Ethnography and Future Eves

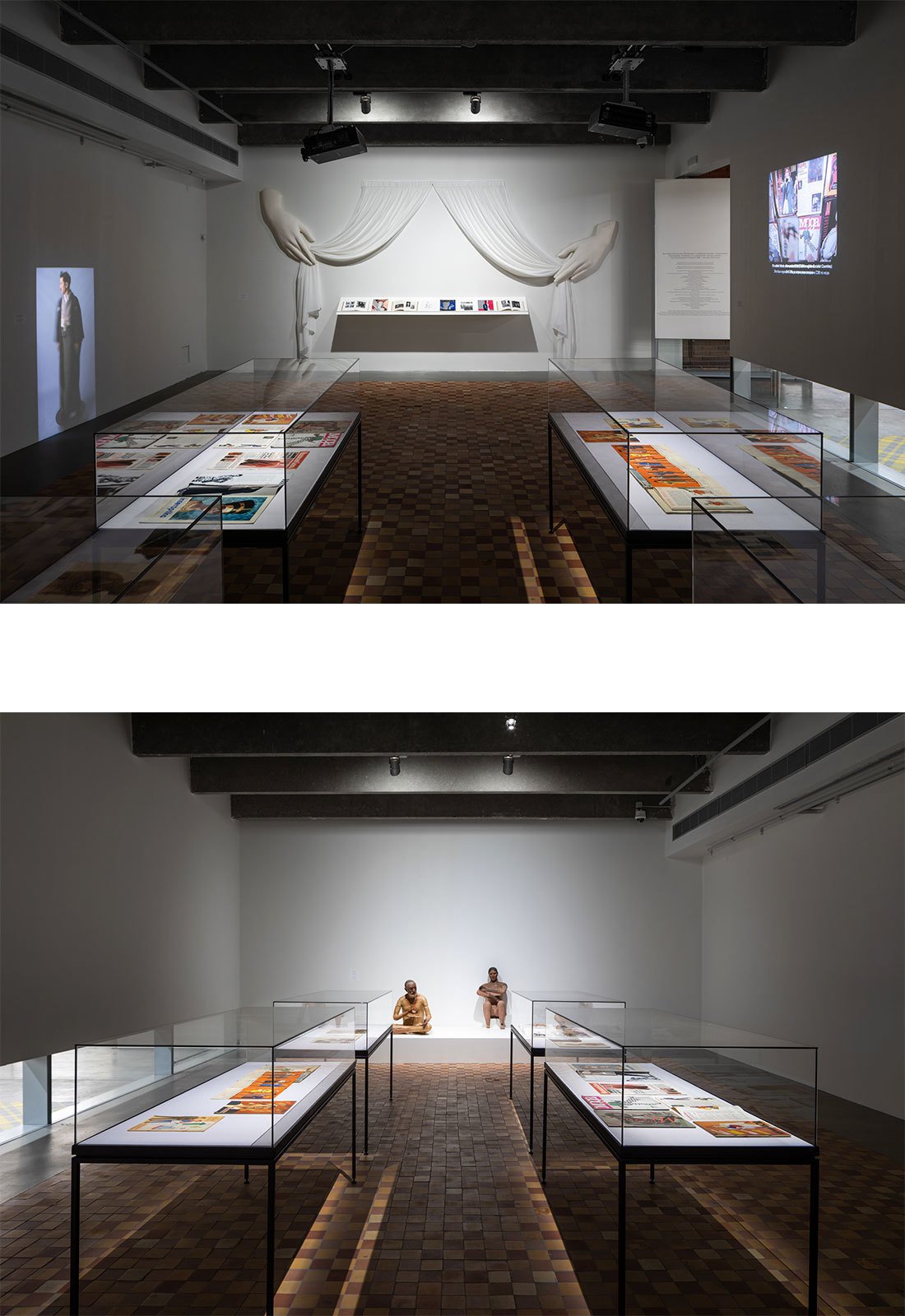

In this section you can see two polarized positions in relation to mannequins: fashion magazines and mannequin catalogues are contrasted with ethnographic figures employed in anthropological displays in the Soviet Union. But the section starts with another kind of contrast. Two video projections show opposite histories of fashion display from very different cultures. On the right you can see a 3D shoot of traditional Iki dolls from Japan, made by the famed artisan Yasumoto Kamehachi. On the left, a documentary produced for Passer-by tells the story of Lydia Orlova, the Soviet Union’s foremost fashion editor. These two videos present varying views on tradition and invention.

The magazines and brochures in the vitrines illustrate the moment in the late 1920s when fashion, painting, photography, illustration, and sculpture collided to produce a new aesthetic. Illustrators like Eduardo Benito, who produced covers for Vogue, connected the innovations of painters like Kazimir Malevich and sculptors like Constantin Brancusi, who abstracted and simplified the human figure, with the leading mannequin manufacturers of the day. Siegel was the first to develop stylized and abstract mannequins made from new materials. These mannequins formed part of elaborate sets at fashion fairs and in luxuriously designed sales catalogues and commercial brochures, which employed well-known photographers to showcase the mannequins modelling the clothes of famous fashion houses.

The lithe fashion models they produced could not be further from the kind of prosaic mannequin used in ethnographic displays. The mannequins you see here originate from the Russian Ethnographic Museum. They were made in the late 1920s by the Museum's artist, Konstantin Kavtaradze, who participated in field trips to Central Asia to get the types exactly right. The museum, now in its fifth or sixth wave of re-exposition, still views these mannequins as the best ones. The figures do not entice us to project our ideal selves and ultimately buy the garment they display. Their job is to reflect the typical features and “character” of various indigenous peoples. They often veer eerily close to taxidermy, and they are often packed densely in glass vitrines, situated somewhere between presentation and storage. This contrasts with the sense of life and vitality a more abstract display can evoke.

In this room you can also see Lydia Orlova’s personal archive of Soviet fashion magazines, and a sculpture of oversized hands made by Pavla Dundalkova. These hands frame the vitrine holding the fashion magazines and mannequin catalogues, to highlight their aura of luxury and prestige. Orlova’s archive is also placed here to make the connection with contrasting fashion magazines cultures. Plus this area is good for some quiet concentration. The museological setting venerates the magazines and places them in the context of adoration they deserve.