal organization of both lighting and proportional decomposition of walls.

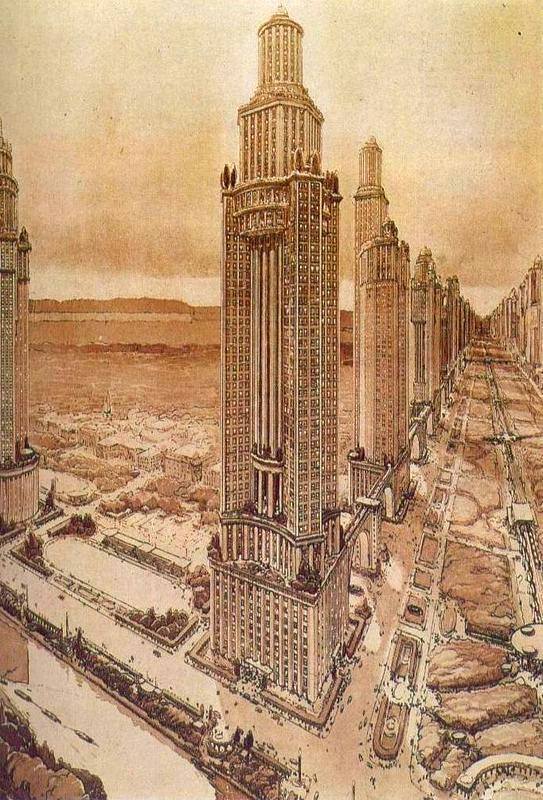

Although Le Corbusier considered his former teacher a retrograde, he enthusiastically appropriated some of his ideas, for example the conceptual project City-towers which was created by Perret in 1922 and became a starting point for Le Corbusier’s famous Contemporary City for Three Million Inhabitants (1924). Perret built enough towers in his career as he thought them to be a necessary element of the urban silhouette. Narrowing upwards, most of them resemble the towers of medieval cathedrals, not citing Gothic architecture straightforwardly however. Perret’s highest towers are the 27-storey residential skyscraper in Amiens (104 meters, 1942–1951) and the tower of St. Joseph’s Church in Le Havre (107 meters, 1951–1957).

The reconstruction of Le Havre’s city center ruined by the bombing during the Second World War became the last and largest project of Auguste Perret (construction works continued into the next ten years after his death). Here, the architect had the opportunity to fully implement his urbanistic ideas, shaping the city’s silhouette by making clearly readable accents and emphasizing local specificity by connecting the ensemble of the main square with the English Channel. The main goal of the postwar reconstruction was to quickly fulfil the loss of residential housing, so Perret was building budget social housing using industrially-produced reinforced concrete panels. In terms of proportions and color patterns, the use of under-roof cornices and colonnades on the ground floor however, these constructions demonstrated continuity with the nineteenth-century French housing tradition. The Le Havre reconstruction was an influential project inspiring architects and urban planners in other countries, including the Soviet Union. In 2005, the architectural ensemble created by Perret in Le Havre was added to the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.