Garage’s first Triennial of Russian Contemporary Art features works by over 200 artists from forty Russian cities and towns. In this overview Garage Research presents a selection of books on contemporary art in Russian regions.

Books on Art in Russian Regions

Overview by Ilmira Bolotyan, Maryana Karysheva, Valery Ledenev, Maria Shmatko and Yury Yurkin

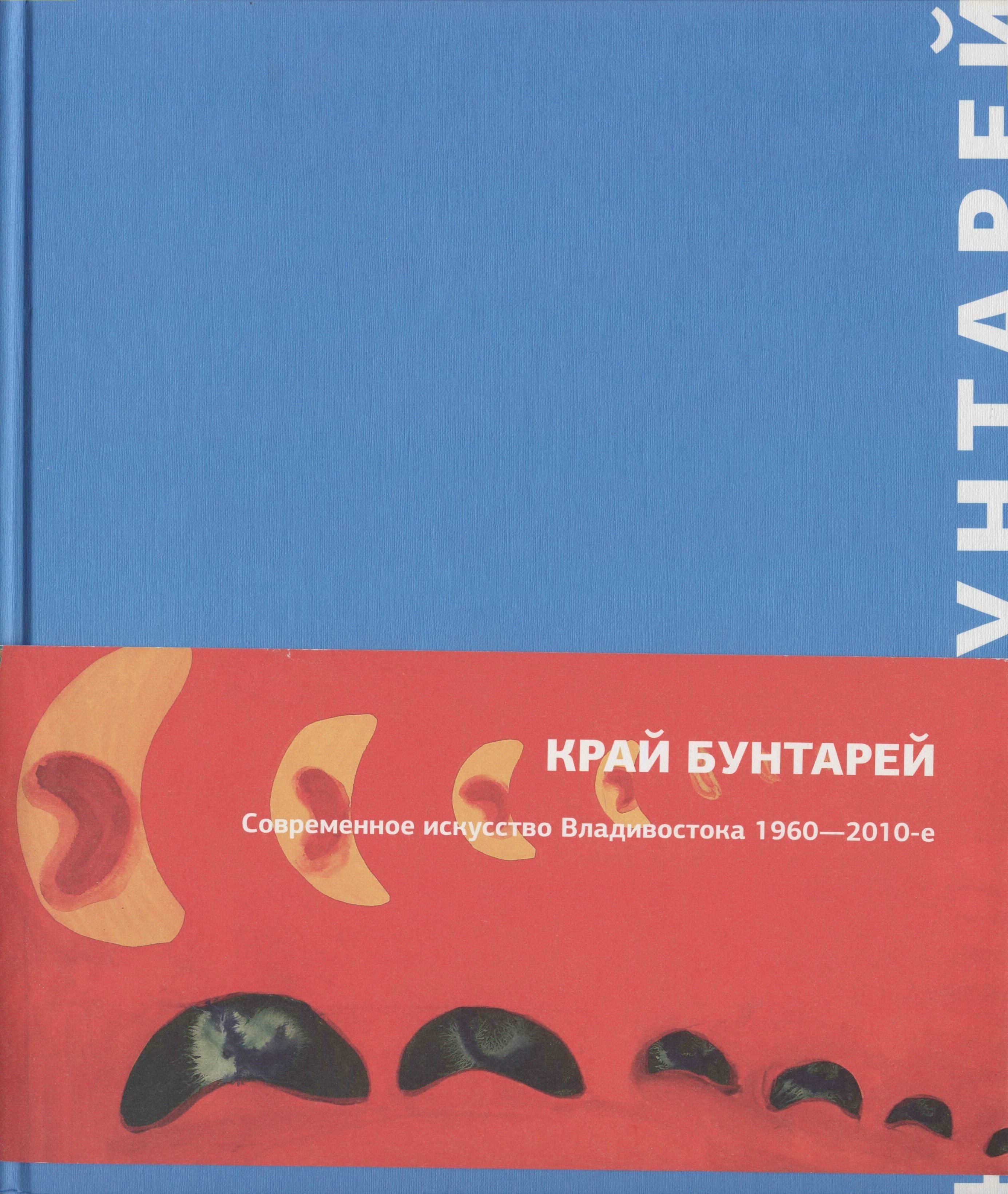

Край бунтарей. Современное искусство Владивостока 1960-2010-е. [The Land of Rebels. Contemporary Art in Vladivostok]

М.: Maier Publishing, 2016. — 144 с.

This catalogue was published in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name, which took place in Zarya Center for Contemporary Art in Vladivostok in 2015–2016. The exhibition featured works by twenty-three artists that are still little known outside Primorsky Krai.

In their review of the ‘underground’ art of the region, curators Alisa Bagdonayte and Vera Glazkova chose to focus on conceptualist works, inscribing them into the broader context of Russian contemporary art. The catalogue contains several articles, each offering a particular perspective on the projects included in the exhibition.

In her The 1960s and 1970s: Nonconformism or the Underground, historian Natalya Levdanskaya points out that due to the region’s location its cultural scene was secluded from what was going on in the rest of the country and lacked natural conditions for the emergence of a ‘different’ art. Despite certain similarities in their experimental practices, nonconformist artists of Primorsky Krai and Vladivostok failed to unite and organize any group exhibitions. Contemporary art in the region emerged with the formation of art groups like Vladivostok, Shtil, and Triada, and the opening of independent galleries such as Arka Gallery and Arteage. However, most artists were aiming to show their works in the neighboring countries—China, Korea and Japan—and often remained invisible within Russia.

Arseny Shteyner’s The Near Far East is a discussion of whether the current developments in contemporary art can be well described and understood at the moment they are happening, while Yulia Liderman’s Document of the Revolution (Curator’s Notes), on the contrary, outlines a possible methodology for such analysis through the reconstruction of contexts behind particular works.

Apart from the local ‘underground’ artists who already have a name, curators have selected works by several emerging artists including 33+1, Kirill Kryuchkov and Alexey Krutkin.

Introducing a number of new names, the catalogue is an important contribution to writing the history of contemporary art of the region. But the question of how an artwork can be relevant outside of the local context that produced it remains open. I. B.

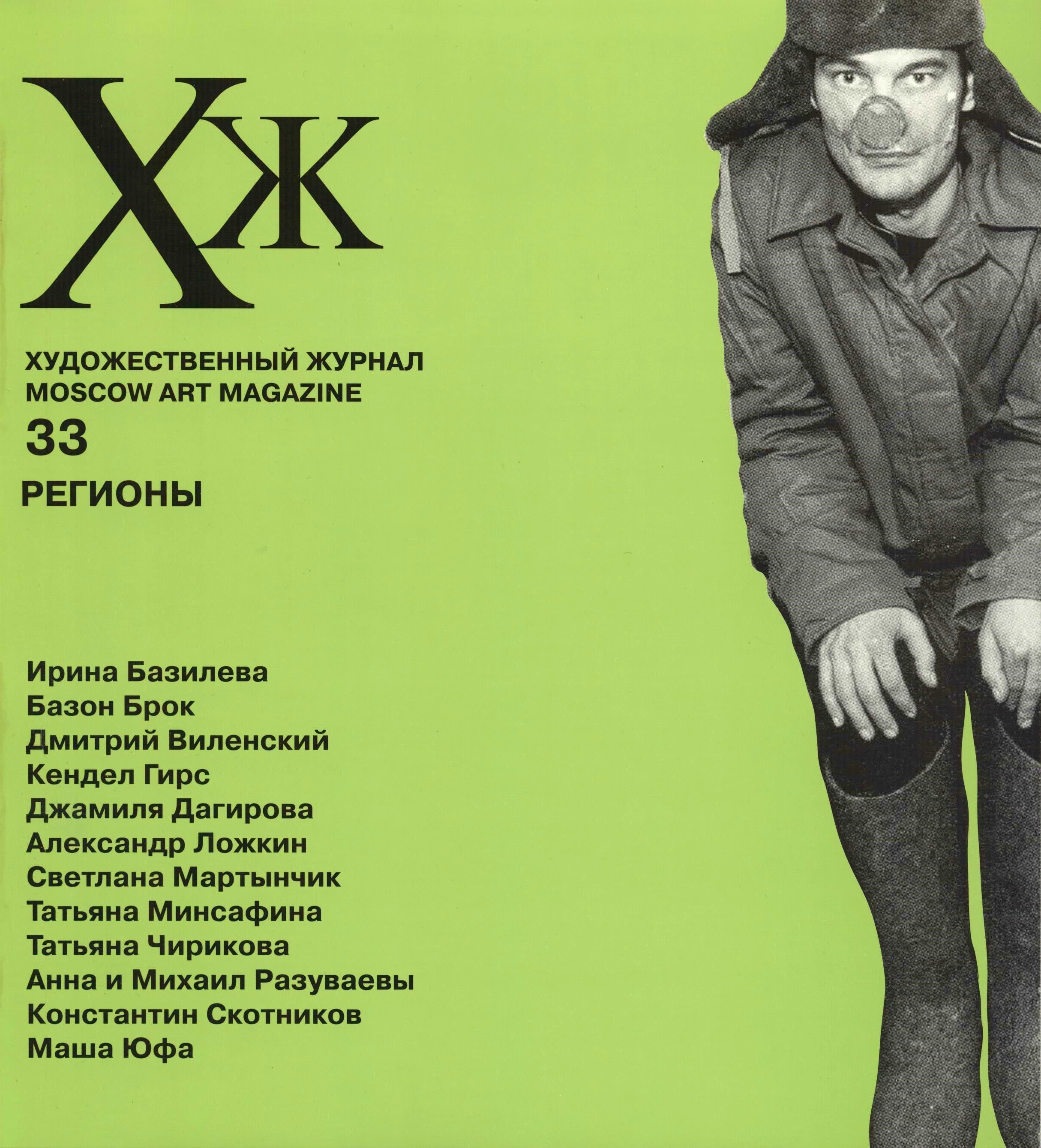

Художественный журнал. 2000. № 4 (33). Регионы [Moscow Art Magazine. 2000. No 4 (33) Regions]

In 2000, Moscow Art Magazine devoted an entire issue to a survey of contemporary art scenes in Russian regions. The magazine’s inquiry offered little hope: most cities discussed in the issue had no museums, galleries, critics or contemporary art education. Whatever happened in contemporary art was organised by artists themselves, with little or no help from local institutions. (Walking around Lake Onega. M. Yufa)

Artist Alexander Lozhkin begins his analysis of the art scene in his home city (Novosibirsk Zone) by saying that Novosibirsk ‘has two contemporary artists—maybe three’, and this description would be true of many Russian cities. Narrow as it was, at some point the circle of contemporary artists began to widen. Perhaps, it was the influence from the outside or the natural development of the community itself. Either way, the centripetal force has drawn quite a few local artists to Moscow. As Svetlana Martynchik writes in her Peculiarities of Provincial Pointlessness, “what kept the local artist alive is the myth of the capital city <…>, where people will be able to ‘understand’ him, ‘appreciate’ his work, and will surely want him to stay.” One city where the state of things has been different is Saint Petersburg, with its poor but cheerful bohemians creating their own artistic communities and contexts. “I suppose, Saint Petersburg is the last remaining zone of the ‘great chill’,” Dmitry Vilensky writes in The Art of Wasting.

On the other hand, Moscow, which might appear to be the mecca of contemporary art if one looks from the regions, remains at the periphery of the international art scene. The art world, as the world in general, is still in need of decentralization, Kendell Geers concludes in the first article of the issue. M. K.

Искусство против географии. [Art against Geography]

М.: ООО “Арт Гид”, 2011. – 64 с.

Russian curators and institutions have turned their eyes towards the regions before the Garage Triennial. One project involving artists from several Russian regions was organized by Marat Guelman as part of the 4th Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art (2011).

Art against Geography was produced by the Cultural Alliance, Guelman’s creation, which he defined as a non-commercial initiative to introduce Moscow to the art practices from the regions, represent regional artists and extend the Moscow art scene into the country. The name was later transferred to what was previously known as Marat Guelman Gallery in Moscow. The Gallery is no longer open, but many publications about it are available at Garage Library.

The 2011 exhibition featured works by artists from Saint Petersburg (Vladimir Kozin, Ekaterina Florenskaya), Perm (Mikhail Pavlyukevich and Olga Subbotina), Ufa (Timofey Dorofeev, Rinat Voligamsi), Yekaterinburg (Darya Zakharova, Evgenia Mikheeva and Tatyana Komova), Samara (Alisa Kot-Nikolayeva), Togliatti (Mikhail Lezin) and other cities, including those represented by other artists at the Garage Triennial.

Unlike the Triennial, Art against Geography reflected the perspective of one curator. Curiously, the project was an inverse of another exhibition of the same name, which took place at the Russian Museum in 2000 and was entirely devoted to the projects of Marat Guelman Gallery. The catalogue of that exhibition is also available at Garage Library. V. L.

Живая Пермь. Культурный текст. [Living Perm. The Text of Culture]

Пермь.: PERMM, 2012. — 299 с.

The publication is devoted to the ‘cultural revolution’ that happened in Perm between 2008 and 2013, and offers an overview of exhibitions, festivals, and reforms of the period. Although structurally it resembles an exhibition catalogue, essentially the book covers a much broader phenomenon—an experiment in creating in one of the smaller Russian cities an arts cluster similar to the one in Sheffield, UK.

Along with descriptions and photographs of exhibitions at the Perm Museum of Contemporary Art and of public art objects across the city, the book offers some general information about Perm’s cultural traditions and landmarks, from Stroganov icons, embroidery and bronzework, to Sergei Diaghilev and the city opera. Several articles look at successful local art initiatives, including a Soviet-era labour camp museum Perm-36 and Flahertiana Documentary Film Festival. A particularly valuable contribution to the book, Anna Suvorova’s Perm Underground tells the story of Non-Artists, the Friends of Postmodernism—a local group of activists visualizing contemporary philosophy in the early 1990s.

The book’s design and quality of print match the ambition of the cultural experiment that promised to put Perm among the key European cultural destinations. However, as you turn the last page, you are left with the question of what exactly constituted Perm’s cultural phenomenon—whether it was the ‘animal style’, Syava the rap musician, Teodor Currentzis, or the TV-series Real Guys. Yu. Yu.