Sharon Kivland

(b. 1955, Wiesbaden, Federal Republic of Germany; lives and works in London and Plouer-sur-Rance, France)

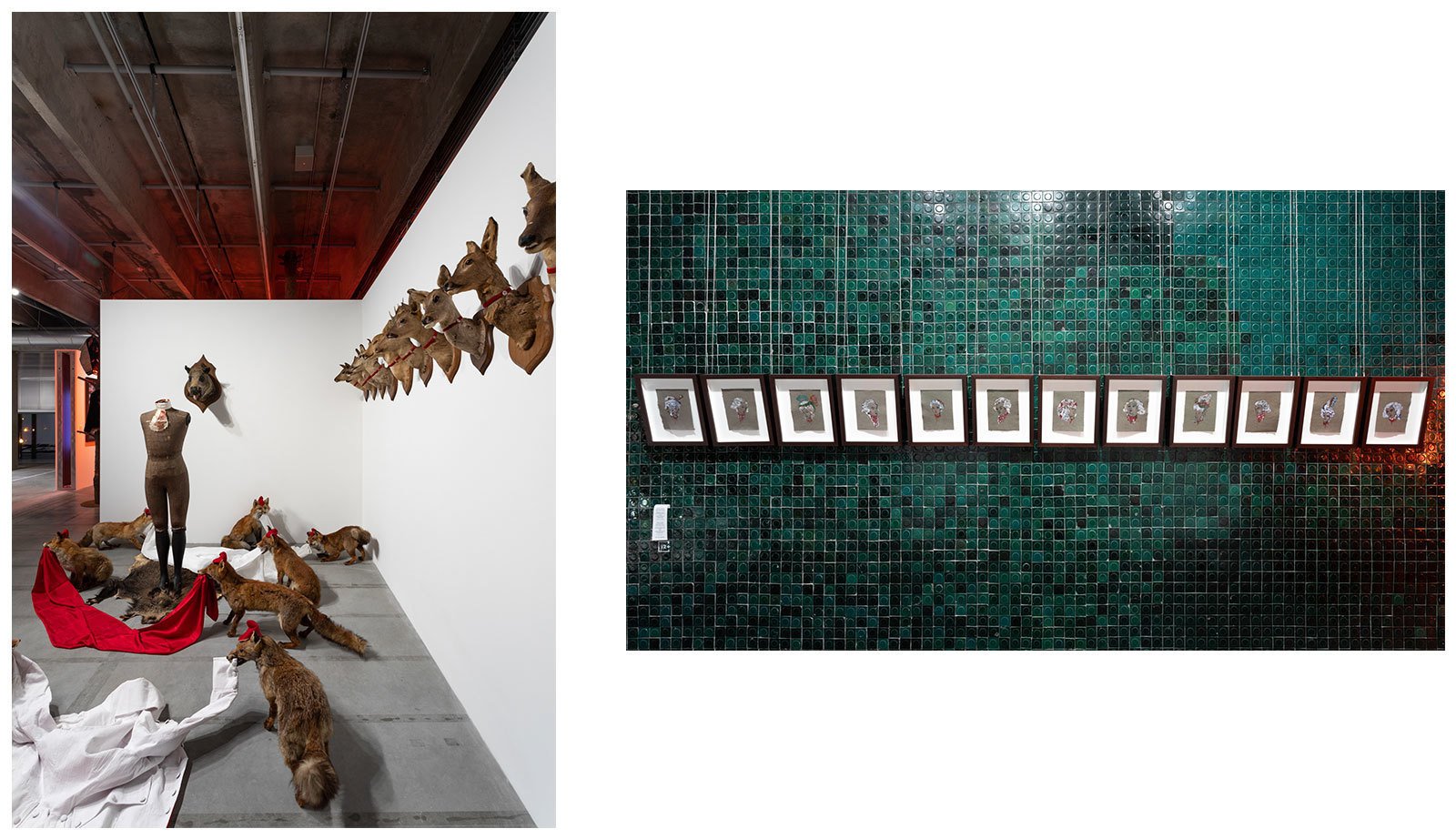

La terreur n’est autre chose que la justice prompte, sévère, inflexible, 2018

Installation

In collaboration with Clémentine Bedos, Marie-Andrée Bernard-Trébern, and Thomas Gaugain

Courtesy of the artist

The clothing historian Jennifer Craik believes that uniforms originate from the social need to identify the military and priests, to keep them apart from the masses. One might also say the opposite: once a group of people in any society sees itself as a collective moral authority and/or a supervisor of the public order, it comes up with a dress code, a kind of uniform. In her installation, which resembles a local history museum, the British artist Sharon Kivland allegorically narrates the French revolution through articles of clothing and accessories spontaneously adopted by the warring layers of society. Two foxes are dressed as sans-culottes, representatives of the lower classes who were the main supporters of revolutionary terror and its ideologist Maximilien Robespierre. (The costumes were made by the artist Clémentine Bedos.) Robespierre’s famous justification for the guillotine’s near non-stop deployment in 1792–1794 is the title of the installation. Sans-culottes wore pants as opposed to the knee-length stockings favored by the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy. After the revolution, representatives of other classes sympathetic to the regime also began wearing pants, thus creating the first political uniform. The other foxes proffer items of clothing characteristic of the “old order” (sewn by the dressmaker Marie-Andrée Bernard-Trébern) to a headless dummy sporting a jabot and lace (made by the artist Thomas Gauguin). The twelve deer wear red ribbons on their necks, as the participants of the “victims’ balls” allegedly did: these apocryphal events were sumptuous evening receptions for relatives of those guillotined.