To celebrate the first year of Garage Library, which opened on December 11, 2014, members of Garage Research have each picked out a book they find important or interesting.

Garage Research team on books they find important or interesting

Selection by Evgeniya Abramova, Elena Ishenko, Valeriy Ledenev, Sasha Obukhova, Nastya Tarassova, and Anastasia Tishunina.

Steven Watson. Factory Made: Warhol and the Sixties

New York: Pantheon, 2003. — 490 pp.

Steven Watson’s take on Andy Warhol’s Factory, which reached the height of its influence between 1963 and 1968, is based on oral history—interviews and secondary sources like autobiographies, newspaper articles, and critical essays about Warhol’s works.

But how does one describe an art community’s practices without limiting one’s analysis to its aesthetics, production and distribution of art? How should one speak of amphetamines, homosexuality, transvestism, BDSM, pornography, prostitution, mental disorders, suicide, arrests, and other essential elements of this 1960s community’s life?

Watson seems to have done the impossible: he carefully presents the facts in full detail at the same time as he refrains from moral condemnation or dry academic language. Not romanticizing his characters and keeping a distance from them, he seems to be guided by Paul Morrissey’s words: “Andy never really thinks of stories. As soon as you take a storyline, you take on a moral position.”

For Watson, the Factory, which produced films like Blow Job, Kiss, My Hustler and The Chelsea Girls, was over on the day the radical feminist Valerie Solanas attempted to shoot Andy Warhol in 1968. From then on, the studio no longer made films and started making commercial art instead. However, the stories of people involved in the Factory continued, and Watson goes on to speak of how they returned home, got old, died and became the iconic figures we know today. Watson also speaks of how Warhol’s films today can only be found in the Museum of Modern Art’s film vault in Scranton, Pennsylvania. E.A.

Paolo Virno. A Grammar of the Multitude: For an Analysis of Contemporary Forms of Life

M.: OOO Ad Marginem Press, 2013. — 176 pp. Published in Russian by Garage Museum of Contemporary Art and Art Marginem Press.

This work by one of the key philosophers of the Italian left, Paolo Virno, was developed from his seminar at the University of Calabria in January 2001. That is why it is written in very simple, almost informal language, which might confuse the reader by promising an easy read or some kind of pop philosophy. In reality though, Virno’s simple and elegant way of speaking is informed by his philosophy and acts as an illustration to his theory.

In this study, Virno focuses on the post-Fordist economy, analyzing contemporary production models from philosophical, ethical, and epistemological perspectives and as a result offers the reader a comprehensive picture of “contemporary forms of life.” The main one among these forms is “the multitude” — a type of community and a revolutionary subject he distinguished from the people, crowd, or mass. “The multitude is a mode of being, the prevalent mode of being today: but, like all modes of being, it is ambivalent, or, we might say, it contains within itself both loss and salvation, acquiescence and conflict, servility and freedom.”

Virno studies different aspects of multitude: chapter one (or “day one”) is dedicated to the state of total anguish; chapter two looks into the conditions of labor, which has become abstract, and, apart from the necessary skills, demands new forms of relations and communication. The worker’s labor and, moreover, their “ability to speak,” is alienated in this situation. Discussing other aspects of the multitude (general intellect, emotionality, individuality, idle talk, curiosity, nihilism and escapism), Virno points out their ambivalent nature. On the one hand, the feeling of homelessness and anguish and rejection of politics create an individual unable to act. On the other hand, the same factors create conditions for resistance. In this respect, A Grammar of the Multitude is not only key to understanding contemporary leaderless protest movements (Occupy, We are the 99%, Russian protests of late 2011) and the current models of production (including cultural), but also a kind of a textbook on what a person, collective, and society in general can do. Only by understanding the ambivalence of one’s position can one make the right choice and opt for freedom, self-organization and solidarity. E. I.

Joshua Decter. Art Is a Problem

Zurich: JRP | Ringier, 2013. — 440 pp.

Joshua Decter is an acclaimed American curator, critic, and lecturer, who has organized ambitious exhibition projects at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Kunsthalle Wien, and the Santa Monica Museum of Art, and has collaborated with Bard College and New York University, among other institutions. This book, published in 2013, contains his theoretical articles, interviews with artists and curators, and his essays on particular artists, ranging from Michael Asher and Daniel Buren to Emily Jacir and the General Idea group. Focusing on the development of the art world from the late 1980s to the early 2010s, Decter points out that despite its success and the current cultural boom, contemporary art remains a problematic phenomenon. His critical review of contemporary art categories and practices opens with an extensive chapter on the problem of an arts museum, which (despite the popular idea of a white cube as of a sterile space) is never neutral, but is always a space of “disruptive and contradictory desires, believes and needs.” Revisiting the role of art criticism, Decter discusses its potential for social transformation beyond the production of specialist knowledge. He offers the reader a critique of the biennale culture and the changing function of art in contemporary urban spaces. V.L.

Drugoye iskusstvo. V 2-kh tt. [The Other Art. In two volumes]

M.: Khudozhestvennaya galereya “Moskovskaya kollektsiya,” SP Interbuk, 1991. — 340 + 234 pp.

The Other Art is a bible for anyone interested in Russian art of the postwar period. The two volumes, compiled by Leonid Talochkin and Irina Alpatova in 1991, remain the main source on Russian contemporary art in its definitive period from 1956 to 1976. The first volume is devoted entirely to the chronicles of underground art: apartment exhibitions, semi-illegal jazz concerts, literary battles between opportunistic pro-state writers and underground poets, political drama and social catastrophes. With no literary fluff or any kind of fiction, it reads like a nouveau roman and sticks to the very essence of contemporary art history. The second volume is the catalog for The Other Art. Moscow. 1956–1976—the first retrospective exhibition of Soviet underground art that opened at the State Tretyakov Gallery in 1990. This is a truly precious reference book on the era and those who made it what it was—an encyclopedia of names, things and events. In other words, the book is a good read as well as an important source for art historians. It is also essential reading for art dealers: the remarkable collector and archivist Leonid Talochkin describes all the artworks from the exhibition with his usual perfectionism. Along with the A-YA underground art revue, The Other Art is among the most informative and insightful sources on the time. A revised and expanded edition of volume one was published in 2005. However, as what is left in it is only the chronicle, the second edition lacks the smoothness and cohesion of the first one, in which history was presented in conjunction with art. Authors of the original edition invented a perfect combination of a chronicle and a detailed catalog, offering a broad cultural and historical perspective on the era. S. O.

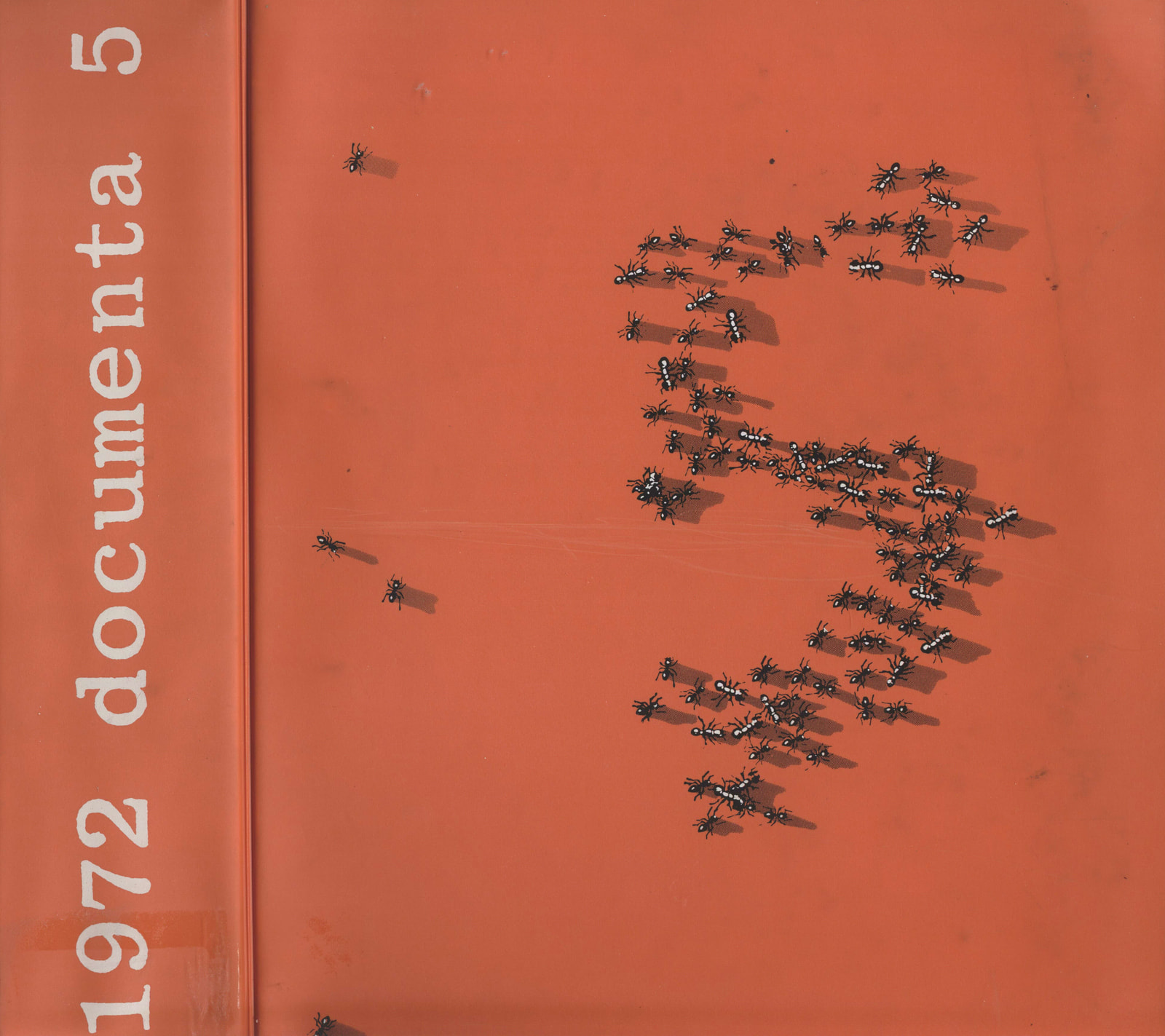

Documenta 5

Kassel: Paul Dierichs, 1972 (pages vary)

The Documenta 5 catalog is an orange vinyl D-ring binder with number “5” made of drawn ants on its cover. This edition is radically different from all previous Documenta catalogs, conventional biennale-type editions with introductory articles and glossy annotated illustrations.

The structure of this edition replicates the structure of the 1972 exhibition Questioning Reality—Image World Today (Befragung der Realität – Bildwelten heute) curated by Harald Szeemann. Instead of modernism and abstraction, which dominated the previous Documentas, this one presented “a concentrated version of life in the form of exhibition.”

The catalog can indeed be seen as an encyclopedia of Western European art after 1968. The first volume opens with Critical Theory of an Aesthetic Sign, a manifesto article by German philosopher Hans Heinz Holz—the author of the seminal From the Work of Art to a Commodity: The Function of an Aesthetic Object in Late Capitalism published the same year. The chapter Information features two important documents of the time: the infamous questionnaire made by Hans Haacke for his Visitors' Profile action, and The Artist's Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement co-authored by art dealer Seth Siegelaub and Bob Projansky.

Like Szeemann’s other projects, Documenta was widely criticized. At Garage Library you can also find a magazine by the radical left student group Rote Liste Kassel, which mocks Ed Ruscha’s work: the ants, which made the “5” on the catalog cover, have been dispersed by insecticide, which must be symbolizing the left’s critique of the exhibition, as exemplified by this edition. N.T.

Dmitri Prigov. Tolko moya yaponiya (nepridumannoe). [My Private Japan (A True Story)]

M.: Novoye Literaturnoye Obozreniye, 2011. – 320 pp.

So, which pronunciation is more accurate: “sushi” or “susi”?

Dmitri Prigov, or Domitori Porigov, as they call him in Japanese documents, was the first artist of his circle to visit the distant and mysterious land of Japan, and he describes what he found there in this travelogue. It’s easy to be the first one: you write whatever you want, and whatever you write will be true. Obviously, with Prigov’s talent and wit, this could not be a straightforward collection of facts about Japan, and although Prigov himself claims to have written “A True Story,” the reader does not really expect all of it to be true. Still, this book is a much more valuable companion than a standard travel guide listing the standard places to see, the hotels and the prices of food. The reader really gets a chance to see the country with the artist’s eyes. Prigov’s story is funny and at times absurd or shocking, but also very informative, and should be read and possibly reread several times by anyone going to Japan. Prigov does also touch on all the questions that you expect to be answered in a book on Japan, discussing sumo, Japanese cuisine, art, geishas and the Japanese mentality.

P.S. The correct pronunciation is actually “sus-shi.” It is not exactly what they say in Japan, but sounds the closest to the original—at least, that is what they told Prigov. A.T.