In memory of Nikita Alexeev (1953–2021)

The exhibition explores the relatively small segment of contemporary art that is dedicated to investigating and challenging the durational dimension of its agents, from the body of the artist to the act of making and viewing art. It brings together works by 30 artists from different generations across Southeast and Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern and Western Europe.

The title in English, Spirit Labor, has been borrowed from the eponymous film essay by British curator and performance historian Adrian Heathfield, in which he traces a special kind of labor that transpires in artistic practices “inclined toward elemental exposure and non-human forces.” Spirit Labor, as artist Melati Suryodarmo has pointed out, is not about spirit itself but about the underlying principle behind the making and performing of some works that betrays a sustained practice of spirit. The Russian title of the exhibition, In Service to Time, offers a slightly different perspective, drawing our attention to the durational aspect of such practices; to the turbulent human dependence on the only truly non-renewable resource: time.

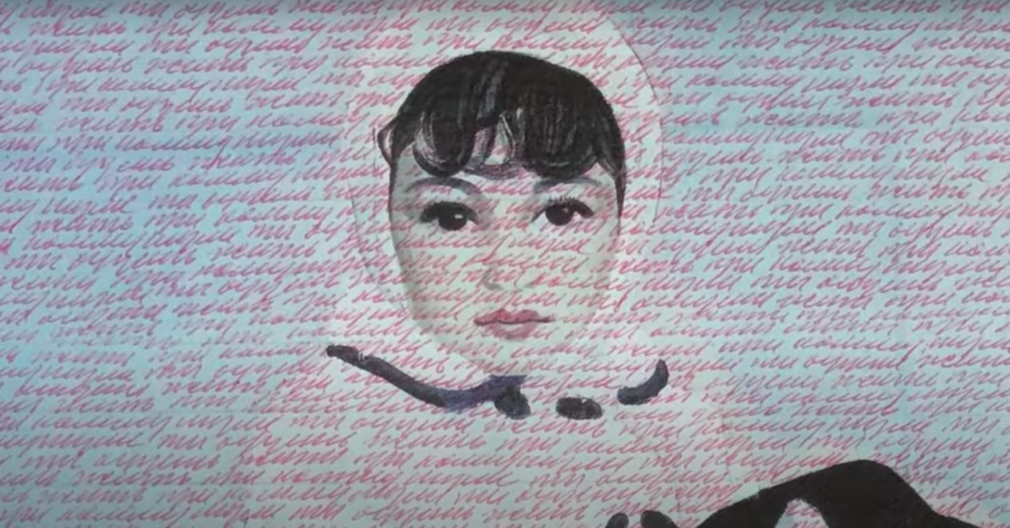

The focus on duration—on viscous, problematic, unhistorical time—often produces works that are hard to make and live through, such as those made gradually throughout the artist’s entire life. Tehching Hsieh produced only seven works in his lifetime, with each taking no less than a year to make and the longest and final piece completed over fourteen years. Vyacheslav-Yura Useinov spent eleven years making his small painting The Shadow of a Non-Existent House, explaining that the image on the canvas was the result of his spiritual and emotional effort, which allowed him to stoically keep that fading visual memory before his eyes at all times.

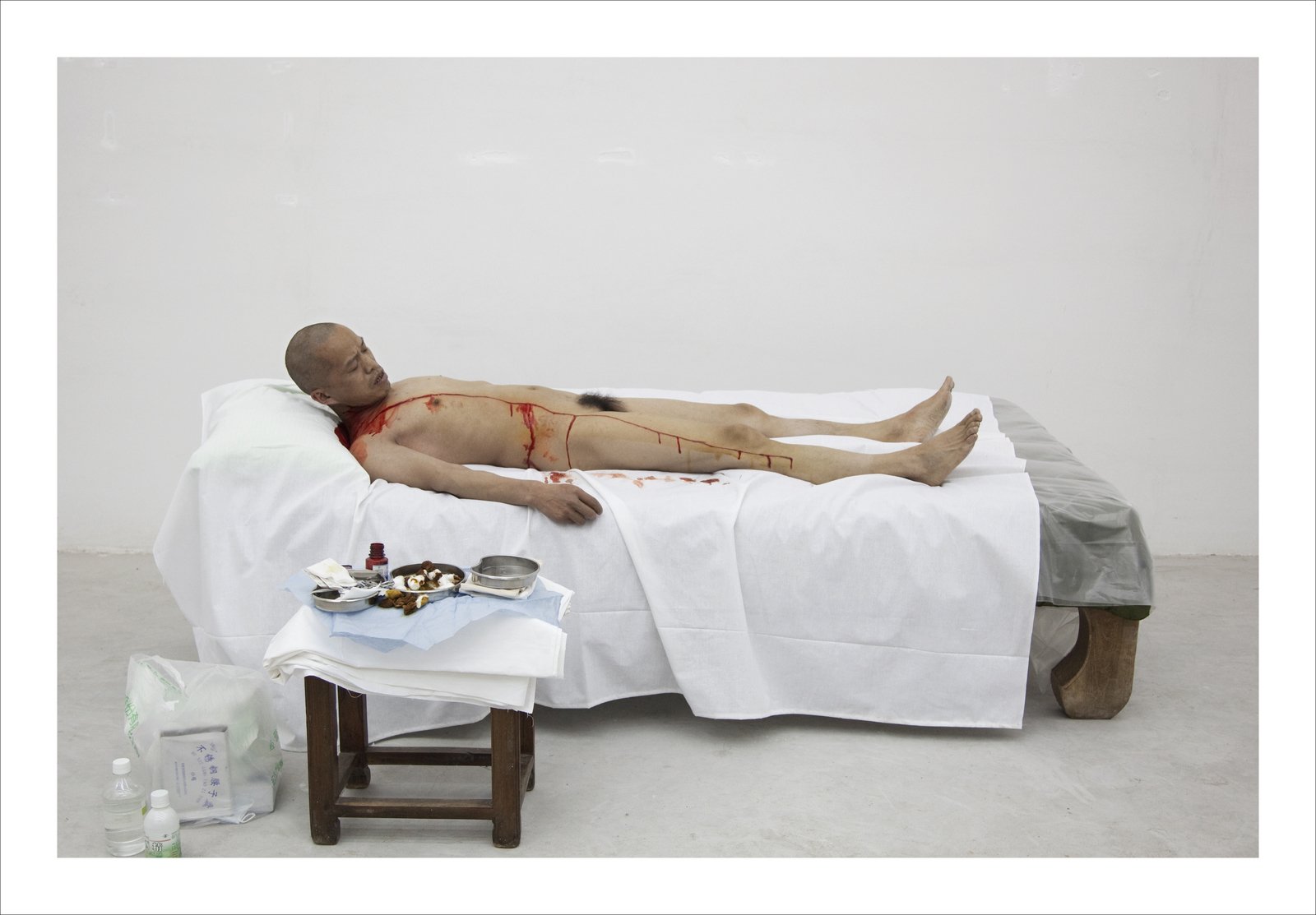

In exploring the many different aspects of what duration(al) can mean, from endurance and body art to conceptual practices, Spirit Labor touches on the inner psycho-emotional work of the artist, something that can lead to great effort and colossal difficulty, the overcoming of which often produces affect. In her performance Save My Soul, Elena Kovylina steered a rickety boat toward a storm and survived by a miracle. He Yunchang made a meter-long cut on his body as a gesture of resistance to non-democratic forces. Similarly, Yoshiko Shimada “became” a statue in front of the Japanese embassy in Korea as a reminder of the continuing taboo in Japanese society on discussing the fate of so-called “comfort women” (women who were sexually exploited by Japanese soldiers during World War II) and violence against women in Japan and worldwide even today. Fiete Stolte runs from time on an airplane, moving across time zones to get ahead of the light-day and gain an extra day of life.

The exhibition design, developed in collaboration with architects from Grace, encourages an almost “confessional” confinement with each artwork by placing them within separate cubicles made of concrete, the visual and technical properties of which were originally conceived to be very much “in service to time.”

This project was implemented with the support of Garage Endowment Fund.

18+

To confirm that you are an adult please present the original of your identity document.

Curated by Snejana Krasteva and Andrey Misiano