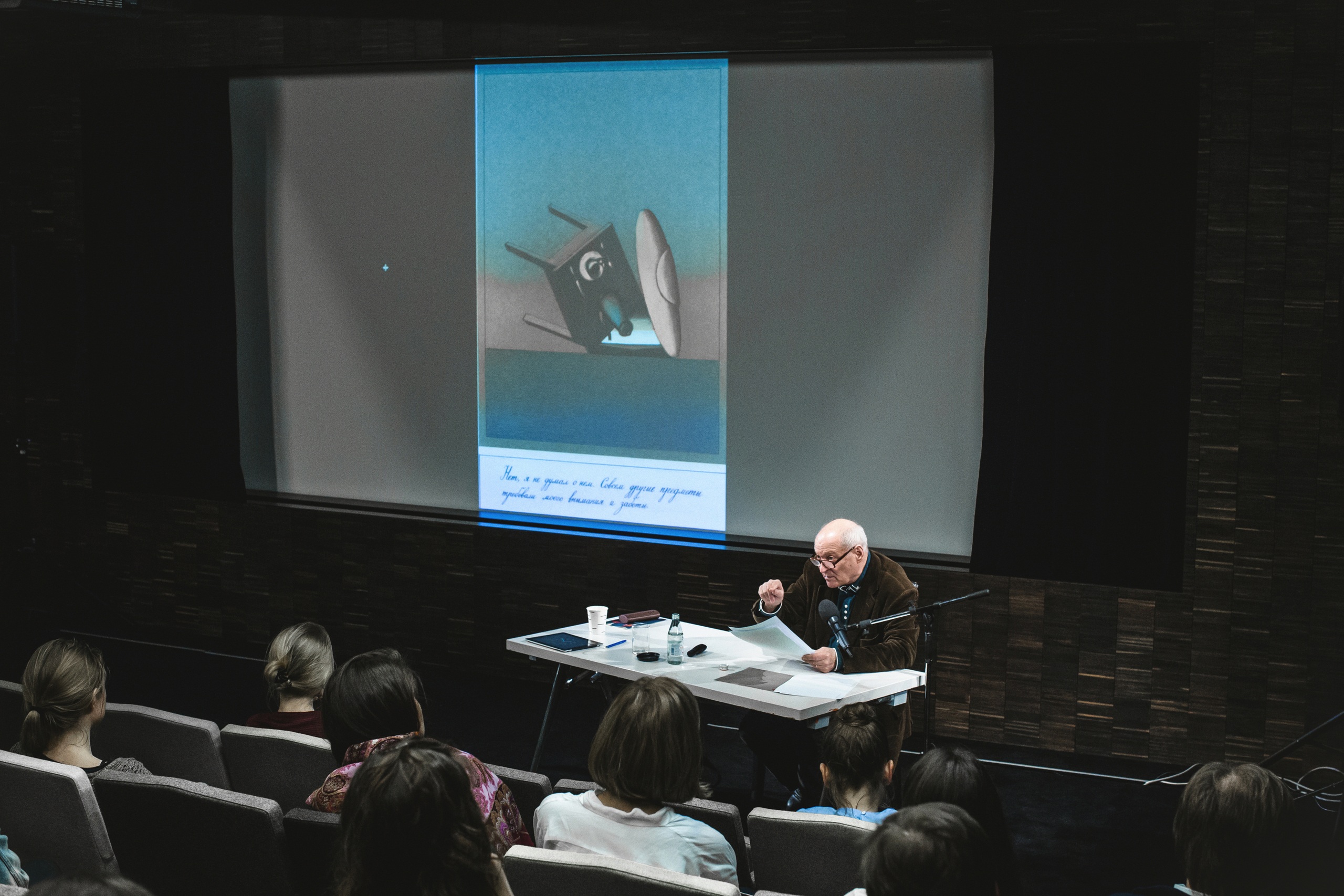

In conceptual art, and specifically in the practice of Moscow Conceptualist Viktor Pivovarov, what is most important: image or word? Art historian Mikhail Allenov discusses this question in his lecture at Garage.

Birds flew down to peck at the grapes painted by ancient Greek artist Zeuxis, but human behavior is determined by our skill, ability, or talent to distinguish things from their images. Representation is image conceived in some invisible virtual space, yet manifested in reality. A word inscribed into a painting complicates it, making it look like a board, a poster, a thing, objectifying the field of pictorial convention.

In conceptualist practice, the aesthetic and plastic qualities of a board come together for the representational revelation of a canvas, liberated from the inertia of traditional painting. A board is a type of “open form,” i.e. an image open to word, and a word open to image, where both act as companions, as it were. But still, there is a question: which one is the cause, and which is the effect? Is it a board that primarily represents specific figurative compositions—or, rather, a board that carries verbal messages of text?

Although Viktor Pivovarov also refers to the visual structure of a board as to the epiphany of the new representation, in this lecture Allenov will argue that it’s not the board that initiates the union of word and image, but rather the word, in conjunction with image, which materializes the surface the image is painted on, alluding to the board as to just one of its creations. A board in this case becomes a variant of a plane, acting as a border, or an obstacle where we see something present here, while simultaneously realizing there is something else beyond—on the other side of it. The world, which the painting reveals and unfolds as the image and likeness of the visible world, transforms into a kind of Neverland whose contours are at best marked on this surface. As Pivovarov claims, objects represented that way “reveal the quality of a sign.” They suggest a plane perpendicular to the direction of the viewer’s gaze, i.e. shutting the perspective. Such a plane has many versions: a wall, a door, a gate, a board, a banner, a poster, a curtain, a school board, a book or an album page, a cover, a wrapper, a table or a diagram, a map, a display window, a screen, etc. In Pivovarov’s case, the logic inherent in the unfolding of this plane-obstacle image is amazing in the entire spectrum of the meaning-producing particles within the magic glass of an artistic mind. This is also known as creative insight.