The exhibition Co–thinkers, currently on show at Garage, was developed in collaboration with a team of four regular visitors with different disabilities, and seeks to expand our understanding of inclusion beyond the notion of physical accessibility. Garage Research, together with inclusive programs manager and one of the exhibition’s curators Maria Sarycheva, have prepared an overview of publications available in Garage Library, which explore how art is perceived by groups that are often excluded as museum audiences.

Overview of publications for the exhibition Co–thinkers

Overview by Ilmira Bolotyan, Elena Ishenko, Maria Sarycheva and Anastasia Tishunina

Elena Zdravomyslova. Anna Tyomkina. 12 lektsiy po gendernoy sotsiologii [Nine Lectures in Sociology of Gender].

Saint Petersburg: European University in Saint Petersburg, 2015. — 768 pp.

Along with an introduction to the sociology of gender, its history and uses, the course of lectures by Elena Zdravomyslova and Anna Tyomkina touches on the theoretical basis of this branch of sociology, and its methodology. A separate chapter is devoted to intersectional analysis—or intersectional theory, which owes its name to the branch’s central metaphor of an intersection of social categories and identities. The theory suggests that identities are shaped by gender as well as other categories, such as race, class, ethnicity and ability.

Intersectional analysis seeks to examine the complex patterns of power distribution. Gender inequality is no longer seen as a dichotomy between male and female. Instead, men and women are envisaged as actors that also represent a particular class, race and multiple other groups. An academic discipline, intersectional analysis is also a political project aimed at a more just social order that would give marginalized groups access to vital resources. In intersectional analysis, ability is a factor as important as gender, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion etc. Each study focuses on several factors.

The constant addition of new factors to the list has allowed Judith Butler to speak of the “etc. effect”. Indeed, listing the categories that shape identities and affect the distribution of power, scholars often end with “et cetera”, but what or who does this phrase refer to? According to Zdravomyslova and Tyomkina, any intersectional analysis should not only look into universal factors, but it must also take into account the local context and the differences specific for a particular group. I.B.

Jacques Rancière. The Emancipated Spectator.

London: Verso, 2011. — 134 pp.

In this essential study on the problem of spectatorship in art, Jacques Rancière revisits the traditional understanding of observation and perception as passive consumption. This tradition envisages the viewer as a passive and ignorant spectator—essentially a consumer—while the artist or the author is seen as an active and knowing person. Rancière offers a different perspective on spectatorship, inviting the reader to think of it as of any other kind of human activity, which involves choosing, comparing, drawing connections—in other words, analyzing and interpreting what one is seeing or perceiving. “Spectators see, feel and understand something in as much as they compose their own poem, as, in their way, do actors or playwrights, directors, dancers or performers”, Rancière concludes.

Recognizing this fact, the French philosopher continues, is the first step to emancipating the spectator. Reaffirming the spectator’s ability to make a judgment about the work of art, Rancière proceeds to discuss the relation between the individual spectator and the audience, and the possibility of collective perception. According to him, it is precisely the spectator’s ability to develop individual interpretations based on individual experiences and beliefs that conditions the possibility of a collective experience of art, which he associates with the “distribution of the sensible”, and which, he believes, creates solidarity.

Emancipating the spectator essentially means providing him or her with independence of perception. Although he does not speak of that directly, by making the spectator active Rancière affirms the possibility of differences in perception (including beyond the core senses like sight and hearing) resulting from the human ability to understand and interpret a work of art. This leaves the artist or author responsible for allowing the freedom of interpretation by avoiding suggesting straightforward answers and solutions. E.I.

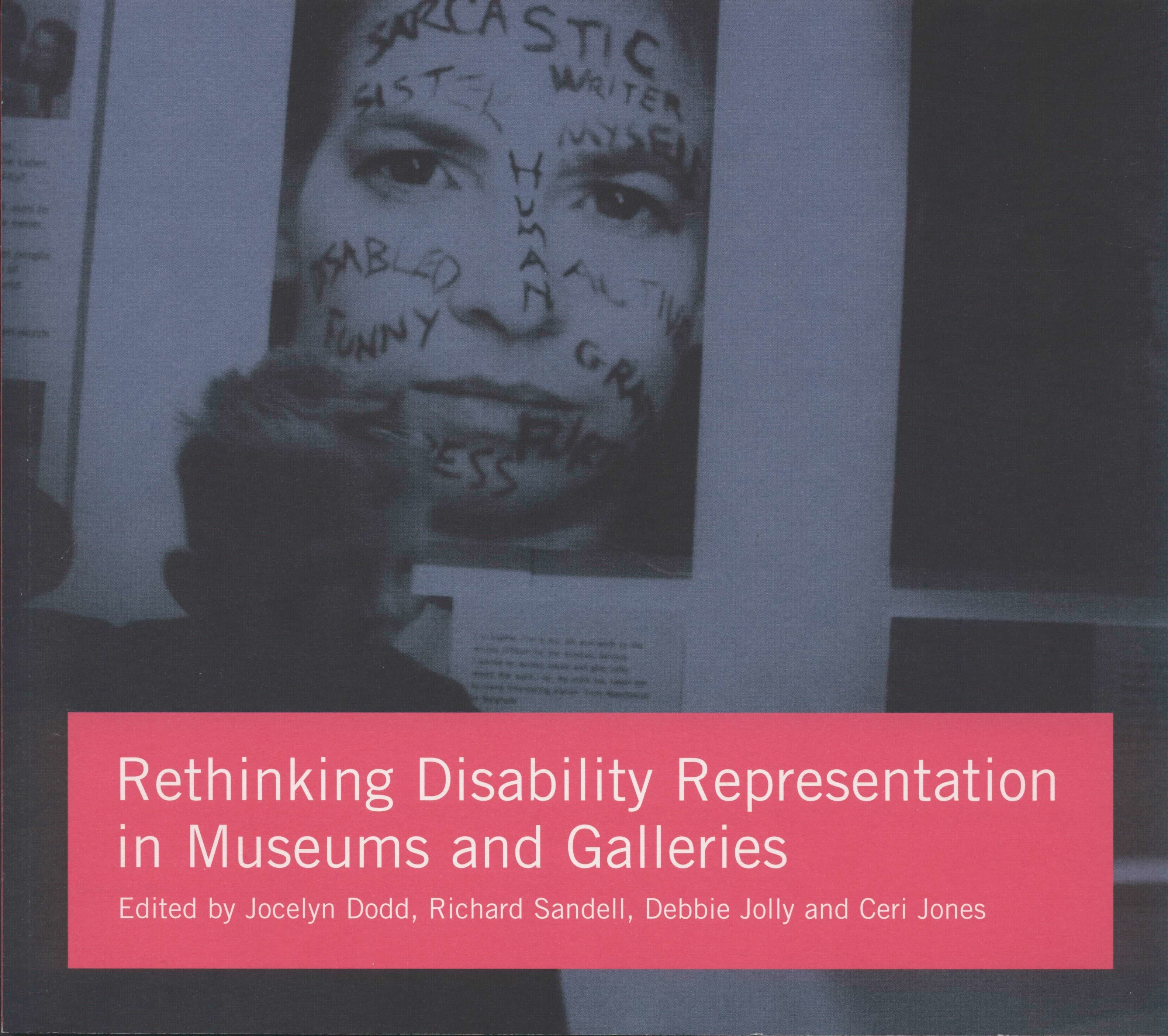

Rethinking Disability Representation in Museums and Galleries. Edited by Jocelyn Dodd, Richard Sandell, Debbie Jolly and Ceri Jones.

Leicester: RCMG, University of Leicester, 2008. — 169 pp.

The book is based on a 2007 study initiated by the Research Centre for Museums and Galleries (RCMG) at the University of Leicester, which examined the representation of disabled people’s lives and experiences in nine museums in the UK. As its starting point, the project had to shift the focus of disability studies from disability itself to the social and communication barriers disabled people face in their daily life.

Four sections of the book— Perspectives on Disability Representation, Museum Experiments, Reflections on Practice and Visitor Responses—correspond to the four stages of the research project. The project was developed by a team of four people who co-edited the report: Jocelyn Dodd, the head of RCMG who has initiated a number of similar studies; Richard Sandell, a lecturer at the University of Leicester, whose research focuses on the social role of contemporary museums and their ability to offer a critique of their own legacy; Debbie Jolie a human rights activist and sociologist, who studies the history of disabled people’s struggle for equality; and Ceri Jones, Professor of Psychology at the University of Leicester, whose academic research revolves around group dynamics. The team also collaborated with a number of activists, artists and art professionals with different disabilities, who also consulted the nine partner museums that have taken part in the project. Their collaboration has resulted in a number of exhibitions, screenings, tours and education events. For example, Glasgow Museum of Transport organized the exhibition Lives in Motion which included Protest Movement a poster calling for the end of discrimination against disabled people on public transport. M.S.

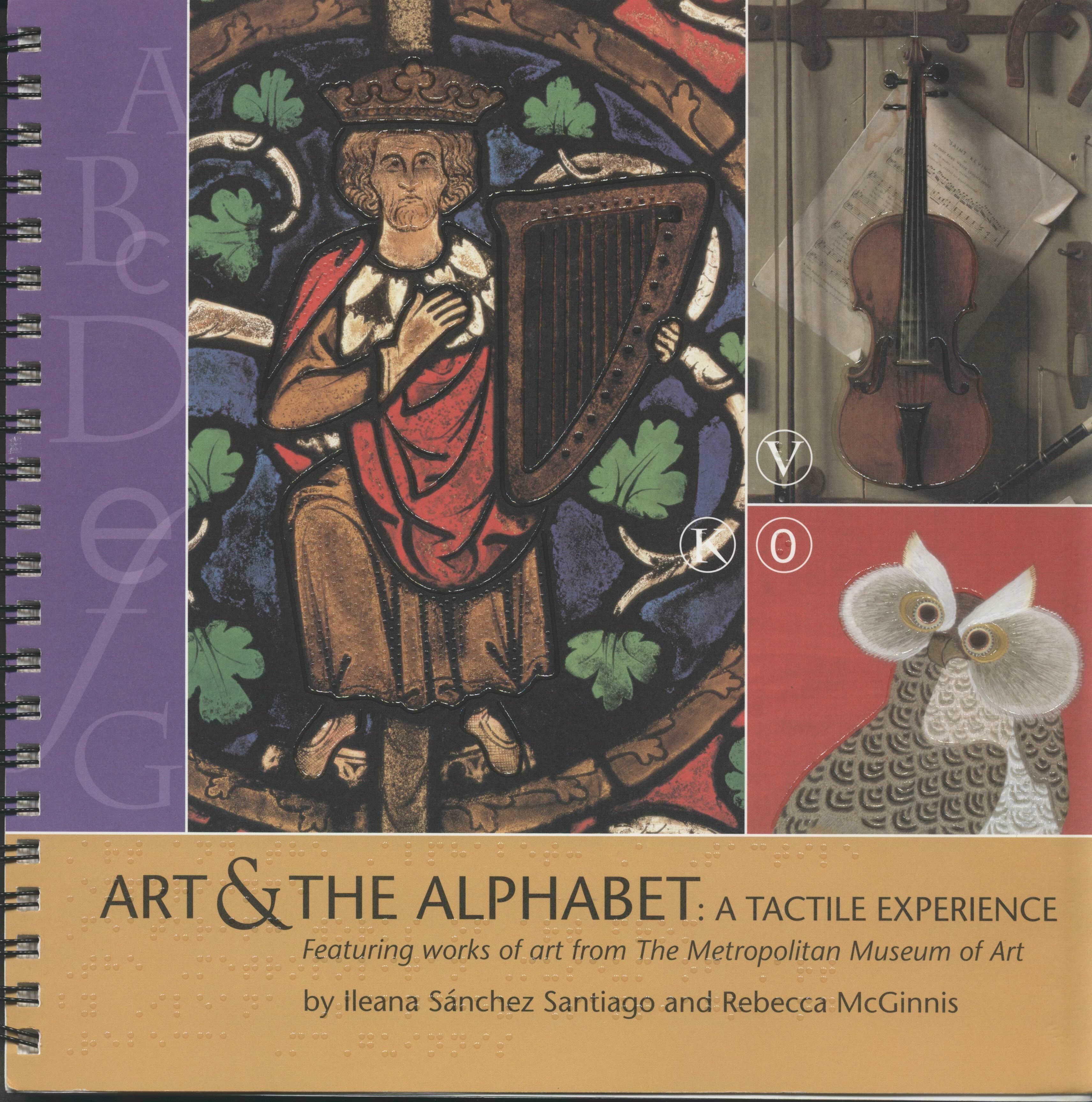

Ileana Sanchez Santiago, Rebecca McGinnis. Art and the Alphabet: a Tactile Experience. Featuring works of art from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009. — 35 pp.

Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is among the world leaders in adapting museum programs for visually impaired visitors. Tours for partially sighted and blind visitors usually involve audio description of exhibits and tactile exploration of their models. This combination allows the visitors to get an idea of the theme, composition, and scale of the work. In 2009, the Met published a tactile catalogue—an alphabet with tactile pictures of masterpieces from the Met’s collection. A is an angel from a 1180 Spanish manuscript; F is number five from Charles Demuth’s Figure 5 in Gold; P stands for the parrot from Woman with Parrot by Edouard Manet. The book also features recommendations on how to describe artworks for seeing readers, encouraging them not to shy away from talking about colours and using simple analogies. The alphabet was developed for children with visual impairments but will be useful to anyone interested in inclusion in art. M.S.

Sophie Calle. Blind.

Arles: Actes Sud, 2011. — 107 pp.

This album was made by the French artist Sophie Calle in collaboration with a large group of blind people she worked with over several decades. The project— exploring the way people blind from birth experience beauty—dates back to 1986. The first section of the book features photographs of all contributors to the project and their words are published in English and Braille–complete with illustrations. Participants speak of the beauty of nature and the beauty of colors, and touch on physical beauty and sexuality. While many find beauty in the human body, one female participant comments on the beauty of a particular sculpture by Rodin that she has explored through a tactile model. The section ends with a harsh quote from one of the male contributors “Beauty – I’ve buried beauty. I don’t need beauty; I don’t need images in my brain. Since I cannot appreciate beauty, I have always run away from it.”

The second section is devoted to the second part of the project, entitled Blind Color, which the artist started in 1991. For this part, Sophie Calle asked blind people what they saw and compared their answers with quotes on monochrome paintings from Malevich, Manzoni, Rauschenberg, and Richter. The third and final section of the book sums up Calle’s 2010 project The Last Image. “I went to Istanbul. I spoke to blind people, most of whom had lost their sight suddenly”, the artist recalls. “I asked them to describe the last thing they saw.” This is also the most dramatic part of the book as most of the memories are of traumatic experiences.

Providing an insight into how blind people experience the world for those of us who can see, the book is also a unique artist’s research project exploring how the imagined can turn into images. Each section documents Calle’s attempts to convey to the viewer the images and visual experiences of the blind. Together they create a kind of anthology on collaborations between an artist and blind people. A.T.