In December, Garage library celebrates two years since it first opened its doors to the public. In this overview, prepared for the anniversary, Garage Research talk about their favourite books among the recent acquisitions.

New Acquisitions: Staff Picks

Overview by Ilmira Bolotyan, Elena Ishenko, Maryana Karysheva, Valery Ledenev and Anastasia Tishunina

Tänd mörkret! Svensk konst 1975–1985

Copenhagen: Norhaven Paperbacks, 2007. — 185 pp.

This publication was prepared in conjunction with the second part of the exhibition project that started in 1998 with the show Hjärtat sitter till vänster (The Heart Is on the Left), devoted to Swedish contemporary art of 1964–1974. Artists and curators Ola Åstrand Ulf Kihlander point out that the decade that followed was just as fruitful in terms of art. ‘Besides,’ the add, ‘we wanted to rectify some omissions in the first exhibition, such as the total absence of the music.’

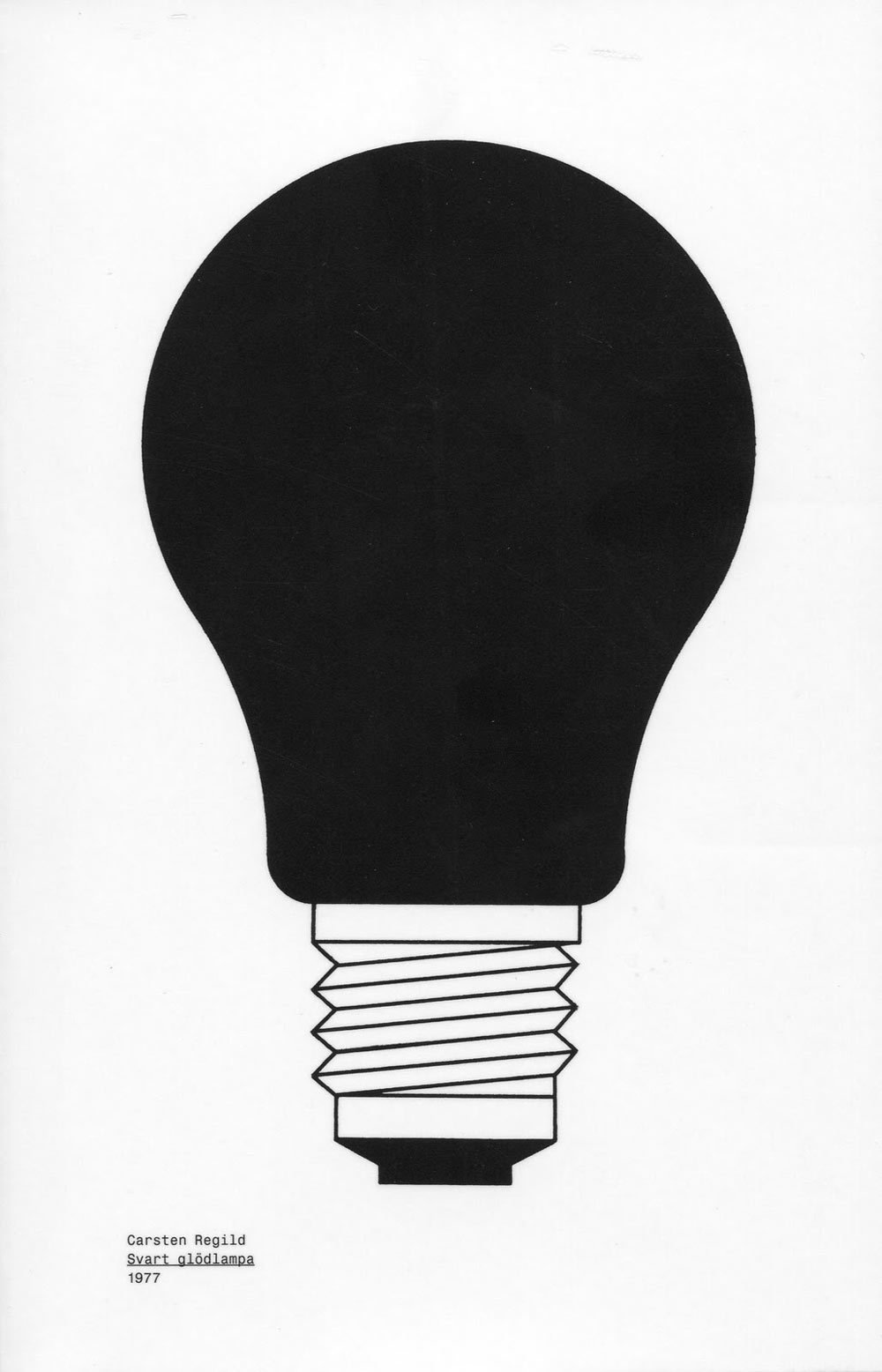

In the catalogue for the new show, an entire chapter is devoted to Swedish punk. In fact, the name of the exhibition—Tänd mörkret (‘lighten the dark’)—is a punk slogan coined in 1976, and which resonates with Black Lamp (Svart glödlampa), the work by Carsten Regild featured on the cover of the catalogue.

However, the history of punk is only one of the broad range of cultural and political phenomena of the decade covered in the recollections, interviews and articles included in the catalogue. Another chapter offers an overview of feminist art and the first exhibitions of Swedish female artists in Gothenburg. A special focus is made on performance art as one of the most dynamic art forms of the period.

Despite the fact that the Swedish art scene does not get much publicity internationally, it has produced a number of interesting artists, such as Erland Cullberg, Leif Elggren, Vesuvius poetry collective and Kjartan Slettemark, who turned himself into a dog twenty years before Oleg Kulik. Many of them are discussed in this book. A.T.

Dan Perjovschi. Auto Drawings

Göppingen: Kunsthalle Göppingen, 2003. — 48 pp.

The catalogue of drawings by the Romanian artist Dan Perjovschi was donated to Garage Library by Viktor Misiano. The publication features works that were exhibited in Kunsthalle Göppingen in 2003. Perjovschi’s witty minimalist drawings resemble illustrations or cartoons. The artist is most famous for his sharp comments on the contemporary globalized art world, but the drawings included in the catalogue seem more moderate than those of the past few years. The catalogue contains an analysis of Perjovschi’s works by Werner Meyer, and a brief account of dissident art in 1980s Romania, where Perjovschi’s artistic career began. V.L.

Сьюзен Сонтаг. Болезнь как метафора [Susan Sontag. Illness as Metaphor]

М.: Ад Маргинем Пресс, 2016. — 176 с.

Susan Sontag seems to have created a new genre of philosophical essay, where she distils various phenomena of our life to discover their pure essence. This is what she does to deadly diseases—tuberculosis, cancer and AIDS—in two essays—Illness as Metaphor (1978) and AIDS and Its Metaphors (1989)—published in Russian by Garage and Ad Marginem Press.

The main ambition behind Sontag’s analysis of popular and literary myths around diseases is to clear illness from the prejudice that surrounds it. Diagnosed with cancer, Sontag knew all too well that each person carries ‘two passports: one for the kingdom of the well, and one for the kingdom of the unwell’, and that settling in the latter, one invariably ends up entangled in a heavy bundle of metaphors.

Offering a comparative analysis of cultural perspectives on tuberculosis and cancer, Sontag’s essay is an appeal against giving diseases a moral aspect. Myths and metaphors that emerge around a disease, she argues, are a way of shaming their victims. Patients are made to believe that, consciously or not, they have brought the illness upon themselves, and therefore, they deserve it.

The second essay, contrasting cancer to AIDS, analyses the rhetoric around the latter. In the case of AIDS, the public shaming associated with other diseases is replaced with blaming, as ‘everybody knows’ who has the highest chances of getting it. The rhetoric of blaming the ill, Sontag points out, has been used by politicians, who spoke of disease as a punishment for homosexuals, migrants and, generally, the Other. By labeling AIDS as a ‘homosexual plague’ societies used the real disease as an excuse for discrimination.

Although apocalyptic fears have become a common phenomenon, Susan Sontag concludes by expressing a hope that one day AIDS will become nothing but a curable illness, and will not come with the burden of metaphors and myths that surround it today. I. B.

Алексей Юрчак. Это было навсегда, пока не закончилось. Последнее советское поколение. [Alexei Yurchak. Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation]

М.: Новое литературное обозрение, 2014. — 664 с.

In his main work to date, Berkeley professor Alexei Yurchak focuses on what he calls the last Soviet generation—people born in the 1950s and 1960s—and the internal factors behind the collapse of the Soviet regime. As the starting point for his narrative, Yurchak chose the death of Stalin: the disappearance of a powerful figure that led to a dramatic shift in the life of society and the loss of meaning behind the party’s rhetoric, which was, nevertheless, endlessly reproduced in society’s organization and daily routines—from Komsomol to elections—and thus acquired a new performative meaning. People’s presence at the party meetings no longer meant they were truly interested in whatever was discussed, but allowed them to appear ‘normal’. Spending a quarter of an hour on party matters, they were them free to proceed with their daily life.

Focusing on such ‘normal people’, Yurchak offers an alternative to binary oppositions common in studies of Soviet culture: conformism vs. non-conformism, official vs. unofficial culture, the Soviet vs. the anti-Soviet. Instead, Yurchak analyses Soviet life through the concept of ‘living vnye’ (derived from Bakhtin’s vnyenakhodimost’, which can be roughly translated as ‘outsiderness’): a way of life that was shared by underground artists and Komsomol functionaries, who endured the boredom of party meetings to have a new vinyl by The Beatles. The empty official discourse required no moral investment and was reduced to a comfortable background for any kind of activity—from studying abstract algebra and foreign languages to spending time in cafés and playing in a rock band.

Of special interest are the chapters devoted to the art practices of the time: Mitki and Necrorealism movements, Dmitri Prigov’s legacy and the Soviet folklore. E. I.

Говард Чапник. Правда не нуждается в союзниках. [Howard Chapnick. Truth Needs No Ally]

СПб.: Клаудберри, 2016. — 456 с.

Translated into Russian by Klaudberri in 2016, this fundamental study of the history of photography and photographic practice by the former head of the famous Black Star Photo Agency was first published in 1994. Offering some general guidance for aspiring photo journalists (from how to organize a portfolio to how to interact with clients and agencies), the book also discusses the basic questions of professional ethical code, including the concept of a ‘concerned photographer’ introduced by Cornell Capa. With chapters devoted to racial and gender discrimination in the profession, the book covers some of the key ethical problems in photojournalism, which have only been aggravated by digital technology.

Heavy with quotes from interviews and Chapnick’s private conversations with stars like Dorothea Lange, Cornell Capa, Eugene Smith and Donna Ferrato, Truth Needs No Ally is also an introduction to the history of photojournalism, and an overview of its achievements and failures.

In the preface to the Russian edition, Vladimir Dudchenko discusses the changes that have taken place in photojournalism since the book came out in 1994, including the further spread of accessible photo technology and the blurring of the border between photojournalism and art. M. K.