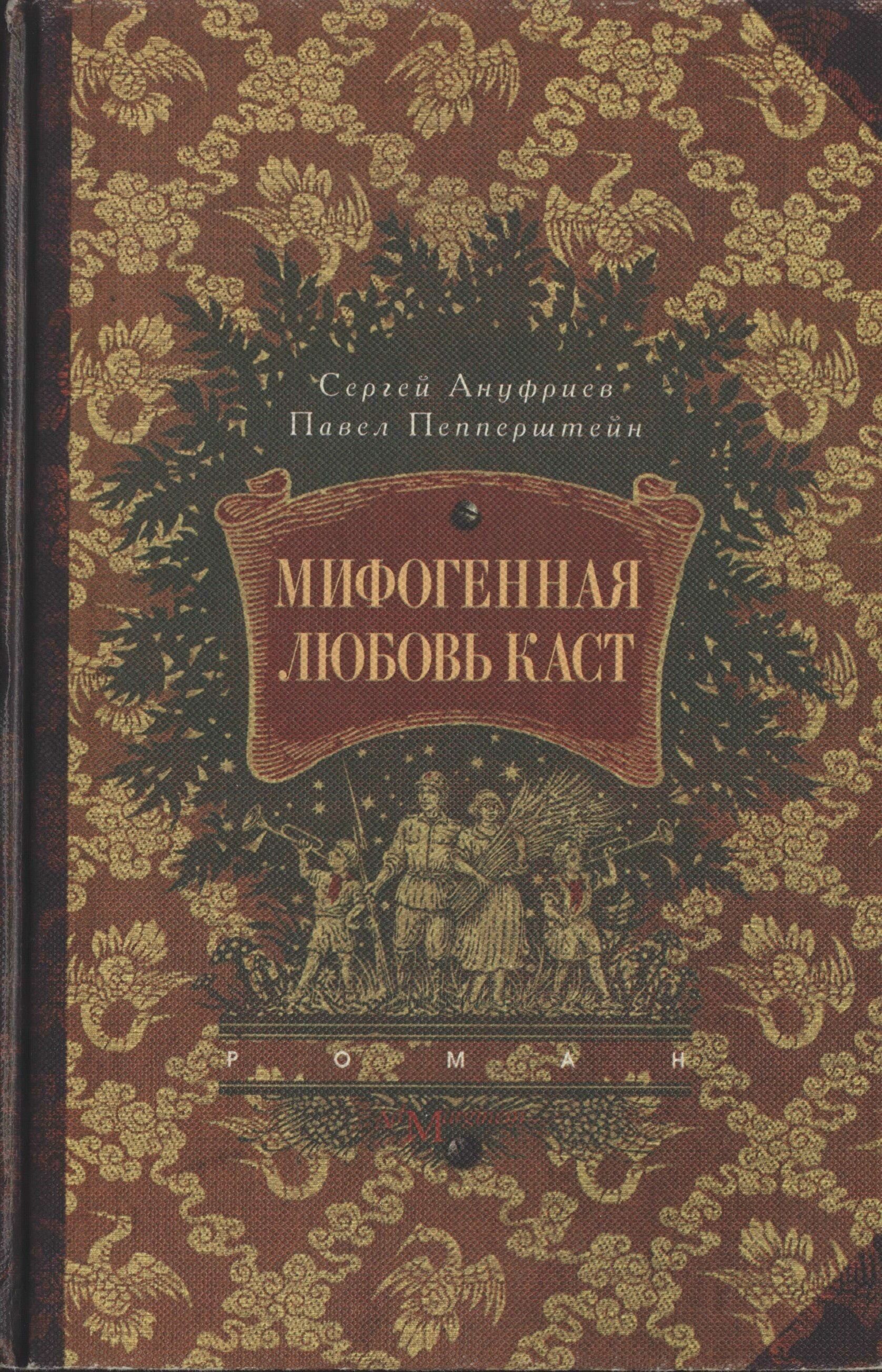

Sergei Anufriyev, Pavel Pepperstein. Mifogennaya lyubov kast [Mythogenic Love of Castes].

Moscow, Ad Marginem Press, 1999. — 478 pp.

Pavel Pepperstein. Mifogennaya lyubov kast. Tom 2. [Mythogenic Love of Castes. Volume 2]

Moscow, Ad Marginem Press, 2002. — 539 pp.

Strangely, the main postmodernist account of World War II was written by two artists of the younger generation of Moscow Conceptualists: Pavel Pepperstein and Sergei Anufriyev. The two-volume Mifogennaya lyubov kast is an example of psychedelic realism, where the protagonist of the delirious narrative is party functionary Vladimir Dunayev, who dies early in the war only to return to the front as a spirit. His battleground is a parallel reality where he is confronted by fairy tale creatures: the little boy and Karlsson, the Blue Fairy of a Killing House, Holy Girls, and other half-mythical creatures. Helping him are traditional characters from Russian folklore: the Chicken-Legged Hut, the Buzzy-Wuzzy Fly, the Magic Tablecloth, the Clergy, the Lieutenant, and a dozen others.

Their battles take place in the complex world constructed out of what we might call “inappropriate language.” The psychedelic realism of Mifogennaya lyubov kast is created out of fragments of borderline speech, where Russian folk tales get mixed with Vertinsky’s songs, Dunayev’s erotic hallucinations, excerpts from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, prison talk and rude rhymes, fables, Vassily Bykov-style Soviet realism, and Sorokin’s conceptualism.

Here Soviet culture meets folklore, and a party functionary becomes a shaman in the world that exists beyond history. However, the story is not so much about Dunayev as about language, evolving and unstable, defiantly rich in layers and meanings—the special language that only conceptual artists could tame. The fascist strategy is literally standing on eggshells, the Magic Tablecloth covers the battlefield, the dome of a church turns out to be a stinking onion, and the heads and tails of German eagles turn into coins. The language is an independent character as well as the general background and the driving force behind the story. Everything exists in language and is informed by it. This fixation on language materializes in the image of Mifogennaya lyubov kast—a hallucinatory definition of the war going on, as well as the book Dunayev discovers in the museum of the Don River hidden in one of the folds of his higher reality. This book is a catalogue of the museum, which is in its turn devoted to the events that are described in Pepperstein and Anufriyev’s book.

Apart from allusions to world literature (going back as far as Homer), the two volumes abound in references to the conceptualist circle. The character of Senya Headache, whom the reader meets in the chapter Odessa (volume 1), is a combination of conceptualist artist Senya Narrow Eyes and his band Boli [the aches] with Georgy Litichevsky and Farid Bogdalov. The Black Elsa — a deadly machine made of washboards that appears in the first pages of the second volume — is one of the most famous works by Yuri Leiderman. In the end, Pepperstein himself makes an appearance: as Murzilka the correspondent hits the keys, the letters emerge, that smell of “pepper and stone” (“Pepper und Stein”). E.I.